Healthcare was based on three pillars in 16th century Florence, Italy: diet, surgery, and pharmacy. Five centuries later, not much has changed in Italy or the U.S. But how healthcare gets funded and delivered in the context of these pillars significantly varies between the two countries, and impacts each nation’s health.

Healthcare was based on three pillars in 16th century Florence, Italy: diet, surgery, and pharmacy. Five centuries later, not much has changed in Italy or the U.S. But how healthcare gets funded and delivered in the context of these pillars significantly varies between the two countries, and impacts each nation’s health.

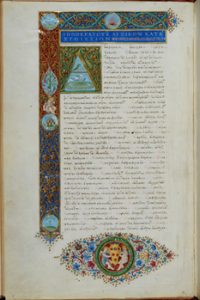

To put this in context, visiting the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (the Medici’s Laurentian Library) today  in Florence was a trip through medical-surgical history, starting in the second half of the 16th century. The design of this magnificent library’s foyer and reading room was initially conceived by Michelangelo. The reading room features 88 stalls of wooden reading

in Florence was a trip through medical-surgical history, starting in the second half of the 16th century. The design of this magnificent library’s foyer and reading room was initially conceived by Michelangelo. The reading room features 88 stalls of wooden reading  desks, seats and shelves. That room boasts stained glass windows with Medici crests and symbols.

desks, seats and shelves. That room boasts stained glass windows with Medici crests and symbols.

The Library’s book and manuscript collection spans the subjects of great minds from whence those minds committed big thoughts to paper. Discussions of astronomy, geography, philosophy, poetry, and rhetoric abound. Here, you can find the works of Cicero, Pliny, Seneca, DaVinci, Cellini and countless other brilliant minds.

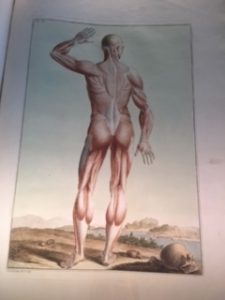

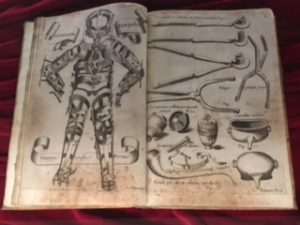

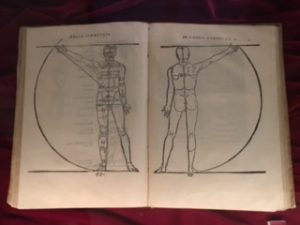

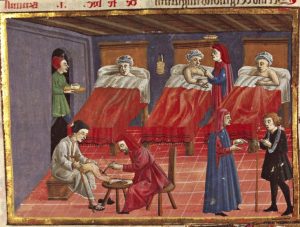

I was particularly keen to view the health, medical, and anatomical works in this treasure trove. The first three drawings shown here come from the Library’s collection that brought to mind the contemporary Grey’s Anatomy.

Three manuscripts among hundreds of examples represent the in-health-everything-old-is-new-again phenomenon. First, take the Corpus Hippocraticum scribed by Demetrius Damilus. This work includes the Hippocratic Oath that clinicians continue to vow today. Note that the content also contains De diaeta which provides a foundation for modern ideas about nutrition. The advice recommends that physical activity be considered as part of a healthy life- and eating style modulated by one’s physical condition and age. Remember: this advice was offered back in the mid-1500s.

Three manuscripts among hundreds of examples represent the in-health-everything-old-is-new-again phenomenon. First, take the Corpus Hippocraticum scribed by Demetrius Damilus. This work includes the Hippocratic Oath that clinicians continue to vow today. Note that the content also contains De diaeta which provides a foundation for modern ideas about nutrition. The advice recommends that physical activity be considered as part of a healthy life- and eating style modulated by one’s physical condition and age. Remember: this advice was offered back in the mid-1500s.

Before De diaeta there was a volume called Liber medicinalis Almansoris by a clinician called Rhazes. In this manuscript you find various medical topics including the impact of sleep on health, hygiene and bathing, advice on eating and drinking, and care of teeth and eyes.

Before De diaeta there was a volume called Liber medicinalis Almansoris by a clinician called Rhazes. In this manuscript you find various medical topics including the impact of sleep on health, hygiene and bathing, advice on eating and drinking, and care of teeth and eyes.

A third codex of interest is De peste by Antonio Benivieni, which emerged in the second half of the 15th century. In here, you learn about the role of living a joyful life to ward off the danger of infection. This was written during the great plague epidemics, and focused on hygiene and preventive medicine with a nod to mental health and employing the imagination, “to dispel thoughts of death, which depress and weaken the spirit.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Examining the healthcare section of a special exhibit at the Library, “Tesori Inesplorati,” which translates to “Unexplored Treasures,” organized various books and manuscripts by subject area. In the section on the human body and healthcare, we learned that the medical, surgical and pharmaceutical professions have flourished in Florence, which is a major capital of science learning, research and development in Italy. An historical nugget in the exhibit’s introduction was that the first license granted to a woman to practice surgery in Italy was issued in 1788. FYI, the first female physician in the United States was Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, who graduated from Geneva Medical College in 1849.

If you work in health care, it is useful to reflect on the 500-years that have passed since the calligrapher of the Corpus Hippocraticum put pen and ink to parchment. How much has really changed since the second half of the 16th century? So much: we are curing so many cancers, and this is one area where US patients have it better than health citizens living in other countries. While the OECD comparative data show that Americans rank low on many healthcare indices (such as mortality for adults and infants, self-rationing care due to costs, and obesity rates), outcomes for cancer treatment rank highest in the world.

But what of “diet, surgery and pharmacy,” and particularly “diet?” I wrote of the Blue Zones’ way of living while here in Italy, and the prospects for disease prevention and health promotion. I wrote, too, of pharmacy, and the self-care trends that health consumers increasingly embrace to improve health, gain empowerment and control, and lower personal healthcare costs.

So regarding “surgery,” what we-know-we-know is that surgery happens downstream, often years after a person has made lifestyle decisions that can increase risks to heart disease, orthopedic issues, and gut problems. Greater focus on the early part of living, and the risk-limiting social determinants of health, can help mitigate greater costs (and surgical interventions) later in life. Baking health into social policies helps improve healthcare finances and outcomes for people the world over.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.