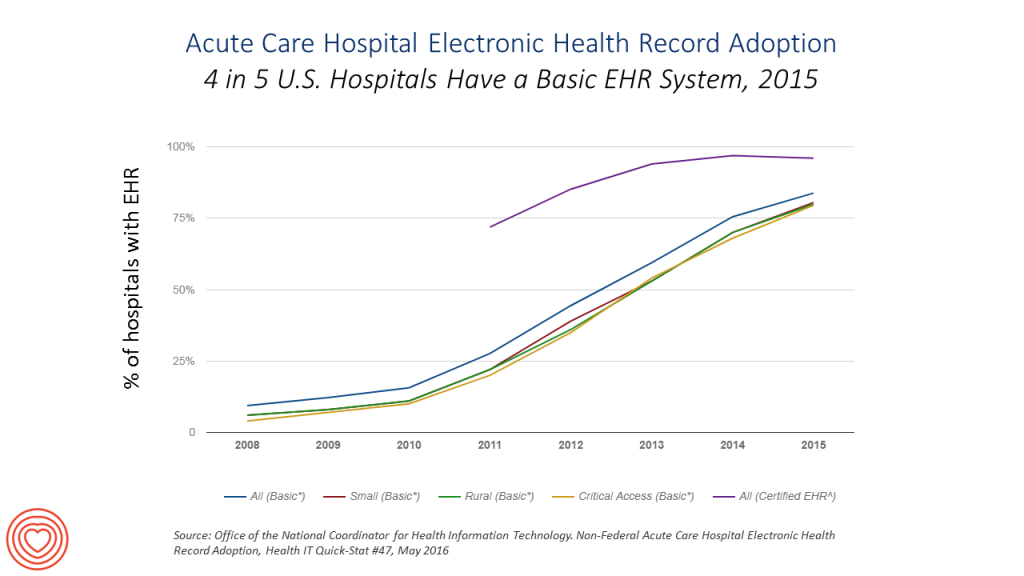

Most physician practices and hospitals in the U.S. have installed electronic health records (EHRs). But in a classic Field of Dreams scenario, we have made patients’ medical records digital, but people aren’t asking for them or accessing them en masse.

“How do we make it easier for patients to request and manage their own data?” asks a report from the Office of the National Coordinator of Health IT (ONC), Improving the Health Records Request Process for Patients – Highlights from User Experience Research.

The ONC has been responsible for implementing the HITECH Act’s provisions, ensuring that health care providers have met Meaningful Use criteria for implementing EHRs, and then receiving the financial incentives embedded in the Act for meeting those provisions.

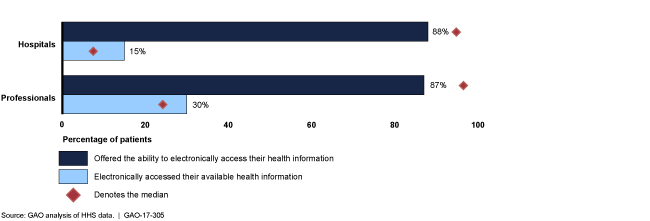

Now that the majority of health care providers in the U.S. have indeed purchased and implemented EHRs, it remains for patients, health consumers, and caregivers to take advantage of them. In my post on the EHR Field of Dreams effect, I highlighted research from the U.S. General Accountability Office that explored the question of how the Department of Health and Human Services should assess the effectiveness of efforts to enhance patient access to EHRs.

Now that the majority of health care providers in the U.S. have indeed purchased and implemented EHRs, it remains for patients, health consumers, and caregivers to take advantage of them. In my post on the EHR Field of Dreams effect, I highlighted research from the U.S. General Accountability Office that explored the question of how the Department of Health and Human Services should assess the effectiveness of efforts to enhance patient access to EHRs.

The ONC team conducted in-depth interviews with 17 patients to understand their health IT personae and personal workflows for accessing their personal medical records. The research also considered medical record release forms and information for 50 large U.S. health systems and hospitals, and interviewed “insiders” –health care stakeholders inside and outside of ONC — to assess how patients request access to medical records data and look for solutions to improve that process.

Why is it so important for people to access their medical records? By doing so, patients and caregivers can better manage and control their health and well-being, ONC notes, by preventing repeat tests, managing clinical numbers (like blood pressure for heart or glucose for diabetes), and sharing decision making with doctors and other clinicians — together, the process of patient and health engagement which boosts health outcomes for individuals and populations.

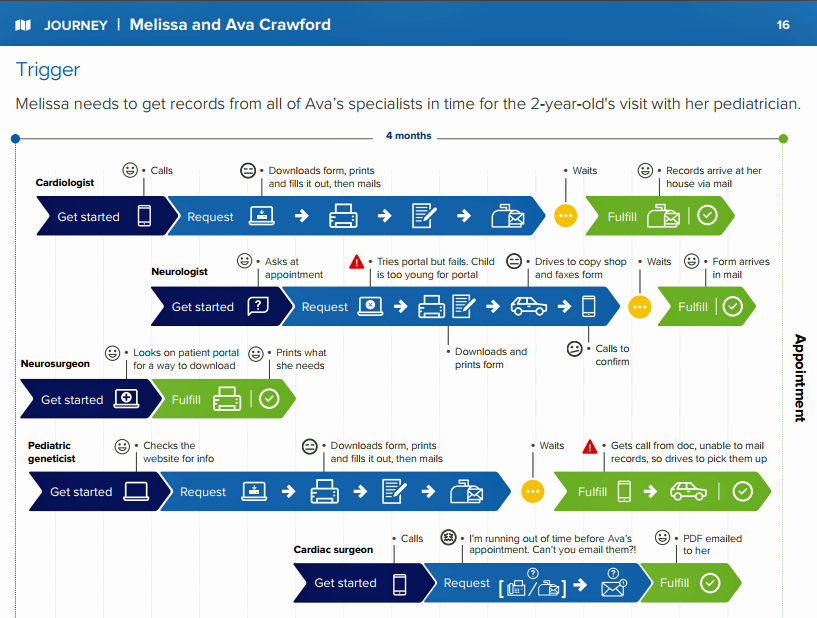

The general process of a patient requesting their health data works like this, illustrated by the patient journey of Melissa and Ava Crawford, a mother and toddler daughter portrayed in the ONC report:

The general process of a patient requesting their health data works like this, illustrated by the patient journey of Melissa and Ava Crawford, a mother and toddler daughter portrayed in the ONC report:

- A patient/consumer makes an initial inquiry

- The consumer requests the records, which can be done via a paper authorization form (that is then completed and either mailed or faxed to a provider) or online via portal. Sometimes a consumer must write a letter request to the provider and mail or fax that paper ask.

- The consumer waits for a response, which ONC calls “a bit of a black hole for consumers.” This can be as long as 30 days under the HIPAA law.

- The health system receives and verifies the request, then verifies the patient’s identify and address.

- Health systems then fulfill the records request, often a printed copy of the medical record that can be faxed or mailed, PDF files, or a computer disk (CD).

ONC conducted research into the consumer journey along this process to identify opportunities to improve the patient experience of requesting and receiving personal health information.

![]() Health Populi’s Hot Points: Most Americans see their doctors entering medical information electronically, and most people say accessing all kinds of medical information is important, the Kaiser Family Foundation learned in a health tracking poll conducted in August 2016. However, there are big gaps in the information available to U.S. patients online, such as prescription drug histories and lab results: two very popularly demanded information categories. And through the consumer-patient demand lens, 1 in 2 U.S. adults said they had no need to access their health information online, as the chart from the KFF poll attests.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Most Americans see their doctors entering medical information electronically, and most people say accessing all kinds of medical information is important, the Kaiser Family Foundation learned in a health tracking poll conducted in August 2016. However, there are big gaps in the information available to U.S. patients online, such as prescription drug histories and lab results: two very popularly demanded information categories. And through the consumer-patient demand lens, 1 in 2 U.S. adults said they had no need to access their health information online, as the chart from the KFF poll attests.

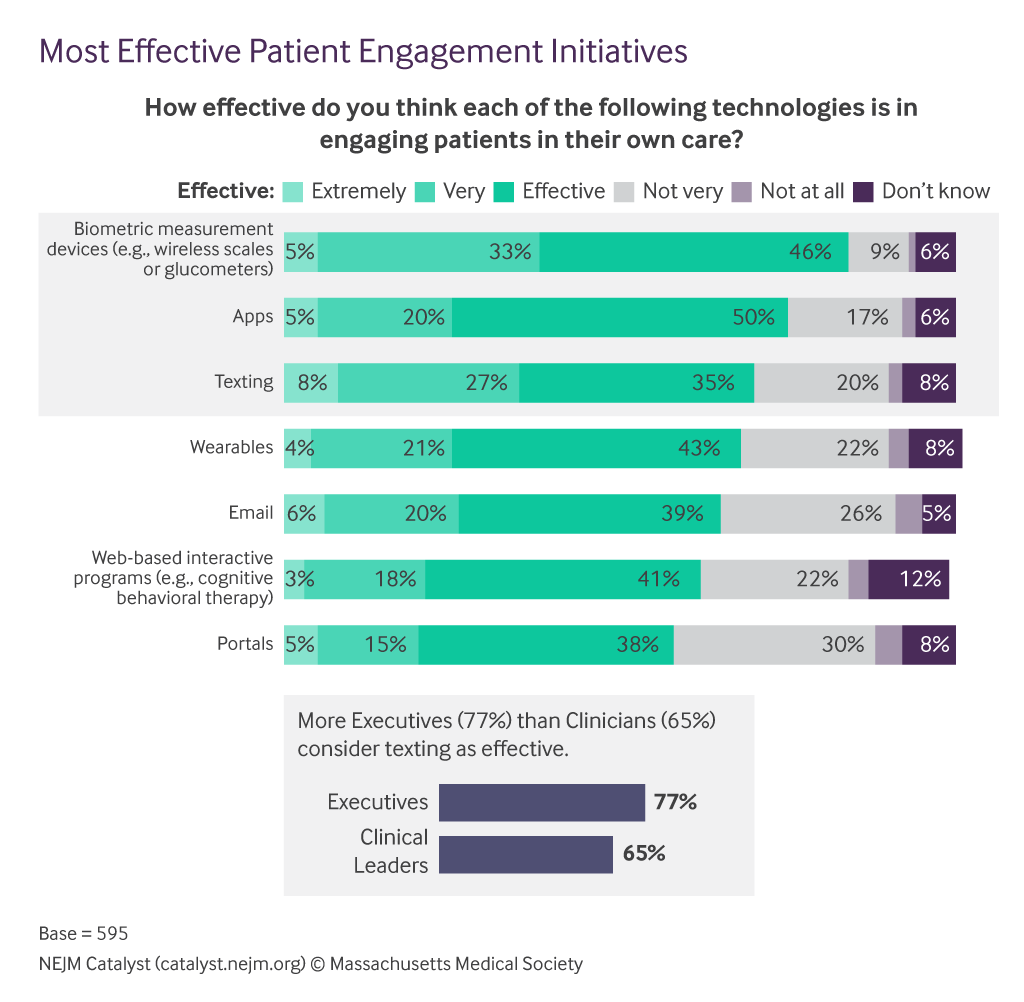

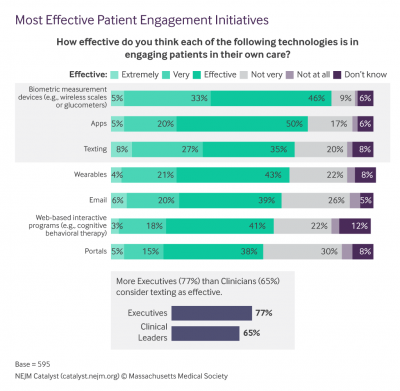

How to bridge the chasm between self-health IT, providers and patients? The most effective patient engagement technologies are biometric measurement devices like WiFi scales and glucometers, apps, texting and wearables — with portals ranking last — according to physicians and clinical leaders polled in a New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) survey published earlier this month.

The top benefit of engaging patients with these technologies is to support people in their efforts to be healthy, and to provide input to providers on how patients are doing when not in the clinic, this research found.

The top benefit of engaging patients with these technologies is to support people in their efforts to be healthy, and to provide input to providers on how patients are doing when not in the clinic, this research found.

My friend and collaborator Michael Millenson wrote in the BMJ this month about patient-centered care no longer being “enough.” In this era of technology-enabled healthcare, and rising consumerism among patients, three core principles must underpin the relationship between patient and provider:

- Shared information

- Shared engagement

- Shared accountability.

Michael quotes Jay Katz from his book, The Silent World of Doctor and Patient, who talked 35 years ago about the concept of “caring custody.” Jay explained this as, “the idea of physicians’ Aesculapian authority over patients'” being replaced with “mutual trust.”

It is not enough to build and offer a technology “meant” for patients and people to use for their health and healthcare. Trust underpins all health engagement, and must be designed and “baked” into the offering. Today, that trust is built as much on consumer retail experience (the last-best experience someone has had in their daily life, exemplified at this moment by Amazon) as in a new social health contract between providers and patients.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.