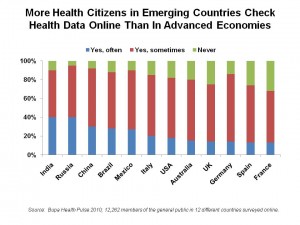

1 in 2 people who use the internet to seek health information do so to self-diagnose; this is highest in China, US, UK, Russia, and Australia. Furthermore, health citizens in emerging economies including India, Russia, China, Brazil, and Mexico, may rely more on online health searches than people in developed countries. In these regions, health seekers face high costs of face-to-face visits with medical professionals.

1 in 2 people who use the internet to seek health information do so to self-diagnose; this is highest in China, US, UK, Russia, and Australia. Furthermore, health citizens in emerging economies including India, Russia, China, Brazil, and Mexico, may rely more on online health searches than people in developed countries. In these regions, health seekers face high costs of face-to-face visits with medical professionals.

These global findings come out of the report, Online Health: Untangling the Web, from Bupa. Bupa is a health company based in the UK that serves 10 million members in 190 countries, and another 20 million through Health Dialog. The report is based on the Bupa Health Pulse 2010 survey conducted online by Ipsos MORI among 12,262 people in 12 countries between June and July 2010.

Some context here will be useful: in European Union (EU) member states, the total e-health spend accounted for 5% of total health budgets by the end of 2010, compared with 1% in 2000. The EU has made it a priority to develop an e-health infrastructure across the community: the report quotes Eleni Christodoulou, et. al., who wrote the definitive report on the role of eHealth in the expanding EU; this defines the eHealth infrastructure as, “the use of modern information and communication technologies to meet the needs of citizens, patients, healthcare professionals, healthcare providers and policymakers. It makes use of digital data, transmitted, stored and retrieved electronically, for clinical, educational and administrative purposes, both at local sites and at a distance from them.” Thus, the EU recognizes that the internet will be increasingly used in health for its citizens.

The most common activities individuals undertake, globally, using the internet for advice on health include

- Information on medicine (among about 7 in 10 people)

- Self-diagnosis (done by nearly one-half of people polled)

- Learning from other patients’ experiences (4 in 10)

- Information on hospitals and clinics (4 in 10)

- Information on doctors (about 1 in 4).

Social networking in health is limited, at about 18% of respondents in the Bupa survey who use a social network for health purposes (e.g., Facebook, MySpace). The use of Twitter to post about health gauged only 5% of respondents in this survey across all countries polled.

The U.S. appears to be the world’s headquarters for global health information seekers’ favorite health websites: most of the top 20 health sites are based in the U.S. After U.S. health citizens seeking info, people from India, the UK, Australia and China are the highest utilizers of U.S.-based health portals. The most popular sites used by health citizens globally include the U.S. National Institutes of Health, WebMD, PubMed, Medicinenet.com, Natural Health Information Articles and Health Newsletter (mercola.com), Medline, Drugs.com, Medscape, and the US Patent and Trademark Office AIDS Patents Database.

Google and Yahoo — general search engines — are used most often for health searches globally, with the top kinds of health information sought being information on specific diseases or medical problems, medical procedures, and exercise/fitness information.

There are, of course, differences in how the globe’s health citizens use the internet. For example, seeking information about medical professionals (doctors) is relatively common in the U.S. and India. However, the proportion of health citizens seeking information about doctors in the UK and France is quite low, at 12% and 14%, respectively.

Some methodology details on the survey sample: In Brazil, China, Mexico and Russia, the quota for age was set to be nationally represented up to age 50. In India, quotas were set on age, gender and region to represent the national population.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The rationale for health engagement is in the eye of the beholder – in this case, the patient or health consumer. In the case of health citizens who live in emerging countries where accessing health providers can be relatively expensive, the internet can play the role of “Dr. Google.”

The internet, though, can be utilized to deploy cost-effective and -attractive medical consultation beyond just information search for self-diagnosis. Think of how American Well or TelaDoc-style services could be deployed in areas where people lack access to a trained clinician, whether primary care physician, specialist, nurse practitioner, diabetes educator, or other medical professionals. While I’ve long asserted that “health care is local” when you’re analyzing markets for supply and demand, the internet and health citizens’ willingness to embrace participatory health care changes the maxim to, “global health care expertise can be consumed locally.”

But health engagement and patient activation cannot be assumed away even when such services might be available. In the United Kingdom, which is this survey has the greatest penetration of internet access across all countries polled, 1 in 5 people don’t go online for any reason — not just health, but all reasons. Furthermore, the Bupa Health Pulse 2010 found that the use of the internet to seek health information online varies with age, and drops sharply in people age 35 and over across all 12 countries surveyed.

Many challenges persist when it comes to patients getting to quality health information online. There are problems on both the supply and demand side of this equation: on the health information supply side, for example, that the Lancet study linking vaccines to autism was this week found to be fraudulent, not just ‘bad science;’ and on the patient-demand side, that people too often don’t check health information sources, a reality found in the Bupa survey.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...