The theory behind “consumer-driven health care” is that when the health care user has more financial ‘skin in the game,’ they’ll become more informed and effective purchasers of health care for themselves and their families. That theory hasn’t translated into practice, based on data from the Employee Benefits Research Institute’s (EBRI) latest Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey.

The theory behind “consumer-driven health care” is that when the health care user has more financial ‘skin in the game,’ they’ll become more informed and effective purchasers of health care for themselves and their families. That theory hasn’t translated into practice, based on data from the Employee Benefits Research Institute’s (EBRI) latest Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey.

Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) began appearing in employer benefit packages around 2001, with Health Savings Accounts emerging in 2004. 20% of large employers (with >500 employees) offered either an HRA or HSA plan in 2010, covering 21 million people or 12% of privately insured people in the U.S. Among these, there were 5.7 million accounts in 2010 containing $7.7 billion (including a couple thousand dollars from my own household).

Employees with HRAs and HSAs who exercised, didn’t smoke, and weren’t obese had higher account balances and higher rollovers than those who had less healthy behaviors.

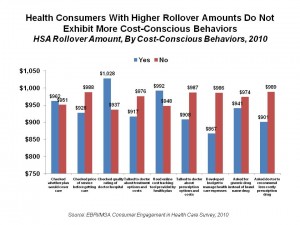

EBRI asked employees with HRAs and HSAs questions concerning cost-conscious health behaviors to see if there was a link between those behaviors — representing cost- conscious processes for health decisions — and account balances. EBRI’s hypothesis was that the higher the account balance, the more likely the individual engaged in the behavior. All of the questions are arrayed in the chart; these include checking whether the employee’s health plan covered a medication; checking the price of a doctor’s visit; checking a quality rating of a hospital; talking with a doctor about the cost of treatments and prescriptions; and asking for generic drugs.

No relationship was found between either HRA/HSA account balances or rollover amounts (shown in the chart) with respect to cost-conscious behaviors.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Over the past decade, employee benefits consultants and certain health policy theorists have pointed to consumer-driven health care (CDH) delivered through healthcare reimbursement accounts as an effective vehicle for bending the cost curve of health in the U.S. EBRI’s data should give CDH proponents pause. Consumers don’t behave in straight-line, lock-step fashion when it comes to health care consumption: the general rules of Economics 101 don’t apply for a whole range of reasons I and many other economists have discussed. Here’s a post I wrote in February on Anthem’s price hikes that highlights some aspects of market failure in health care.

Don’t assume that consumers having more financial skin in the health care game will make them smarter health consumers. Many health citizens make what seem to be smart fiscal decisions for health care consumption in the short run — like postponing visits to doctors when they feel ill, or skipping doses of medication. These often lead to longer-term dismal physical outcomes.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...