U.S. employers’ health insurance-response to the nation’s economic downturn has been to shift health costs to employees. This has been especially true in smaller companies that pay lower wages. As employers look to the implementation of health reform in 2014, their responses will be based on local labor market and economic conditions. Thus, it’s important to understand the nuances of the paradigm, “all health care is local,” taking a page from Tip O’Neill’s old saw, “all politics is local.”

U.S. employers’ health insurance-response to the nation’s economic downturn has been to shift health costs to employees. This has been especially true in smaller companies that pay lower wages. As employers look to the implementation of health reform in 2014, their responses will be based on local labor market and economic conditions. Thus, it’s important to understand the nuances of the paradigm, “all health care is local,” taking a page from Tip O’Neill’s old saw, “all politics is local.”

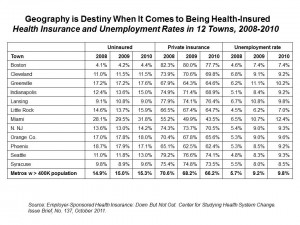

The Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) visited 12 communities to learn more about their local health systems and economies, publishing their findings in an October 2011 Issue Brief, Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance: Down But Not Out.

Overall, metropolitan areas with over 400,000 residents had a 15.5% rate of uninsured in 2010, and nearly 10% unemployed. The chart illustrates O’Neill’s paradigm: from a health insurance standpoint, it’s good to live in Boston, given its 4.4% uninsured rate and 8.4% level of unemployment — both low levels compared with the 11 other communities analyzed by HSC. In 2010, Miami had an uninsured rate of 31.8% — double the national rate — and an unemployment rate of 12.4%. Orange County CA had an 18% level of uninsured, but an average level of unemployment.

Employers who continued to provide health insurance bore a 113% cost increase between 2001 and 2010, and those who continued to provide insurance allocated more costs to employees in the forms of premium sharing and greater cost-sharing for provider visits, clinical services and prescription drugs. In particular, consumer-directed health plans (CDHP) grew, with 50% of workers in small firms (under 200 workers) now enrolling employees in CDHPs. These plans largely focused on the cost side of the health care savings equation, and didn’t promote consumer engagement in their personal health. In addition to CDHPs, health plans marketed limited benefit plans with lower premiums in the small-group market.

Focusing on the cost-side of health insurance led employers and their benefits consultants to target utilization management of high-cost services, providers’ practice patterns (e.g., prior authorization and retrospective review), and a sharper scalpel to specialty drug expenses for which there are generally no generic substitutes.

While there is a growing cadre of large employers interested in expanding wellness for employees, taking a long view on this investment, smaller firms have not been as keen to include wellness activities because they increase up-front costs with an ROI for some time. HSC writes, “Cost pressures from the recession made small employers especially wary of paying additional premiums upfront for the promise of payoffs down the road.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: HSC predicts that large, private sector employers will likely continue to provide health insurance to employees and continue to shift even more costs onto workers. CDHPs would be the predominant plan design to enable greater cost-sharing in the next couple of years. The wild card for forecasters is how employers will react to the Affordable Care Act in 2014, and what the economy will look like by then. A key uncertainty is how the local/regional health insurance exchanges will be implemented and what their offerings will be.

Making a national forecast is made difficult by the reality of state and local economies, labor force issues, and health care delivery structures and cultures. We see this week that state Governors are cutting dollars from Medicaid as part of their budget-balancing mandates: what’s a state executive to do when faced with such a mandate, where health care and education are the top two budget line items for most Governors?

Furthermore, the 50 Medicaid programs (funded by state and Federal coffers) will be further stressed by unemployment and the lagging economy, as workers either lose health insurance coverage or determine they cannot afford to opt-in to more expensive coverage offered by their employers in the consumer-directed health plan era.

The lack of consumer engagement strategies in health for health plans serving the small employer market is an epic fail for both workers and employers. Every dollar spent on health “care” for workers can be maximized by getting people more involved in their health, through artful health plan design (learning from, for example, the Asheville experiment), promoting and incentivizing the use of tools for remote health monitoring, and teaching people more about self-care options in the retail health milieu. Finally, getting to the bottom of noncommunicable diseases that are caused by 4 key factors — smoking, eating too much, not moving around enough, and drinking to excess — would help bend the cost curve driven by chronic disease in the U.S. These are the conditions with avoidable expenses: obesity and metabolic disorder/diabesity, along with heart disease. Simply allocating more costs onto employees isn’t going to re-engineer the engaged patient.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...