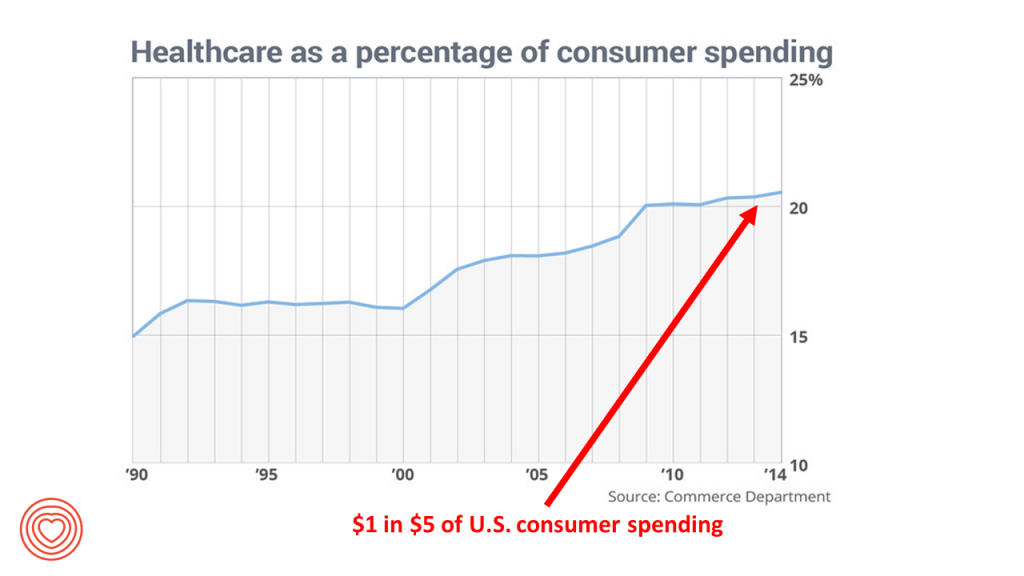

Consumers spend one in five dollars of their household budgets on healthcare in America. This fiscal reality is motivating more U.S. health citizens to seek information and control for their and loved ones’ health care. Personal health technologies will play a growing part in peoples’ self-care outside of the healthcare system and, increasingly, as part of their care prescribed by clinicians and (to some extent, for the short-term) paid-for by payors – namely, employers and government sponsors of health plans.

This week is the Disneyland event for the personal tech aficionados known as CES (once called the Consumer Electronics Show). 2017 is the 50th anniversary of this conference, which brings together lovers of all sorts of technology, which is broadly defined at this meeting: “tech” includes cars and TVs, headphones and 3D printing, drones and washing machines, videogames and smart home products. And, digital health technology is a key growing category at CES, as well, and has been for the past several years.

My advisory work focuses on the intersection of consumers, health and technology, so CES has become a major locus of connecting with the tech developers, companies, clients, and thought leaders in the field — and increasingly, new entrants outside of healthcare looking to play a role inside that 20% of the national US economy.

My advisory work focuses on the intersection of consumers, health and technology, so CES has become a major locus of connecting with the tech developers, companies, clients, and thought leaders in the field — and increasingly, new entrants outside of healthcare looking to play a role inside that 20% of the national US economy.

To put this week of digital health-tech optimism into some economic perspective, I’ll point to two articles published in JAMA (the Journal of the American Medical Association) just last week (issue dated 27th December 2016). The original investigation article is on US Spending on Personal Health Care and Public Health, 1996-2013, written by an interdisciplinary team from the worlds of academia, NGOs, and government agencies. The second article is a response to the first, from Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, titled, How Can the United States Spend Its Health Care Dollars Better?

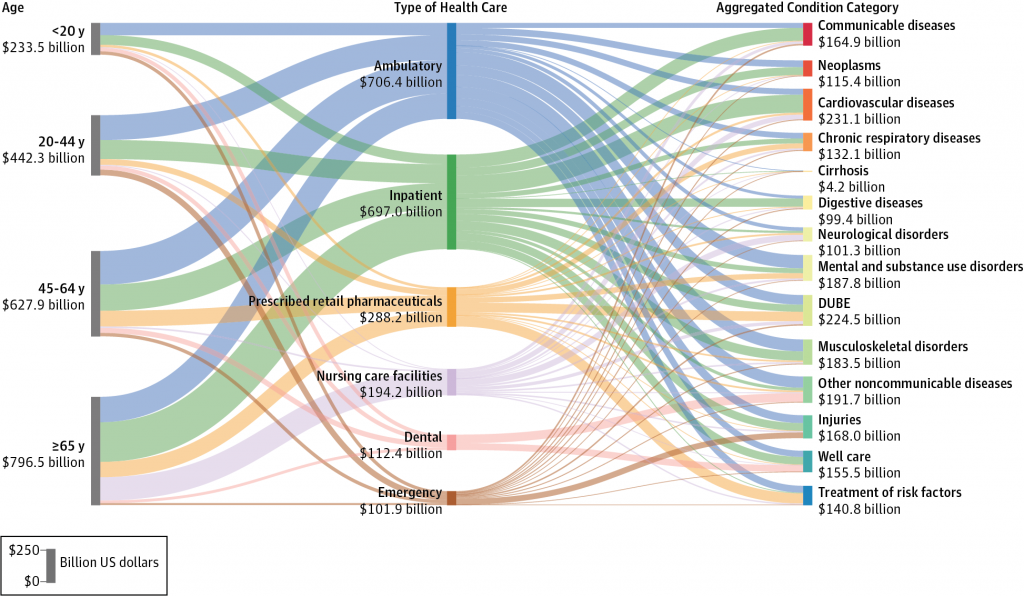

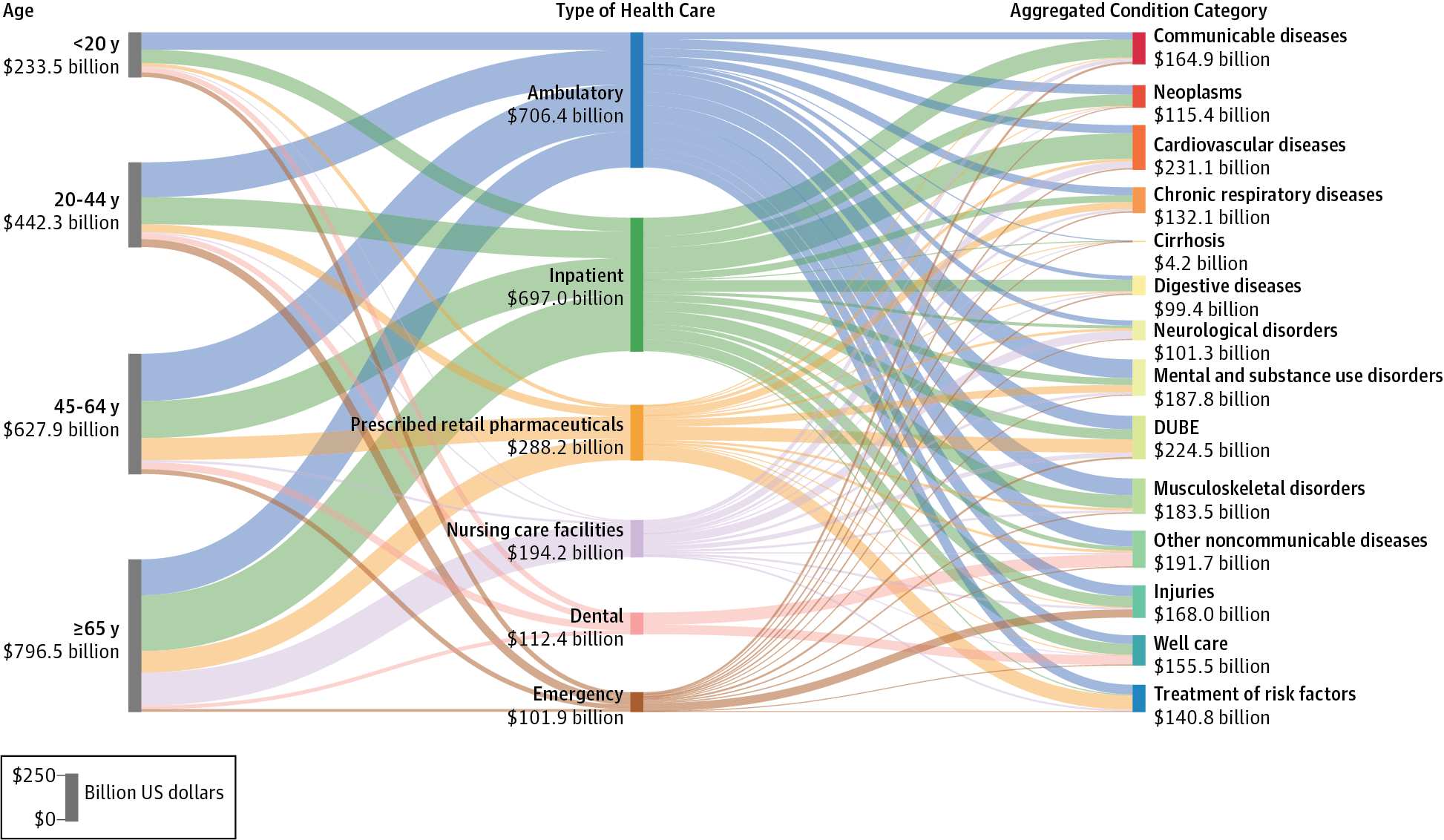

The goal of the first article was to quantify how US spending on different health conditions has changed over time and by demographics of the nation’s population. The researchers looked at 155 conditions by age and gender, and by type of care. The greatest spending was on diabetes, with some $101 bn in health spending in 2013 split between pharmaceuticals (58%), ambulatory care (24%), and other care categories. The second highest spending category was on heart disease, with $88 bn of spending, followed closely by low back and neck pain in third place amounting to just under $88 bn. Spending on pain and diabetes increased the most dramatically over the 18 year period studied.

In Dr. Emanuel’s response, he writes that, “By 2020, health care spending in the United States is expected to surpass the national economy of Germany, at which point the US health care system will be the fourth largest economy in the world.”

This begs Zeke’s question asked in the title – how can the US spend its health care dollars better?

Some of his observations that respond to the question are that:

- Most healthcare spending is for chronic conditions, like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, cancers, and cirrhosis (liver disease, largely caused by alcohol over-use).

- Spending on behavioral health is under-emphasized, especially recognizing that chronic conditions are so often accompanied by mental health issues which can compromise treatment. Co-morbid anxiety, for example, adds up to $615 more per patient per month, and diabetes combined with depression, $560 more per patient per month (based on research from the actuaries at Milliman). Bundling behavioral/mental health into primary care can help stem healthcare costs and improve outcomes.

- Health care spending on physical pain, and especially lower back pain, runs $88 bn a year, with $48 bn more going to osteoarthritis and $45 bn to other joint and connective tissue conditions. That’s a total of $150 bn spent, while pain-related health problems are increasing in the US population. Bundling payments for pain-related conditions would help to incentivize providers to deal with pain more holistically.

- Spending on public health and prevention is disconnected from spending on acute care. Yet, the social determinants of health largely determine chronic conditions. Consider the health impacts of smoking, poor nutrition, lack of exercise, substance abuse, lack of clean water, and unsafe neighborhoods, and you begin to understand the major impact of the social determinants of health on morbidity and, ultimately, mortality.

These health economic findings set the stage for digital health at CES 2017: that patients, now health consumers, can help make their health by adopting evidence-based technologies to help manage chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and pain. There will be other technologies shown this week at #CES2017 from new entrants into digital health looking into building the smart and connected home that can begin to sense issues around air quality, safety, personal emergencies, and a well-stocked refrigerator.

But technology alone is not a panacea for sound public policy around the social determinants of health (like sound food and nutrition policies and early childhood education), along with rational health care payment regimes that incentivize providers, payors and patients to work together on making whole health. These policies would recognize the whole person in real life with a real household budgets — and not just pay for treatment of an organ system in isolation.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...