To succeed in the business of health information technology (HIT), a company has to be very clear on the problems it’s trying to address. Now that EHRs are well-adopted in physicians’ practices and hospitals, patient data have gone digital, and can be aggregated and mined for better diagnosis, treatment, and intelligent decision making. There’s surely lots of data to mine. And there are also lots of opportunities to design tools that aren’t very useful for the core problems we need to solve, for the clinicians on the front-lines trying to solve them, and for the patients and people whom we ultimately serve.

At the end of each day, the HIT company has to remember that at the end of a digital transaction, there’s a person. That individual could be a member of a health plan, a nurse, a physician, a grandparent-caregiver tapping into her grandchild’s medical portal…all people, with different abilities to read and comprehend data, values, and incentives.

Earlier this week, I spent a day with Medecision’s digital health team, aka ‘the Liberators.’ My role in the event was to provide a through-line from introductions to trend-weaving what I heard and learned at the end of the day. In the middle of the day, I spoke about trends in health care focusing on the patient: as a payor, as im-patient, as digital, as a consumer, and as political.

Earlier this week, I spent a day with Medecision’s digital health team, aka ‘the Liberators.’ My role in the event was to provide a through-line from introductions to trend-weaving what I heard and learned at the end of the day. In the middle of the day, I spoke about trends in health care focusing on the patient: as a payor, as im-patient, as digital, as a consumer, and as political.

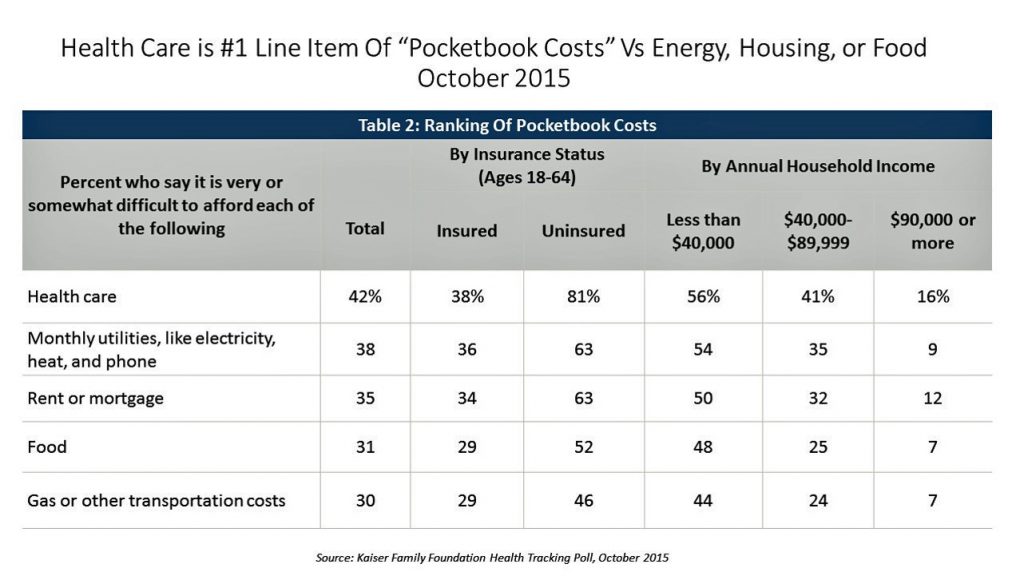

As a payor, the insured patient in 2019 is likely to be managing a high-deductible health plan, responsible for first-dollar costs until s/he reaches that threshold. As such, health care spending feels like a retail event, prompting the patient-as-payor to ask, “what’s the price?” “What’s the value?” “What’s the product?” “What are the alternatives?” Even though price transparency has gone live online among more hospitals, this start-up phase is still heavy-lifting and confounding for people to understand. Health care costs continue to be the top pocketbook issue for most families in the U.S. across income cohorts.

As a payor, the insured patient in 2019 is likely to be managing a high-deductible health plan, responsible for first-dollar costs until s/he reaches that threshold. As such, health care spending feels like a retail event, prompting the patient-as-payor to ask, “what’s the price?” “What’s the value?” “What’s the product?” “What are the alternatives?” Even though price transparency has gone live online among more hospitals, this start-up phase is still heavy-lifting and confounding for people to understand. Health care costs continue to be the top pocketbook issue for most families in the U.S. across income cohorts.

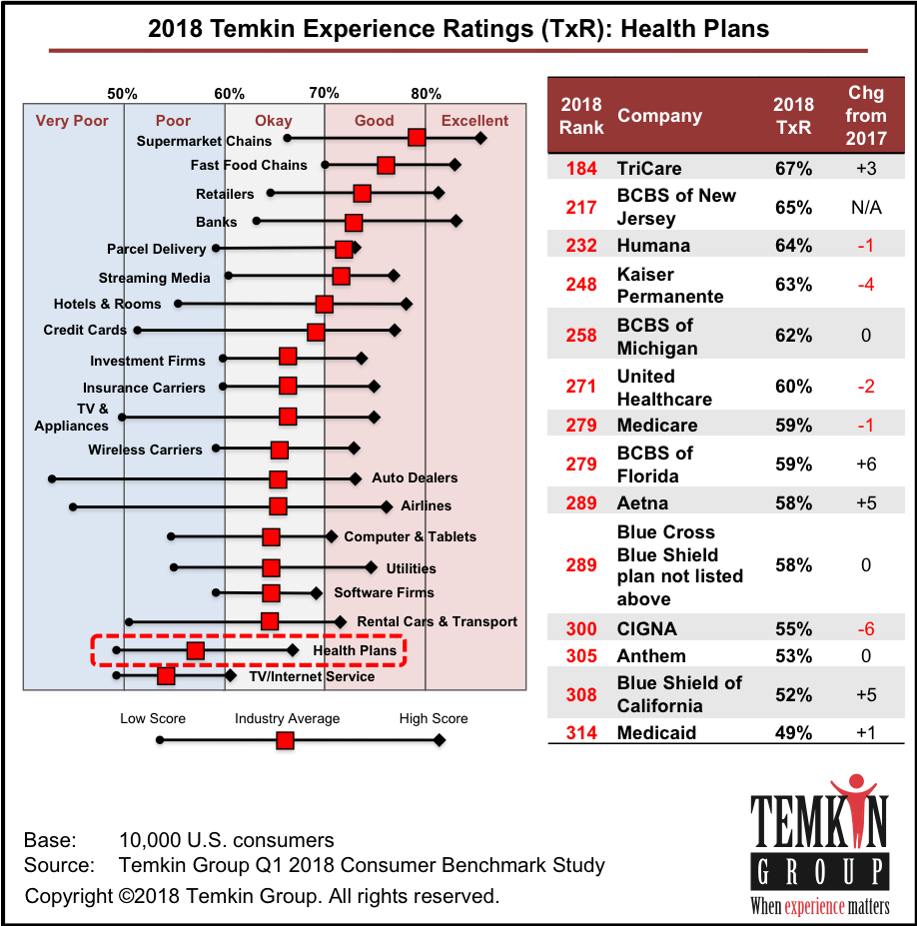

As that payor, expecting retail service, patients are im-patient. Why can’t appointments be made online like I do with restaurants on OpenTable? What’s so hard about getting me my lab test on the day or next-day after I provide my sample? Health care surely doesn’t feel like the best retail experience, and that’s especially true for health plans. I shared the Temkin Group’s data on customer experience (shown here), where our favorites are found in grocery stores, fast food joints, and retailers. Health insurance plans? Not so much.

Patients are also digital: smartphones are fairly ubiquitous (although we must remember that not all people can afford data plans – my mantra, that connectivity and broadband are a social determinant of health). This means people (with connectivity) want work-flows for health care the way they conduct their financial affairs, social networking, travel planning, and way-finding. People are omni-channel, too, so health care must think like a retailer in reaching people wherever and however they want to be reached: online, via email, via text, phone call, and even via snail mail for some (albeit increasingly fewer) patients.

Patients are also digital: smartphones are fairly ubiquitous (although we must remember that not all people can afford data plans – my mantra, that connectivity and broadband are a social determinant of health). This means people (with connectivity) want work-flows for health care the way they conduct their financial affairs, social networking, travel planning, and way-finding. People are omni-channel, too, so health care must think like a retailer in reaching people wherever and however they want to be reached: online, via email, via text, phone call, and even via snail mail for some (albeit increasingly fewer) patients.

Patients are consumers, at the end of the day. As payors, digital beings, im-patient people demanding service levels they experience elsewhere — outside of healthcare.

Finally, patients are political. Health care was the top issue driving voters to the 2018 mid-term elections. Health care will also be top-of-mind among voters in 2020, who are becoming more aware of the risks of losing coverage. This week, the level of uninsured people in America rose to a four-year high, with the erosion of support for the Affordable Care Act by President Trump and Congress over the past two years. Growing concern for losing coverage for pre-existing conditions has become mainstream across political parties.

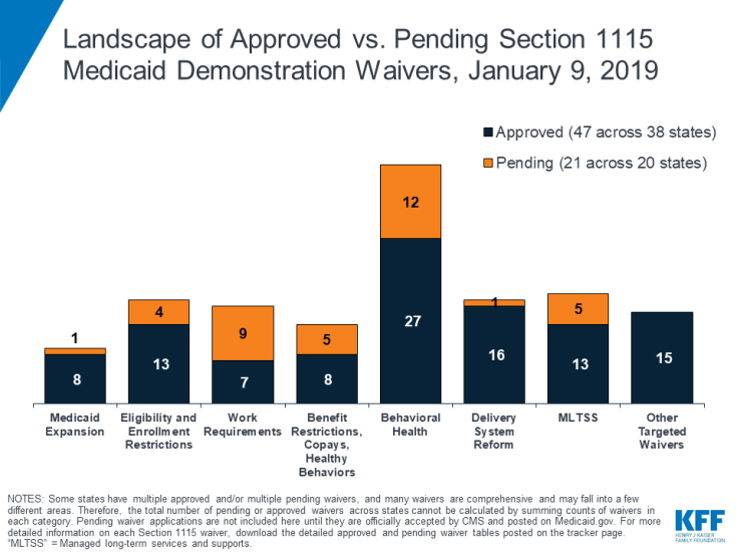

Politics underpin what’s happening in health plans in the public sector, and I spoke a bit about Medicare and Medicaid. The latter is the place to look, across the fifty State Governors, for Medicaid expansion (or not); growing integration of behavioral health to deal with depression, anxiety, and the opioid crisis; and greater attention to the social determinants of health and long term social supports (LTSS). You can see the latest Medicaid demonstration waiver data from a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis done January 9, 2019 shown in the bar chart.

Politics underpin what’s happening in health plans in the public sector, and I spoke a bit about Medicare and Medicaid. The latter is the place to look, across the fifty State Governors, for Medicaid expansion (or not); growing integration of behavioral health to deal with depression, anxiety, and the opioid crisis; and greater attention to the social determinants of health and long term social supports (LTSS). You can see the latest Medicaid demonstration waiver data from a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis done January 9, 2019 shown in the bar chart.

To that point, during the day, two Medecision Liberators played out a scenario for complex cardio management. In the role play, a patient-persona was speaking with a call center associate. In the conversation, the plan member asked how the associate knew so much about them. Further into the conversation, the member said she needed to hurry off the call to get to her bingo game in time.

To that point, during the day, two Medecision Liberators played out a scenario for complex cardio management. In the role play, a patient-persona was speaking with a call center associate. In the conversation, the plan member asked how the associate knew so much about them. Further into the conversation, the member said she needed to hurry off the call to get to her bingo game in time.

That conversation raised two important points and opportunities to drive health outcomes: first, on the issue of privacy and trust, as the member questioned just how the associate knew so much about her. That’s an opportunity to forge a bond of trust between the member and the health plan or provider, to discuss how bringing various data together can help paint a picture of her whole life and help her achieve better health.

The second item — the bingo game — presented an opportunity to discuss social supports, transportation to the event, and what the member might be snacking on during bingo. If it turns out she loves the salty snacks or M&Ms, the health coach has an opportunity to counsel the member on the impact of salt on her heart health, and suggestions for some healthier snacking.

This kind of conversation is inherent in the values that Health New England’s Lisa Holland discussed in the context of HNE’s customer promises for the organization: quality, thoughtfulness, and humanity.

The Medecision Liberators collaborated in a brainstorming exercise about social determinants of health, generating important insightful questions they would ask people about their lives to un-earth opportunities to address social supports. A few of these questions were:

- What’s your most challenging daily activity?

- Walk me through your typical day.

- Do you have someone you can rely on if you need help?

- What does living independently look like to you?

- Do you have access to healthy food?

- What did you do for entertainment today that gave you pleasure?

- Can you read?

That led me to end the day’s trend-weaving quoting one of my favorite JAMA columns from the recent past: that Value-based payments require valuing what matters to patients, co-written by Dr. Joann Lynn, Dr. Aaron McKethan, and Dr. Ashish Jha. This has become a pillar in my thinking about the role of respect and trust in health care between patients (as payors, consumers, self-carers and caregivers) and health care organizations. They ask and answer: “How can a care system be structured to deeply respect the myriad differences among patients when disabilities or advanced age makes those differences especially important? The answer is that the delivery system must proactively help affected people articulate their priorities and goals.”

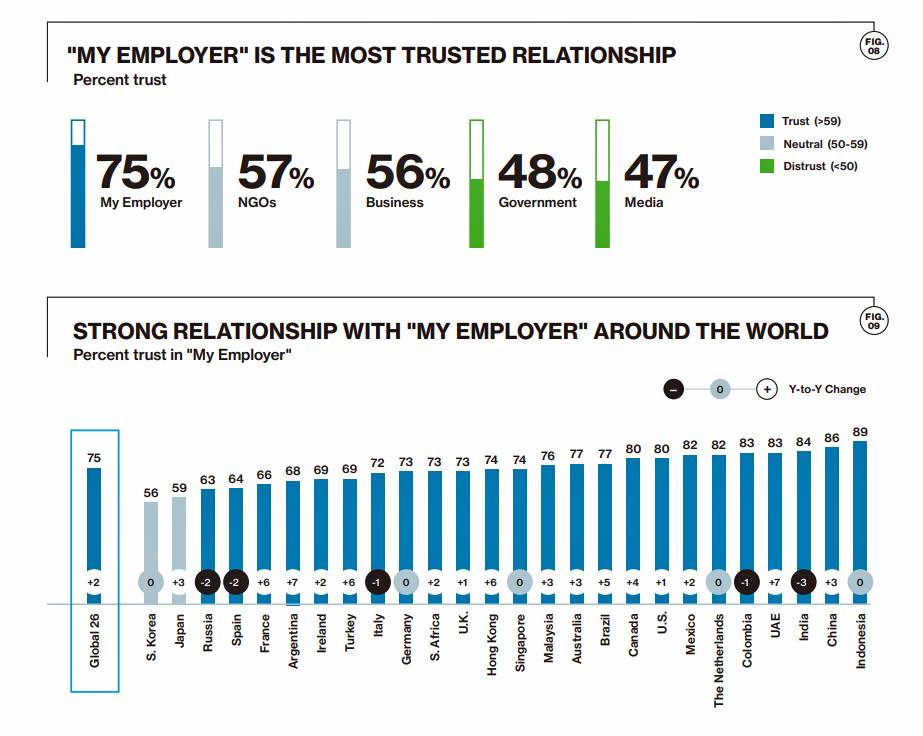

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The theme of trust was mentioned throughout the day, across a wide range of discussion topics. I noted in closing that this week also convened the World Economic Forum in Davos, during which Edelman annually updates their Trust Barometer. This year’s survey found that globally in 2019, the most trusted institution for consumers is the employer: both for ensuring a job for “me,” as well as for being a good corporate citizen in the community locally and in the larger world, in sustainability and responsibility.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The theme of trust was mentioned throughout the day, across a wide range of discussion topics. I noted in closing that this week also convened the World Economic Forum in Davos, during which Edelman annually updates their Trust Barometer. This year’s survey found that globally in 2019, the most trusted institution for consumers is the employer: both for ensuring a job for “me,” as well as for being a good corporate citizen in the community locally and in the larger world, in sustainability and responsibility.

This behavior drives trust, which we learned is the most important driver behind peoples’ engagement in health — a key finding in the first Edelman Health Engagement Barometer conducted in 2008. Eleven years later, trust as a health engagement requirement is even more important in light of our AI-enabled health care world.

We remember that at the end of every health IT transaction, there’s a person: a plan member, a consumer, a doctor, a caregiver.

“We are all the same,” a doctor’s essay in JAMA noted this week. Dr. Mandy Maneval, a family practitioner in Mifflintown, PA, wrote:

It strikes me that so many of life’s moments are dichotomies of health and disease, life and death, joy and sorrow. As a family medicine physician, this mirrors my everyday life. I often leave one patient’s room after giving bad news and immediately enter the next room to see the happy parents of a newborn. Navigating the full spectrum of human emotion is simultaneously exhilarating and exhausting. There are days when I feel like a hero and others when I cannot do a thing right…Connecting deeply through our shared humanity, no matter our differences, is one of the most precious gifts we offer and receive as physicians. We are all the same.

That works for physicians, and it works for all of us in the health care ecosystem. I thank Medecision for the opportunity to participate in this day of insights, team-building, and real human connection.

That last sentence was going to be the conclusion of this post. But just in time, on cue as this post was being scheduled on WordPress, an article titled A Framework for Increasing Trust Between Patients and the Organizations That Care for Them arrived in my inbox from JAMA published on 24th January 2019. Dr. Thomas Lee and colleagues explained:

Trust matters in health care. It makes patients feel less vulnerable, clinicians feel more effective, and reduces the imbalances of information by improving the flow of information. Trust is so fundamental to the patient-physician relationship that it is easy to assume it exists. But because of changes in health care and society at large, trust is increasingly understood to be at risk and in need of attention.

The authors outline potential approaches to increase trust between patients and health care organizations, which include:

- As a first step, leadership should acknowledge that trust is foundational and a trusting environment essential for good health care

- Measuring trust should be a standard part of evaluating patient care experiences, including those with health plans

- Transparency of patient care experiences should be part of measuring, monitoring and continually improving quality and safety

- Boards and leadership should routinely examine data that reflect on patient and staff trust, and include these in reward plans

- Standards, training and accountability systems should be developed for clinicians and for teams

- Relationships between patients and clinicians should be structured such that patients can make choices reflecting their personal preferences: this recognizes that patients know more about what matters to them and how they are doing

- Health systems should insure needs of patients for a navigator or translator are met

- Finally, patients should be actively engaged in designing solutions to the erosion of trust.

This article is free from JAMA’s usual paywall, so please click on the link above to access the entire discussion. These doctors who crowdsourced the recommendations really understand that it’s good to know about patient’s love of bingo, taste for salty snacks, and social support systems…and patients really do want to be part of their own planning and care.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...