“I’m in Berlin, and we don’t like walls,” Bart De Witte responded in a concluding Q&A session yesterday at the 2nd Symposium on the Future of Health Systems, convened by the World Health Organization (WHO) in Porto on 5th September.

Over two days, this meeting convened stakeholders focused on WHO’s European Region to support the Organization’s digital health action plan for 2023-2030 – which fosters cross-nation health planning covering the EU space.

AI’s promise in health care to automate and streamline administration, and augment diagnosis and treatment, comes with accompanying risks that can compromise ethics, human rights, equity, and patient privacy, among other thorny issues.

Bart founded the HIPPO AI Foundation after working for many years with global technology companies (IBM and SAP among them) in the health care ecosystem. He keeps a firm and passionate focus on the socio-economic impacts of technology in health care. I’ve known Bart for over 15 years, and consider him a key touchpoint for my own work, research and collegial community. As is his brand, Bart provided a lot of food for thought and inspiration which I’ve no doubt prompted the WHO meeting audience with simultaneous delight and also a bit of trepidation during his talk.

In his discussion titled, “Artificial Intelligence: gAIn or pAIn for European Health Systems?”, Bart had three objectives:

- To discuss what “openness” can do for inclusiveness in health care

- To break down dogmas about Open Source AI, and,

- To offer policy advice for developing regulations and guardrails that could ensure the democratization of health and data to inform better, more equitable health care systems.

Bart led with a statement about HIPPO AI’s purpose, which is:

- To empower patients

- To connect humans

- To unite data

- To foster Regenerative Medical AI

- Toi defeat global inequalities, and

- To accelerate inclusive innovation.

The fine print under the title of this slide is the effort’s over-arching goal: to democratize AI in medicine.

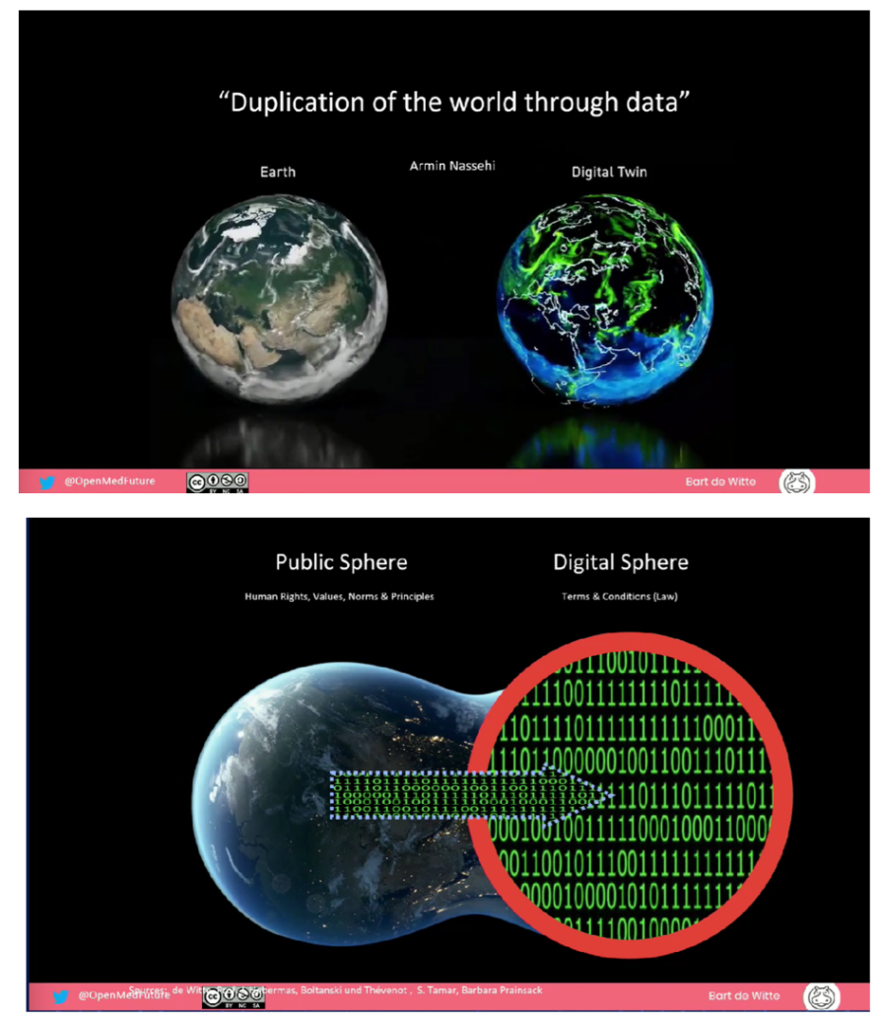

In explaining the rationale toward openness, Bart talked about early AI models for weather prediction which benefited the public-at-large. By duplicating the world through data, researchers could model the weather and enable people to prepare for storms and incidents in advance of their arrival.

With more data, the modeling can address even more complex processes — for health/care, supporting drug discovery and diagnosing rare diseases, for example.

In “duplicating the world through data,” this diagram from Bart’s talk illustrates a shift from the public sphere to the digital. It’s in that shift where asymmetries, inequalities, and other potentially unintended (or mal-intended) outcomes evince.

Here Bart takes a page out of Habermas and team on structure change in the migration from the public sphere and social value to the private sphere’s incentives for economic value. Norms shift from one sphere to the other, which as the process of data “assetization” can kick in.

This prompts us to consider data as a common good, a Data Commons. Bart and colleagues are working to create an index of various AI systems and rating them based on how they connect to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Consider these two exhibits Bart discussed: first, focusing on SDG 3 which is something most of us who have committed our careers to health care have in our core: SDG 3, the goal for good health and well-being.

In our search for sustainable health care systems, it’s important to connect various SDGs to avoid “common good washing,” or more generally, “green washing.”

For health care in the U.S. in the current moment, my own focus in working with health/care ecosystem stakeholders link #3 with some combination of the following — although all 17 SDGs help make health for all…

#1 No poverty

#2 Zero hunger

#4 Quality education

#5 Gender equality

#6 Clean water

#8 Decent work and economic growth

#10 Reduced inequalities

#13 Climate action, and

#16 Peace, justice, and strong institutions.

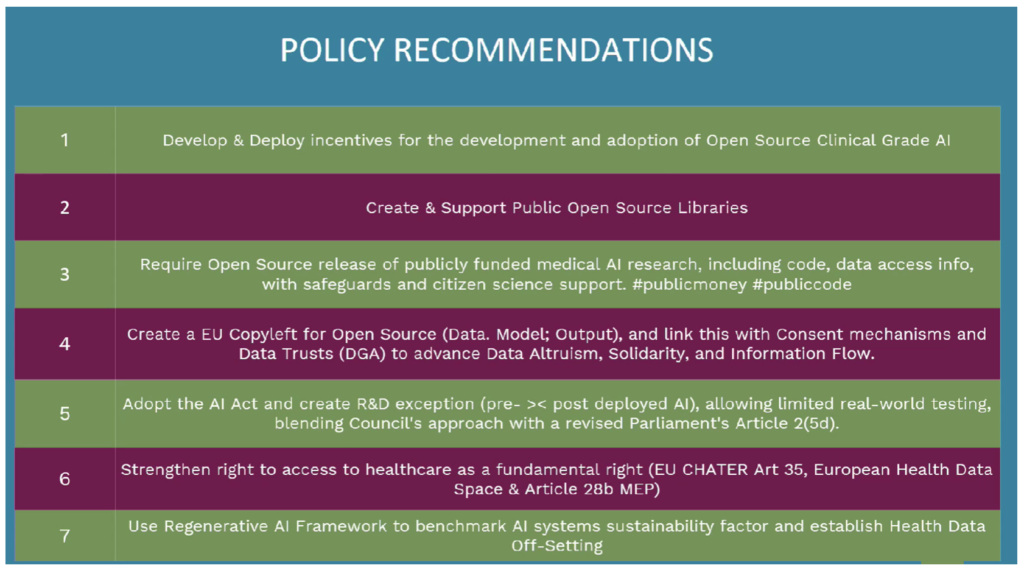

Bart covered many other ideas, but in the interest of attention spans for blog-reading, let me round out my takeaways with Bart’s policy recommendations summarized in these seven principles.

Open Source as a True North underpins the recommendations overall.

And open-ness also underpins another aspect of Bart’s raison d’etre: “I’m in Berlin and we don’t like walls so let’s not build any!”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: And now we turn here in the Hot Points to the topic of that Elevator mentioned in the title of this post.

In a panel following Bart’s eye-opening, mind-blowing talk, I was delighted to listen to the perspective of Dr. Ricardo Baptista Leite, a Portuguese-Canadian physician who was recently named as CEO of I-DAIR.

I-DAIR is a global organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with the mission of expanding access to inclusive and responsible research into AI and digital health. Dr. Baptista Leite is also a third-term Member of the Portuguese National Parliament and Head of Public Health at the Catholic University of Portugal.

Dr. Baptista Leite pointed out that we are in “Era Zero” for the future of machine learning and AI, and we have the opportunity to design from scratch.

That design ethos speaks to equity and trust.

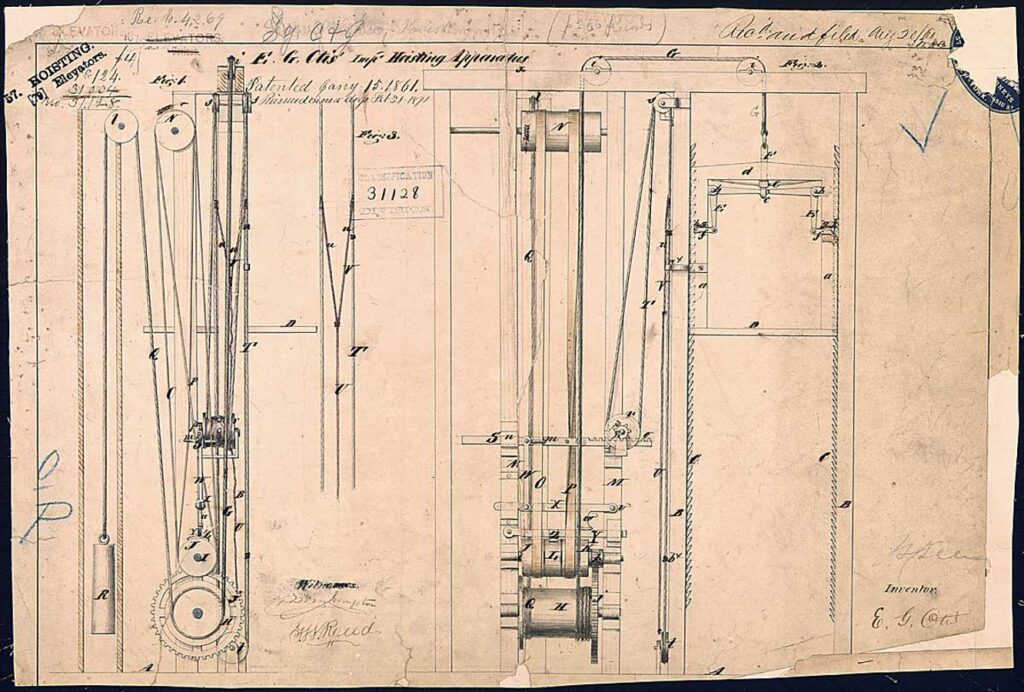

He took us on a time travel adventure back to the first U.S. World’s Fair held at the Crystal Palace, now known as Bryant Park, New York City, c. 1853-54. Here we meet Elisha Otis, one of the pioneer innovators of the elevator – and the patent-holder of a safety brake for that innovation.

As TIME magazine tells the story, before the safety brake was applied to the elevators that consumers could access, there were numerous accidents in the contraptions owing to often-breaking ropes that hoisted the lifts.

At the World’s Fair, brave elevator riders boarded the lifts and experienced, during dramatic drops, a safety brake kicking in. This inspired trust among consumers who were wary of opting in to boarding and riding on elevators.

And this innovation that drove trust then proceeded to change the concept of cities as we know them – where skyscrapers became possible because people trusted elevator rides up their many floors.

This metaphor that Dr. Baptista Leite shared further illustrates that, in health care, building on an already-broken model just exacerbates the challenges health citizens and clinicians already face in a disease-driven model – in a word, unsustainability.

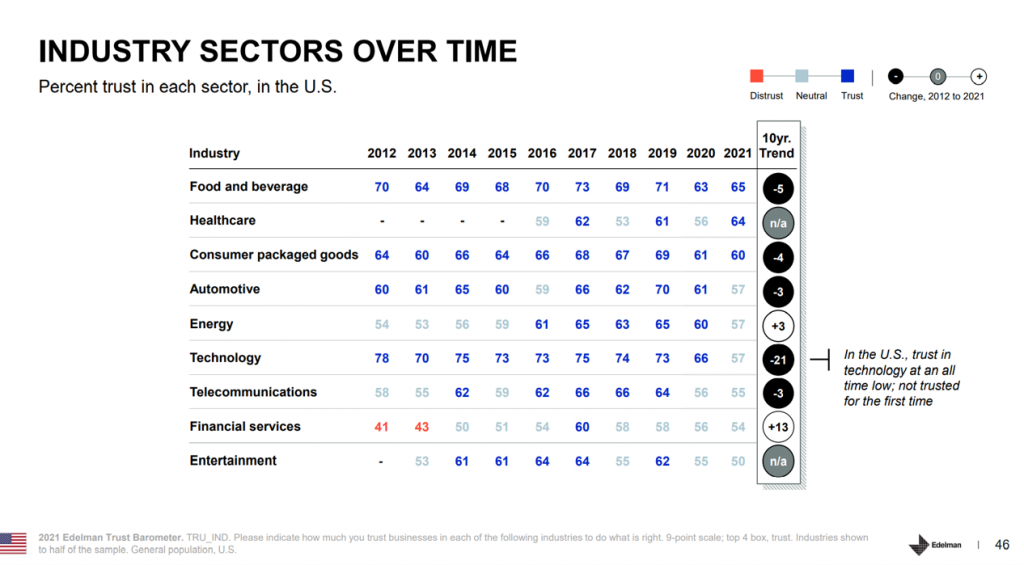

Trust, as we’ve discussed over many years here on Health Populi, is a key currency for health engagement. We’ve witnessed the decline of trust in health care, and in institutions – government, media, NGOs – quantified and tracked in the annual Edelman Trust Barometer.

When I recently wrote Trust-Busted: the Decline of Trust in Technology and What It Means for Health, I focused on Edelman’s finding that the U.S. public’s faith in Tech had tumbled to its lowest level since Edelman began measuring it in the study – falling 21 percentage points over 10 years from 2012.

As health citizens’ trust in medical information has reached a nadir, coupled with peoples’ loss of trust in technology, there’s an opportunity to educate people on the promise of AI and data for good – the opportunity for a Data Commons.

We’ve a long way to go and much work to do to accomplish this – but getting to sustainable, equitable, democratic health systems and data sharing? That’s one lift I’m ready to ride.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...