Several market forces are converging that boost patients’ ability to engage in their health and self-care, including peoples’ growing adoption of smartphones, demand for self-service and DIY lifestyles, and Americans’ growing responsibility as health consumers. Health consumers are using a growing array of self-health tools, enabled through digital technologies. However, these tools aren’t yet engaging some of the very people who need them the most: high-need, high-cost patients.

Research into this situation is discussed in the December 2016 Health Affairs article, Many Mobile Heaath Apps Target High-Need, High-Cost Populations, But Gaps Remain, published in the December 2016 issue of Health Affairs. For context, this research focuses solely on mobile health apps, and not the larger topics of telehealth and remote health monitoring.

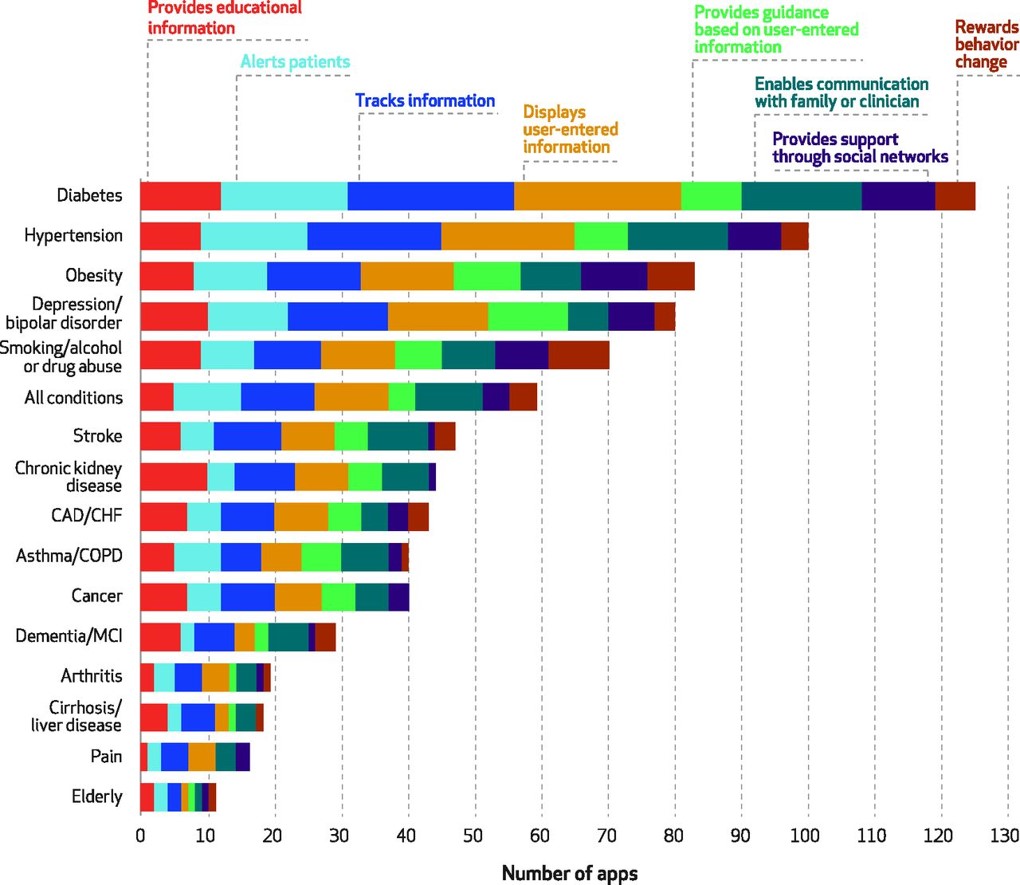

The team of researchers span several institutions, including the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and the Asan Medical Center in Seoul, Korea. The team mined mHealth apps in the iTunes and Google Play stores in February 2015. In addition, they searched medical special society websites for additional apps, as well as recommendations from experts in the field. To narrow down the apps for the high-cost, high-need patient population, the researchers focused on many search terms of common chronic conditions (e.g., alcohol, asthma, bipolar, heart disease, diabetes, obesity, smoking, and stroke among them). The group focused in on 166 apps targeting the vulnerable study population of high-need, high-cost patients.

The team found the following:

- Apps do exist and most track patient data. However, many lack functionality beyond tracking, such as providing personalized guidance, support through social networks, or rewarding behavior change.

- App store ratings correlate poorly with clinical utility and vary widely in terms of usability.

- Apps often do not react to dangerous information; only 23% responded appropriately when information indicated a health danger, like suicidal risk, emerged.

- Privacy policies and secure data-sharing is lacking across the range of apps studied.

To remedy these gaps, the team recommends involving clinicians and patients in the review process, tailoring recommendations based on the patient’s level of engagement, requiring crisis management standards, and requiring secure data exchange protocols.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: My paper for the California HealthCare Foundation, Digitizing the Safety Net: Health Tech Opportunities for the Underserved, looked at this very issue for digital health technologies in general (and not limited to mobile health apps). Based on my own research, I concur with the findings and recommendations of this team and laud them for addressing this important issue as mobile apps continue to proliferate but, for underserved populations, are high on the Hype Cycle.

I would go one degree further on the recommendation that providers and patients “review” apps. Users (both patients and clinicians) should be involved in the ideation and early development phase of mobile apps and digital health tools alike. This is a basic principle of user-centered design. The very people who are the end-user consumers of mHealth apps and digital health tools must communicate their needs and dreams in ethnographic research early in the process. Developers who heed this advice will do good and do well at the same time…and the gaps we see in the go-go digital health market. Furthermore, we’ve learned from many mis-steps in digital health developments of the 2000s that technology itself cannot change behaviors. A healthy (appropriately-dosed) size of “analog” human interaction can go a long way to maximizing outcomes through the adoption and use of digital health tools.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.