The Netherlands, France and Germany are the best places to be a patient, based on the Global Access to Healthcare Index, developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).

The Netherlands, France and Germany are the best places to be a patient, based on the Global Access to Healthcare Index, developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).

Throughout the world, nations wrestle with how to provide healthcare to health citizens, in the context of stretched government budgets and demand for innovative and accessible services. The Global Access to Healthcare Index gauges countries’ healthcare systems in light of peoples’ ability to access services, detailed in Global Access to Healthcare: Building Sustainable Health Systems.

The United States comes up 10th in line (tied with Spain) in this analysis.

Countries that score the highest in this index share political and financial commitment to improving access to care and a “strong civil society,” as the EIU describes these nations’ social compacts. Strong national leadership, transparency and accountability are the hallmarks in these high-performing countries.

Public investment is allocated in these top-performing nations that explicitly commit to ensuring the health of their populations. While universal coverage doesn’t guarantee universal access to healthcare services, coverage does play a central role in improving healthcare access — think of it as an on-ramp to care.

Finally, good primary care is key for good access, and ensures a sustainable healthcare system. “Experts are increasingly viewing primary care as one of the best investments governments can make at a time of strained public finances,” EIU asserts. Rafael Bengoa, who co-directs the Institute for Health & Strategy in Bilbao, Spain, and contributed to the report, notes, “you cannot meet the ‘Triple Aim’ without a good primary care set up.”

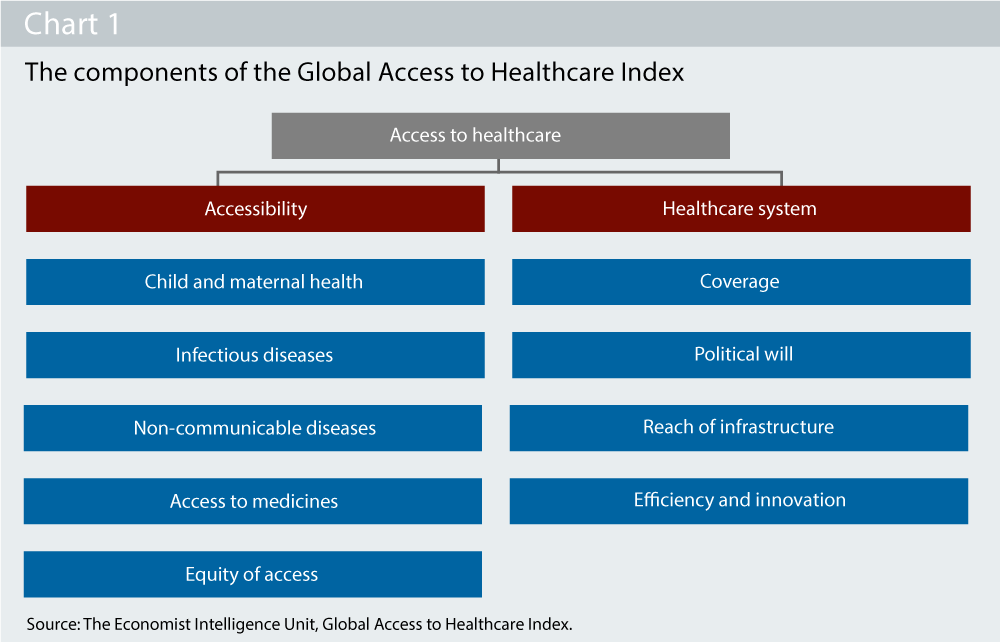

As the chart illustrates, the Index is built from two domains: accessibility and healthcare systems. Accessibility has to do with prevention and treatment services across disease areas such as child and maternal health, infectious diseases (e.g., HIV/AIDS, malaria, TV and hepatitis), and non-communicable diseases (heart, cancer, diabetes, mental health), long with access to medicines and health equity.

The healthcare system domain covers health policy, infrastructure, and institutions. Note that “political will” is explicitly called out in this methodology.

What is particularly surprising in this study is where the U.S. falls on access to medicines — below the top 10, and yet the U.S. pays higher prices for prescription drugs, overall, than any other country the world over. The top ten performing countries for access to medicines are the Netherlands, France, Germany, Australia, Italy, UK, Brazil, Romania, Israel and Thailand.

For efficiency and innovation, the U.S. also ranks lower than the first nine above us — led by Germany, France, the Netherlands, and the UK. Turkey ranks ninth, and the U.S., tenth. This category is driven by expenditures on research and development as a percentage of GDP, the existence of health technology assessment, mechanisms for identifying interventions for de-adoption (that is, suspending use of low-value technologies, drugs and services), and performance-based payment models in hospital reimbursement and primary care.

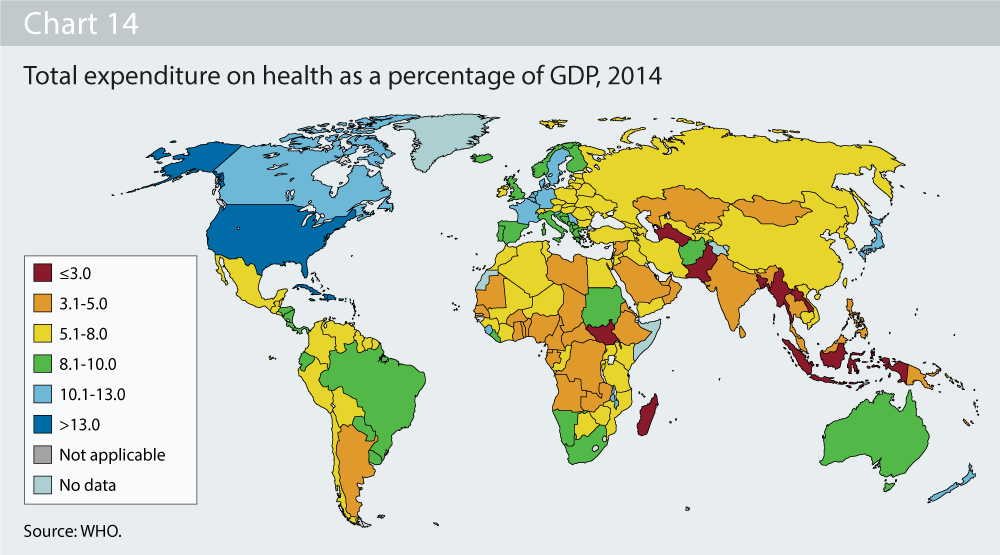

Health Populi’s Hot Points: You’re reading Health Populi and I’m a health economist, so I’ll bring this study back to healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP, shown in the map. Dark blue covers the U.S. and in this map, represents over 13% of GDP. This is actually close to 18% today — about $1 in every $5 of the national economy. That nearly-20% is also the household budget cost of care for the average American family.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: You’re reading Health Populi and I’m a health economist, so I’ll bring this study back to healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP, shown in the map. Dark blue covers the U.S. and in this map, represents over 13% of GDP. This is actually close to 18% today — about $1 in every $5 of the national economy. That nearly-20% is also the household budget cost of care for the average American family.

A critic of this Index and its methodology may argue with its construction and mix of variables. But the general results of the study are informative. The call-out of political will is timely and worth spotlighting in this moment of national U.S. healthcare reform controversy and stasis.

This begs a simple question: do Americans believe that every individual in the nation should have access to health care services, or not? In an op-ed by emergency room physician, Dr. Farzon Nahvi, observes via life-saving daily work that a free market for healthcare cannot exist…at least in the ER.

He is faced with saving lives, day after day, of people who arrive via ambulance, often waking up without realizing they were transported to the ER. “As an emergency medicine physician in a busy urban hospital, I have patients brought to me unconscious several times a day….More than once, however, such patients have regained consciousness furious. It wasn’t that they didn’t want to live — they were all simply upset at the costs their hospitalization incurred,” Dr. Nahvi explains.

He continues: “Most dismaying for me as a physician is that after all of my attempts to apply my compassion and training to save their lives…patients told me some variant of: ‘Thanks for what you’re doing, but I would rather that you hadn’t.’ [A] man with [a] brain bleed, who certainly would have died without our immediate intervention, expressed dismay. In the neurology intensive care unit, with a bolt through his skull to measure the pressure around his brain, he told me that while he did not have health insurance, he did have life insurance. He said he would rather have died and his family gotten that money than have lived and burdened them with the several-hundred-thousand-dollar bill, and likely bankruptcy, he was now stuck with.”

On March 10, 2017, House Speaker Paul Ryan said on the Hugh Hewitt radio show, “We’re going to have a free market, and you buy what you want to buy,” and if people don’t want it, “then they won’t buy it.” This doesn’t quite work in an emergency room when a provider like Dr. Nahvi has taken the Hippocratic Oath.

On March 10, 2017, House Speaker Paul Ryan said on the Hugh Hewitt radio show, “We’re going to have a free market, and you buy what you want to buy,” and if people don’t want it, “then they won’t buy it.” This doesn’t quite work in an emergency room when a provider like Dr. Nahvi has taken the Hippocratic Oath.

Do a sufficient number of members of the U.S. Senate have the political will to lay the foundation for a civil, healthy society like so many high performing nations measured by the Global Access to Healthcare Index? Might we Americans have the sort of health system where we can choose life and the pursuit of happiness instead of being financially nudged to will a life insurance policy to our loved ones, as Dr. Nahvi’s story so starkly portrayed?

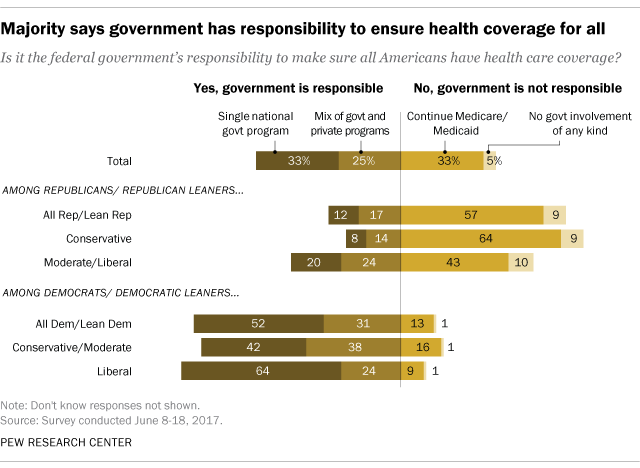

The latest Pew poll into U.S. voters’ perspectives on health reform found that 58% of all Americans see it’s the Federal government’s responsibility to make sure all Americans have health care coverage, shown in the bar chart.

Imagine a U.S. healthcare system that bolsters primary care access for all, provides a basic medicines list, and boosts spending on social care and underlying determinants of health to promote wellness and prevent illness and non-communicable diseases. These are the building blocks of a civil society and a sustainable healthcare system. There’s a direct correlation between health care quality, access, and equity. And the U.S. fails on that metric.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...