“The pandemic has shown that effective health spending is an investment, not a cost to be contained: stronger, more resilient health systems protect both populations and economies,” the OECD states in the first paragraph of the organization’s perennially-updated report, Health at a Glance 2021.

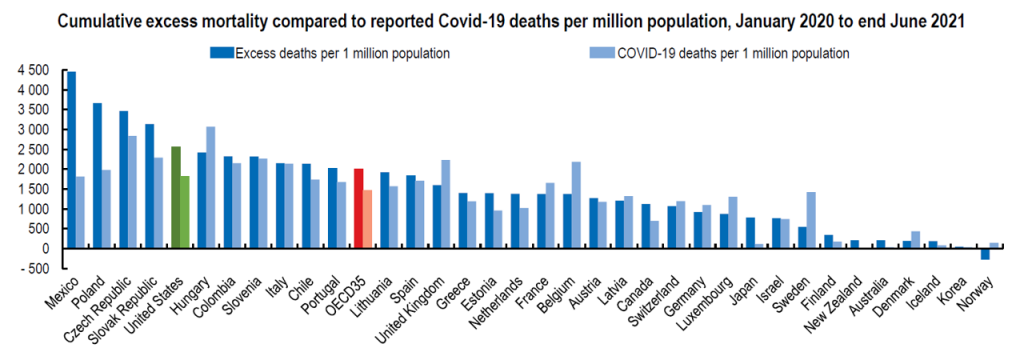

This version of the global report incorporates public health data from the “OECD35,” 35 nations from “A” to “U” (Australia to United States) quantifying excess deaths experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, the obesity epidemic, mental and behavioral health burdens, and health care spending, among many other metrics.

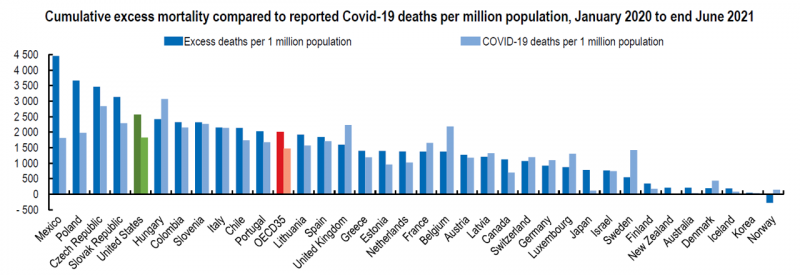

The first chart illustrates that calculation of excess deaths, which is the actual mortality experienced in each country above the expected number of deaths per 1 million people. The five countries with the highest excess death rates between January 2020 and June 2021 were found in Mexico, Poland, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic, and the United States (represented by the green bar, a rate that topped Hungary’s, Slovenia’s, Italy’s, Chile’s, and Portugal’s excess death rates, all of which exceeded the OECD35 average shown by the red bar in the chart).

In the U.S., life expectancy fell by 1.6 years, from 78/9 years in 2019 to 77.3 years in 2020.

In the U.S., life expectancy fell by 1.6 years, from 78/9 years in 2019 to 77.3 years in 2020.

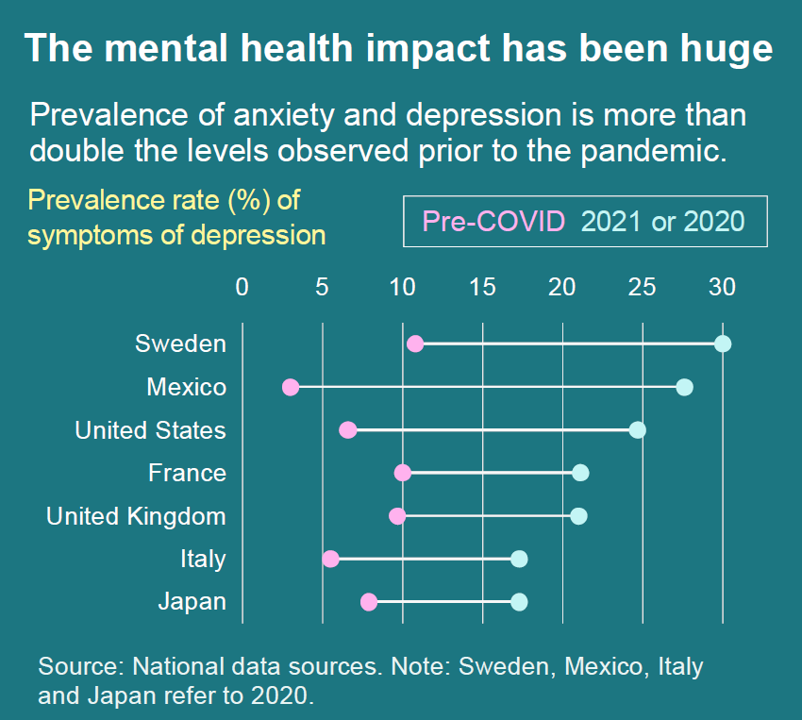

Beyond the direct deaths and morbidity associated with the coronavirus, the OECD rightly calls out the fact that “the mental health impact has been huge,” with the prevalence of anxiety and depression more than twice as much as the levels seen before the pandemic. The second chart arrays the rate of depression in seven countries including the U.S. compared with Sweden, Mexico, France, the UK, Italy, and Japan.

The prevalence of depression more than tripled to 25% in early 2021 compared with the rate in 2019.

Behavioral health impacts also hit certain people hard, such as smoking, heavily drinking, taking less exercise or activity, and as a result, gaining weight.

Smoking, harmful drinking, and obesity are three root causes of many chronic conditions, the so-called non-communicable diseases (heart, some cancers, respiratory conditions and diabetes among them).

While daily smoking rates fell in most OECD countries in the past ten years, 17% of people in OECD nations still smoke daily. Rates climbed to 25% and higher in Chile, France, Greece, Hungary and Turkey.

Obesity rates were highest in Chile, Mexico, and the United States, with obesity and overweight rates reaching 60% across the entire OECD35.

These factors also increase the risks of complications from COVID-19, the OECD reminds us in the report.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: In addition to health outcomes, mental and behavioral health statistics, and medical care utilization trends, the OECD report looked at health spending by country.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: In addition to health outcomes, mental and behavioral health statistics, and medical care utilization trends, the OECD report looked at health spending by country.

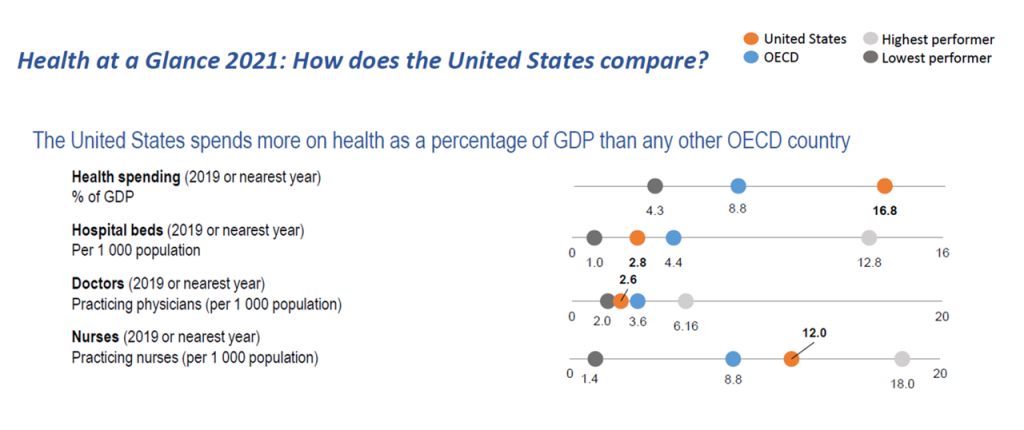

The U.S. continues to out-spend every one of the fellow OECD34 countries on a per capita and total cost basis.

The last charge graphs U.S. health care spending as a percent of GDP (some 19 cents on the national GDP dollar in America) compared with 8.8% across all OECD countries.

This high-level of spending on health care tied with a relatively low return-on-investment for health outcomes can be measured in late 2021 against the coronavirus pandemic results for the U.S. with relatively lower levels of vaccinations (despite pretty ubiquitous vaccination supply through the vast U.S. geography) and higher excess death rates than 31 of the 35 OECD nations analyzed in the report.

We return to the introductory top-line that health spending should be seen as an investment and not simply a cost input.

If the U.S. allocated spending based on an investment mentality, the investor would look holistically at patients’/health citizens’ outcomes on a life-cycle basis, from pre-natal care through to death. Through this lens, the country would allocate more resources upstream to education, childcare, clean air and water and climate change amelioration, to good food security and infrastructure for (safe, clean) transportation and broadband to all.

One of the public health economic classics I studied in school was Health As An Investment by Selma Mushkin, which she wrote in 1962,

One of the public health economic classics I studied in school was Health As An Investment by Selma Mushkin, which she wrote in 1962,

By my arithmetic, that was nearly sixty years ago.

She explained:

“Return to investment in both health and education accrue in part to the individual who makes the investment and in part to other individuals. Purchase of health services for the prevention of contagious and infectious diseases, such as smallpox, poliomyelitis, and whooping cough, benefits the community as a whole. Curative health services, such as those for the treatment of tuberculosis or syphilis, help prevent the spread of the disease; thus an individual’s purchase of services for his own care benefits his neighbors. By his improved health status and by that of his neighbors the productivity of the economy is increased.”

Selma based her reasoning on scores of studies in the economic literature, largely focused on public health spending on communicable diseases like smallpox, polio, and whooping cough.

Investing in preventing those diseases culminated in an individual’s improved health and greater productivity in the economy — for the person’s family and household, and for the larger national economy.

Sixty years later since Selma’s economic arithmetic, we still haven’t learned the simple math in the U.S. that investing in health is investing in the economy.

And, a healthier health citizen.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...