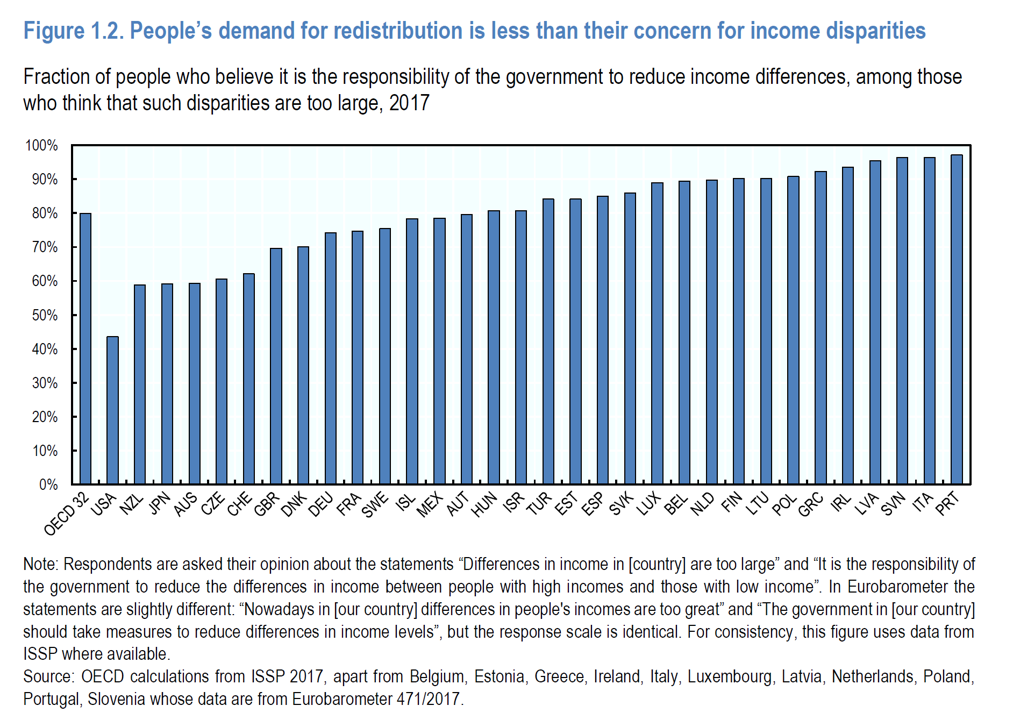

Compared with the rest of the developed world, people living in the U.S. may be concerned about income inequality, but their demand for income redistribution is the lowest among peer citizens living in 31 other OECD countries.

In their latest report, Does Inequality Matter? the OECD examines how people perceive economic disparities and social mobility across the OECD 32 (the world’s developed countries from “A” Australia to “U,” the United Kingdom).

In their latest report, Does Inequality Matter? the OECD examines how people perceive economic disparities and social mobility across the OECD 32 (the world’s developed countries from “A” Australia to “U,” the United Kingdom).

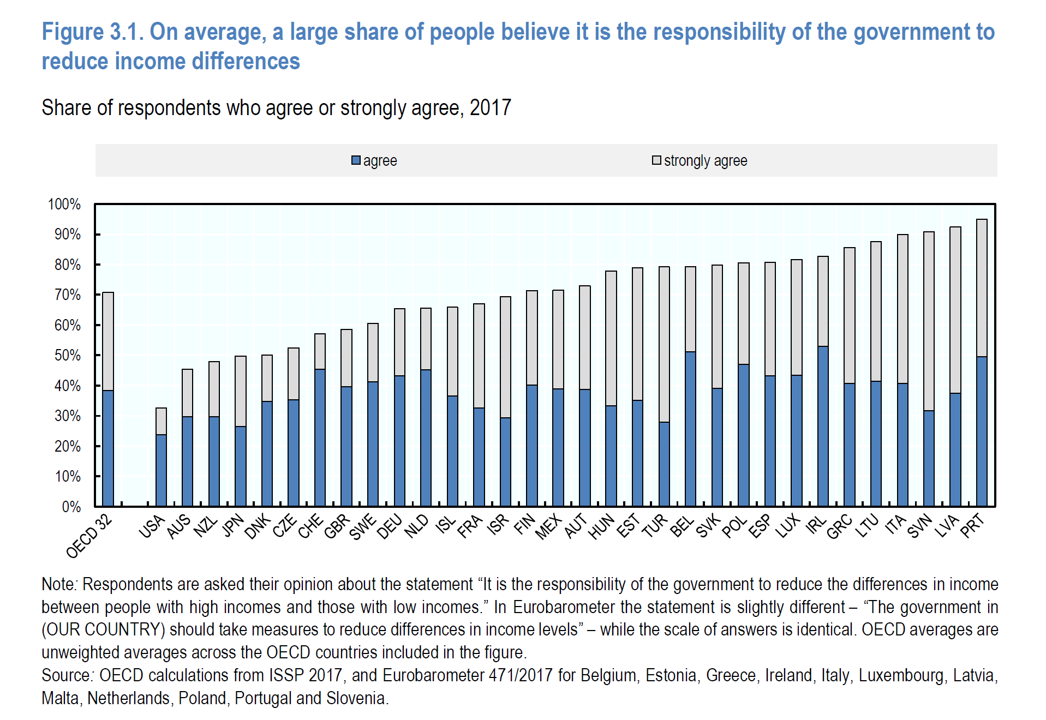

Overall the OECD 32 average fraction of people who believe it is the government’s responsibility to reduce income differences among those who think disparities are too large is 80% — that is, 4 in 5 citizens on average in each country.

In the U.S., that proportion is 40%, roughly 2 in 5 people or one-half the rate felt and found in peer nations.

The next greatest proportion of those who would look to the government to reduce income disparities is in New Zealand, Japan, Australia, the Czech Republic and Switzerland (abbreviated here as “CHE”) where 3 in 5 people view income equality to be the job of government.

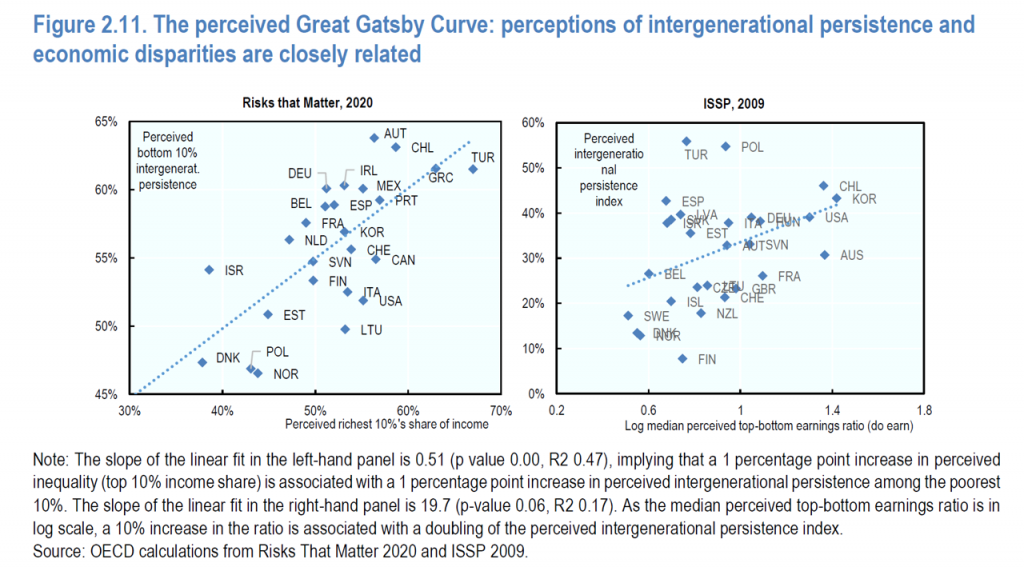

Another way to view the public’s lens on equality is how citizens look at intergenerational mobility and economic disparities.

Another way to view the public’s lens on equality is how citizens look at intergenerational mobility and economic disparities.

Economists have termed this relationship as the Great Gatsby Curve. This is the inverse relationship between income inequality and inter-generational mobility. Simply put, the curve shows that greater income inequality in one generation increases the consequences of having rich or poor parents for the economic status of the next generation.

The second graph from the report titled Figure 2.11 illustrates the Great Gatsby Curve comparing OECD countries, plotting perceptions of intergenerational persistence and economic disparities. The left-hand chart graphs data from the 2020 OECD Report Risks That Matter which shows that greater inequality spells less next-generation upward mobility: perceptions of intergenerational persistence in the shares of income of the richest and poorest 10% are closely related.

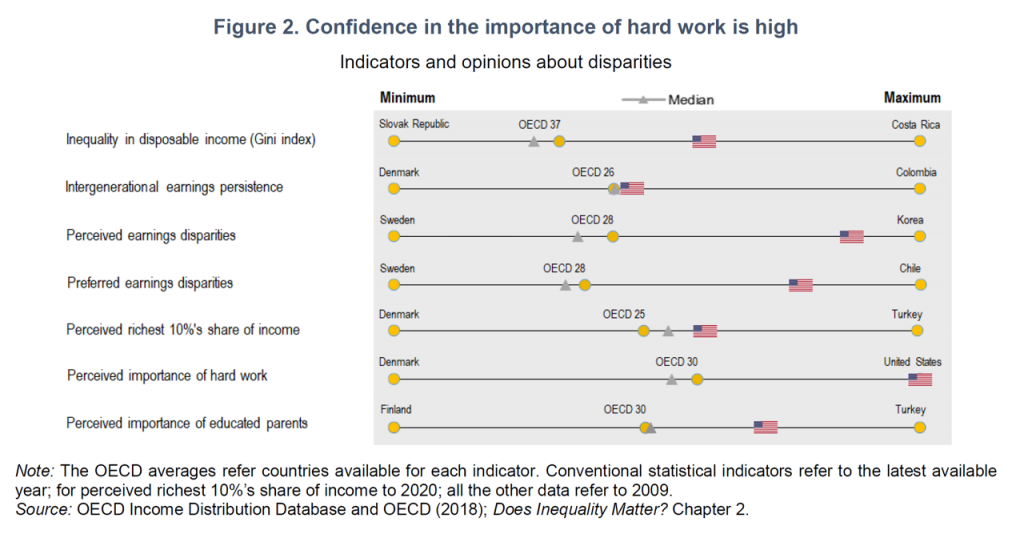

There is a third lens on equality and mobility that is particularly unique to the U.S.: that is Americans’ collective belief in the importance of hard work to get ahead in life, explained in the U.S. notes published with the Report.

There is a third lens on equality and mobility that is particularly unique to the U.S.: that is Americans’ collective belief in the importance of hard work to get ahead in life, explained in the U.S. notes published with the Report.

The chart labeled Figure 2 shows the U.S. as an outlier when it comes to “perceived importance of hard work,” compared with the OECD 30 median and Denmark residents at the opposite end of the importance-of-hard-work continuum.

Weaving together Americans’ relative lack of belief in the government’s role to redistribute income to address income disparities with this data point — the belief in hard work’s ability to move younger generations upward on the income and socio-economic ladder — the U.S. indexes higher than other OECD countries in looking to the private sector to help ameliorate economic disparities. We are already witnessing this re-shaping public health in the U.S., with the examples of CVS Health quitting tobacco, Dick’s Sporting Goods and Walmart addressing firearms safety, and grocery and discount stores providing more retail health services in consumers’ local communities.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The pandemic raised peoples’ awareness of economic disparities throughout the world, the OECD data show.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The pandemic raised peoples’ awareness of economic disparities throughout the world, the OECD data show.

I referred to the 2020 OECD Report Risks That Matter above. The subtitle of that paper was, “The Long Reach of COVID-19.”

That long reach of the coronavirus directly shaped peoples’ equality perspectives: those who reported having experienced any health or economic hardship during the pandemic themselves or in their household perceived greater inequality and intergenerational persistence than folks who did not go through a health or financial hardship due to COVID-19.

The abstract of Risks That Matter notes,

“The COVID-19 pandemic has been a global health tragedy. Yet as the world inches towards the end of the health crisis, another injury threatens to leave a more enduring scar: that of entrenched economic insecurity. The 2020 round of the OECD Risks that Matter survey presents a stark picture of economic disruption and rising worries about health and financial security across OECD countries. Despite massive government investments in social protection during the pandemic, people in most OECD countries are looking for more public support to lift them out of the crisis – and many report a willingness to pay more in taxes in order to fund better health, pensions, employment and long-term care programmes.”

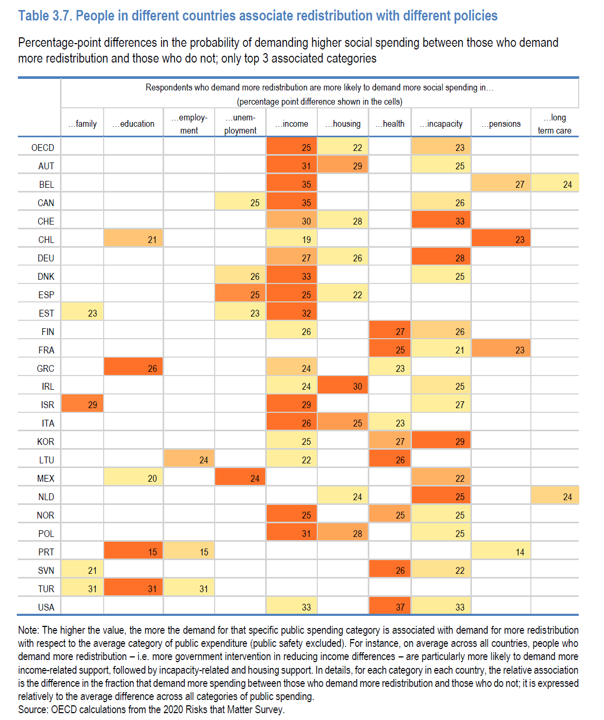

Now cast your eyes to Table 3.7 from the Inequality report. This heat-map shows us the top 3 favored social spending categories for different OECD nation’s citizens.

At the bottom of the table you’ll find the USA, whose residents rank health spending first, followed by income (in this case, favoring progressive taxation policy) and incapacity (disability).

More people in the USA cited health spending than any other citizens in the OECD family of nations.

We are left with the long-time observation — exacerbated in the pandemic — that spending on health is an investment in a nation’s economic sustainability and equality across a population — regardless of their income. The U.S. continues to be an outlier in the world of country peers.

I’ll end with a quote from Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby:

“Let us learn to show our friendship for a man when he is alive and not after he is dead.”

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...