In the organization’s annual study into physicians’ wellbeing, Medscape has diagnosed worsening burnout and depression among America’s doctors.

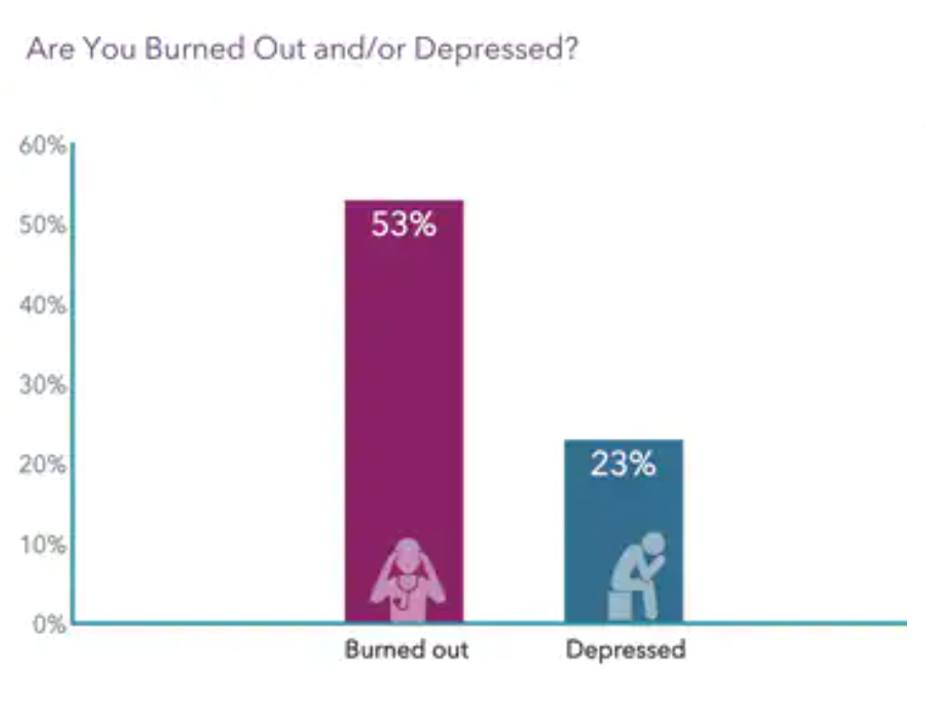

Over one-half of U.S. physicians say they are burned out or depressed, the chart from the U.S. Physician Burnout & Depression Report for 2023 calls out.

“I cry but not one cares,” is one of the represented color comments provided by one of the physicians included in the survey of 9,175 physicians polled online between June and October 2022.

The study covered 29 specialties, finding most burned out physicians worked in emergency medicine (65% saying they were burned out), internal medicine (60%), pediatrics (59%), OB/GYN (58%), infectious disease (58%), family medicine (57%), and neurology, critical care, and anaesthesiology (all at 55%).

It is safe to generalize that most physicians felt burned out by late 2022: burn out impacted physicians in public health and prevention, pathology, cardiology, nephrology and other specialties but still hit at least 37% of practicing doctors in those fields.

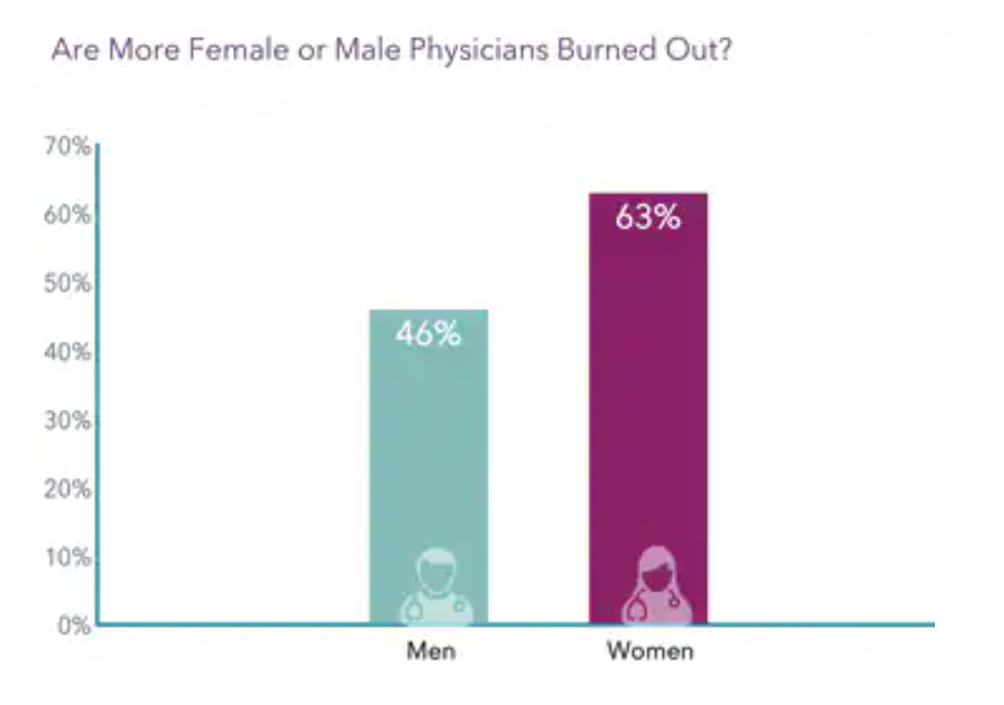

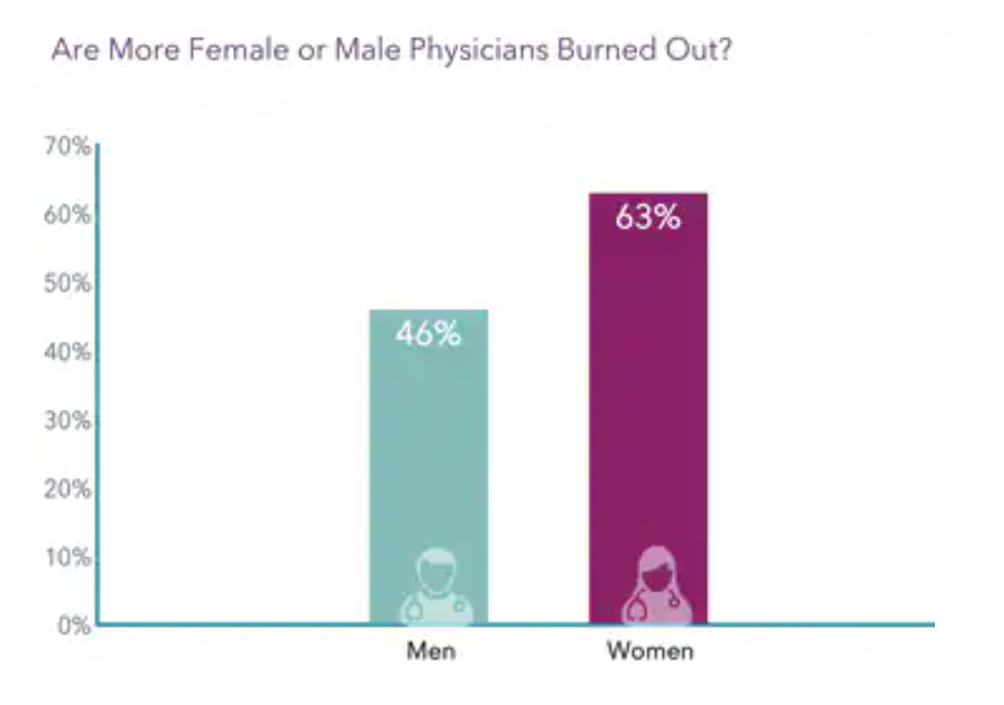

Nearly two-thirds of female physicians felt burned out compared with 46% of males, the second chart shows.

Other key statistics in this study were that:

- 30% of doctors said they felt burned out for at least 2 years

- Physicians feel burnout across practice settings, from outpatient clinic and ambulatory care to hospital-based sites

- Only 13% of physicians have sought professional help to reduce their burnout, with another 47% saying they would consider seeking support.

But only 45% of doctors said their workplaces offered programs addressing physicians.

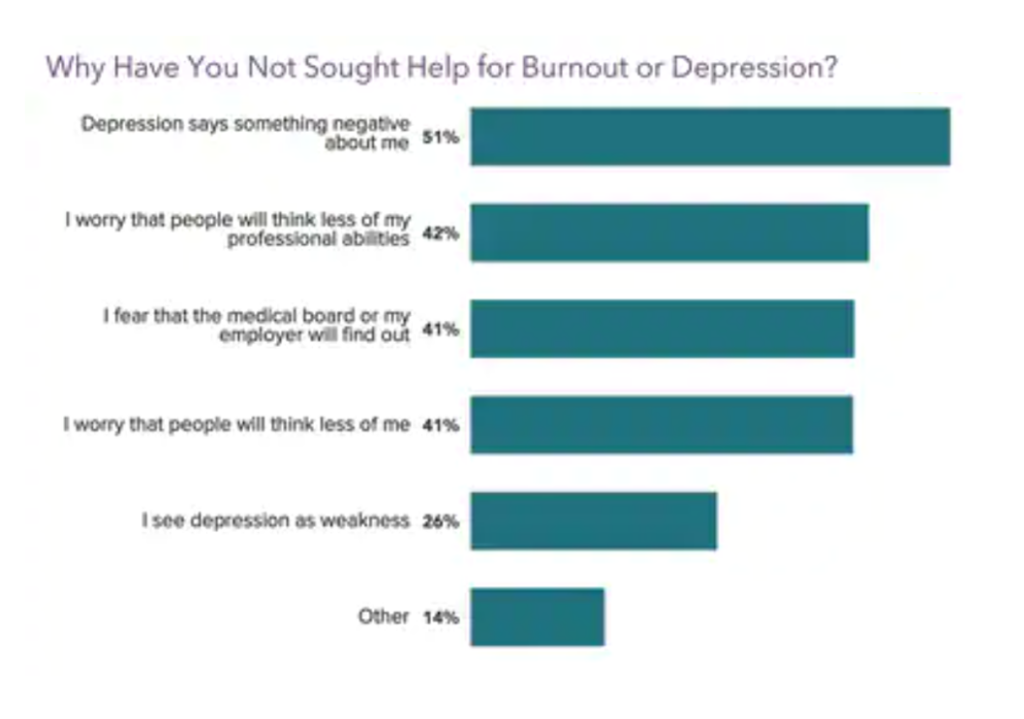

So why haven’t more doctors sought help for burnout or depression? One in two doctors said it was because “depression says something negative about me” (51%).

What contributed most to burnout, physicians said, were too many bureaucratic tasks (61%), lack of respect from coworkers (38%), too many workhours (37%), and insufficient compensation (34%).

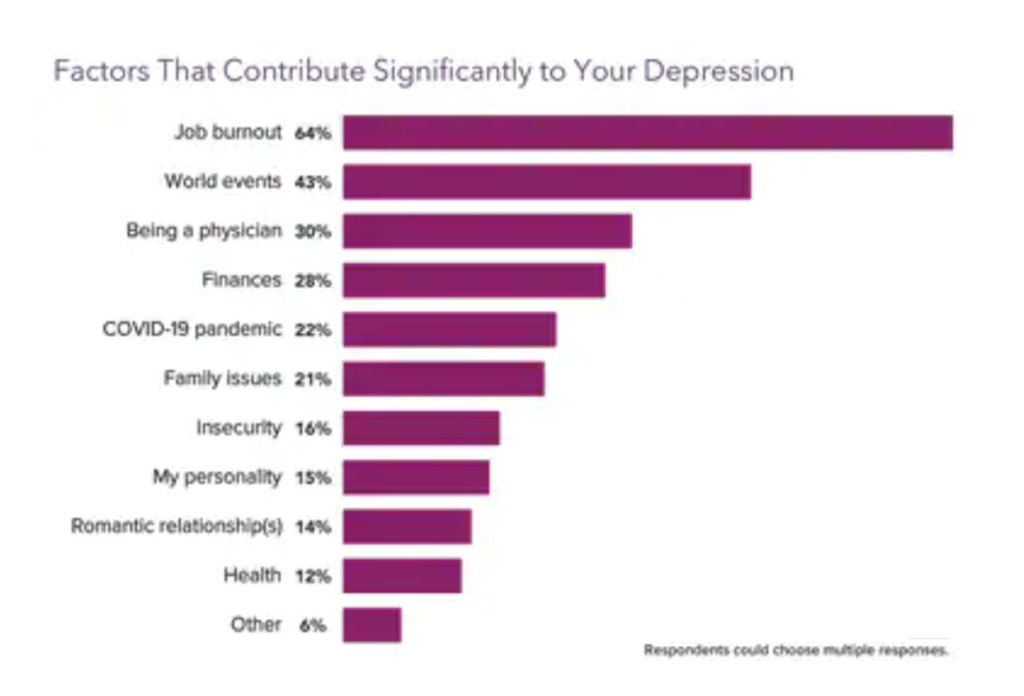

Key factors contributing to depression was first burnout (see previous paragraph!, for 64% of the physicians), world events (43%), and simply put, “being a physician.”

Physicians cope first and foremost through exercise and physical activity (for 50% of people), talking with family or friends (43%), sleeping (41%), spending time alone (40%), listening to music (37%), and eating junk food (32%).

22% of the doctors said they drank alcohol to address burnout, with the same percentage meditating.

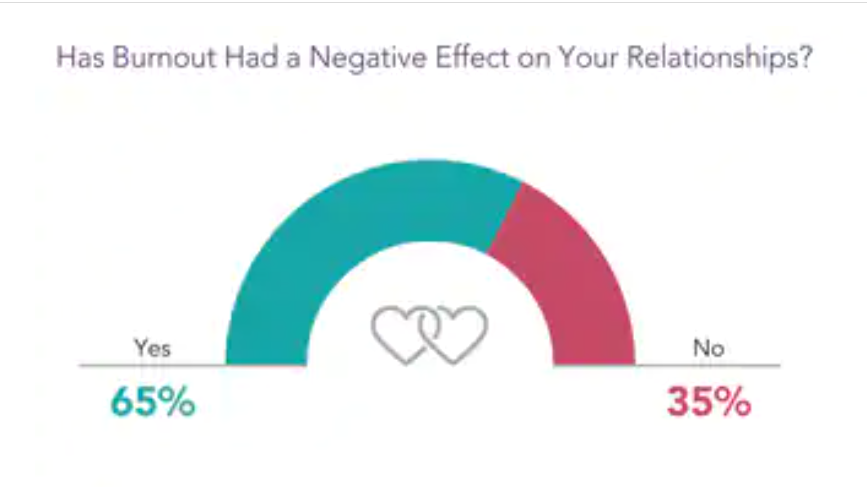

Unsurprisingly and sadly, two-thirds of physicians said burnout had a negative effect on relationships.

And that impact goes beyond romantic attachments: one in two doctors said that depression affected their patient relationships in several ways: become easily exasperated, being less careful when taking patient notes, expressing frustration, and making “uncharacteristic” errors.

Heath Populi’s Hot Points: When asked why they haven’t yet sought help for burnout or depression, one-half of the doctors believe that “depression says something negative about me.”

In addition, 42% worried that people would think less of their professional abilities, closely followed by concerns that the medical board or their employer would find out about the mental health issue or think less of them as a result of knowing.

“I cry but no one cares” coins the desperation too many physicians feel when it comes to their personal states of burnout and depression.

Staying closeted about their mental health — due to concerns about professional or employers’ opinions — exacerbates the problem in terms of seeking support and sustaining the stigma that is too-often associated with being open about mental health concerns.

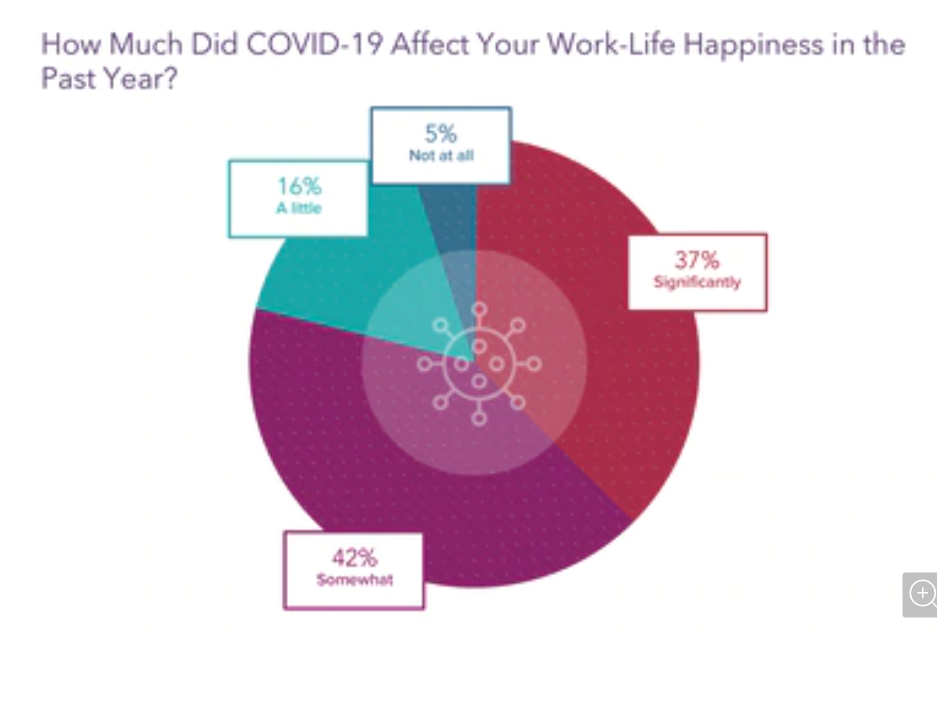

Medscape has been tracking U.S. physicians’ states of burnout and depression for many years. In 2023, the study asked how much COVID-19 affected peoples’ work-life happiness in the past year, a new factor that is also impacting clinicians’ well-being beyond bureaucracy, lack of autonomy, and pay, is indeed COVID-19.

Four in 5 physicians believe COVID-19 negatively impacted their work-life happiness, with over one-third believe it has been a “significant” impact on happiness.

From the early days of the pandemic in 2020, I pointed to two toxic side effects of the coronavirus beyond the virus itself: those were financial stress and mental health impacts.

Here in our precious physician human capital, we see that quite clearly re-shaping clinicians’ hearts and minds in negative ways.

We turn to the north star of the Quintuple Aim to remind us of what’s important about re-forming health care: improving health outcomes, delivering a better experience, lowering per-patient costs, addressing health equity and the fifth pillar: bolstering the well-being of clinicians.

Medscape reminds us once again that physicians are in pain.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...