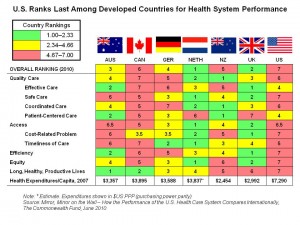

Among seven developed countries – Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States of America — it’s the U.S. that ranks dead last in the effectiveness of the nation’s health system. In particular, the U.S. rates poorly on the issues of coordination of health care, cost-related problems causing access challenges for health citizens, efficiency, equity, and long/healthy/productive lives for citizens.

Among seven developed countries – Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States of America — it’s the U.S. that ranks dead last in the effectiveness of the nation’s health system. In particular, the U.S. rates poorly on the issues of coordination of health care, cost-related problems causing access challenges for health citizens, efficiency, equity, and long/healthy/productive lives for citizens.

Of course, it also figures in that the U.S. spends more per capita on health care than any other country on the planet: $7,290 per person compared with Health Nation #1, the Netherlands, which spent $3,837 dollars per Dutch person in 2007.

The Commonwealth Fund has been ranking health systems since 2004 in its reports titled Mirror, Mirror published in 2004, 2006, 2007 and now in June 2010. This latest version echoes the previous years’ rankings of the U.S. in seventh place based on several criteria:

- Quality of care, rated on effectiveness, safety, coordination, and patient-centeredness

- Access, in terms of cost-related problems and timeliness of care

- Efficiency

- Equity

- Long, healthy, productive lives for health citizens (measured in terms of mortality amenable to health care, infant mortality, and health life expectancy at age 60)

- Health expenditures per capita (based on 2007 data from the OECD).

The best the U.S. does, vis-à-vis the 6 competitors in this health effectiveness race, is in the area of effective care and patient-centered care, where the nation ranks #4 — mid-pack.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: “It is difficult to disentangle the effects of health insurance coverage from the quality of care experiences reported by U.S. patients. Comprehensiveness of insurance and stability of coverage are likely to play a role in patients’ access to care and interactions with physicians,” the report observes.

The fact that the U.S. health insurance system is based on employer-sponsorship, and that tens of millions of Americans aren’t covered by any sort of plan, plays heavily into the nation’s poor ranking in this study. Even with insurance coverage, though, there are numerous and troubling access problems for health citizens in the U.S. system: the most prominent of these is cost, where out-of-pocket spending can prevent both sick and well people from getting care they need — either to access care for an existing condition (whether acute illnesses like cancer, where cost has been found to lead to some self-rationing) or for well visits.

Health citizens in other developed countries have regular physicians and better continuity of care. This points to the need for some type of medical home that all U.S. health citizens can count on. The U.S. spends more than enough on health care per capita. But the ‘capita’ doesn’t extend to every health citizen. Nor is the money being spent with a keen eye on the art of health benefit design, health care workflow, and health citizens’ usability.

The intersection of “art” and the U.S. health system brings to mind a quote from Elie Wiesel, the 1986 winner of the Nobel Peace Prize: “The opposite of art is not ugliness; it’s indifference.” When it comes to the art of health system design, the Netherlands is the Van Gogh of health care. In the U.S., it’s the land of health access and equity indifference.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.