The good news that was packaged in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), that is, health reform, was that millions of uninsured Americans would receive health insurance coverage through the Medicaid program. But insurance doesn’t equal access; there’s a limiting factor that’s a formidable obstacle in many of these millions of newly-insured people getting care: the physician supply in the U.S., which varies from region to region of the U.S.

The good news that was packaged in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), that is, health reform, was that millions of uninsured Americans would receive health insurance coverage through the Medicaid program. But insurance doesn’t equal access; there’s a limiting factor that’s a formidable obstacle in many of these millions of newly-insured people getting care: the physician supply in the U.S., which varies from region to region of the U.S.

There’s both a quantitative aspect to this challenge along with a qualitative one. The U.S. has long had a maldistribution of physicians in both urban cores and rural towns; that’s the quantitative challenge. The other aspect that diminishes physician supply for newly-insured people on Medicaid is that fewer doctors accept Medicaid patients compared to commercially insured people and Medicare enrollees.

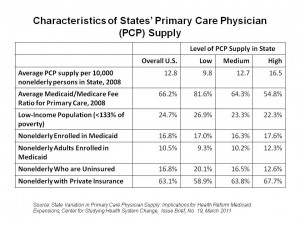

The Center for Studying Health System Change analyzed findings from their 2008 Health Tracking PhysicIan Survey, a national poll of over 4,700 U.S. physicians with a 62% response rate.

The study found that primary care physician (PCP) supply varies a lot from state to state. In particular, the southeastern U.S. (except for Florida) and the mountain states have a lower proportion of PCPs per 10,000 people than other regions in the U.S. In addition, Indiana and Kentucky are in the lowest tier of PCP access per 10,000 people. The “richest” PCP supply region is the northeastern U.S.

Combining these numbers with the percentage of PCPs who accept Medicaid shows that Medicaid PCP supply is 1.7 times greater in high-supply states vs. low-supply states. This calculation included both adult (non-elderly) and child enrollees. The difference lessened when taking out children and pediatricians from the analysis.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The bottom line in this study is that Medicaid PCP supply will likely increase the most in states that already have greater PCP supply vis-a-vis the Medicaid population. And shortages of PCPs for Medicaid enrollees will likely increase even more in states that already have low Medicaid PCP supply.

While PPACA provides for a short-term increase in Medicaid reimbursement rates for PCPs, the CSHSC expects that this will not improve the Medicaid PCP supply in the low-PCP states. These states already have high uninsured rates and will have the greatest enrollment increases and demand for care.

There will need to be a re-working of physician compensation to attract new PCPs who will accept Medicaid enrollees, in the form of pay for performance and accountable care models — where physicians could be more highly compensated for providing medical homes for newly insured patients.

Governors universally vented at the February 2011 meeting of the National Governors Association, looking for flexibility in Medicaid as deficits persist for most states. This declining fiscal picture is due to declining tax revenues , increasing demand for services (most particularly health/Medicaid and education), and crises in state public pension funds. Governors and their staffs who deal with health will need to become expert artisans in the creative re-working of care delivery for patients enrolled in Medicaid.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.