Activity and sleep trackers hold promise for the health and wellbeing of people over 50. But they’ve miles to go before their design and usefulness get props from older people.

The AARP’s Project Catalyst report, Building a Better Tracker: Older Consumers Weigh in On Activity and Sleep Monitoring Devices, presents research conducted with Georgia Tech’s Home Lab which gave 92 people a digital wearable to track activity or sleep over a six week period. The second graphic shows the devices used in the study.

3 in 4 of the activity![]() tracking users said their devices were, or had the potential to be, useful. One-half reported feeling increased motivation for healthier living, and said they were more active, slept better, or ate more healthfully. People especially enjoyed learning about their personal activity and sleep patterns, receiving motivation by seeing progress made toward a goal, confirming current activity levels, and finding the device easy to use — when it was so.

tracking users said their devices were, or had the potential to be, useful. One-half reported feeling increased motivation for healthier living, and said they were more active, slept better, or ate more healthfully. People especially enjoyed learning about their personal activity and sleep patterns, receiving motivation by seeing progress made toward a goal, confirming current activity levels, and finding the device easy to use — when it was so.

The bottom line: 42% of the study participants said they planned to continue to use a wearable activity device in the future.

But older people are not unlike younger people in one major respect: many discontinued use before the end of the study, citing inaccuracies in data generated by the device, challenges in the instructions, syncing problems, and difficult in wearing the device (namely, discomfort).

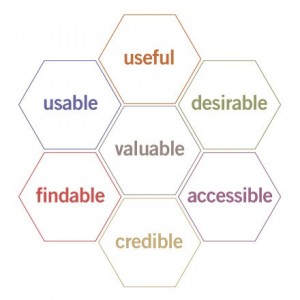

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The third graphic illustrates Peter Morville’s honeycomb for user experience design, the facets that must be considered when putting a product or service into a consumer’s hands and life.

The mindset of the older user in AARP’s study was that they exercise, first and foremost, for positive health — rated higher than avoiding illness, staying nimble, staying strong, or losing weight. With “positive health” top-of-mind for a consumer, there’s some goodwill from the start of adopting a digital activity tracker (especially true among women in the study). This positive-health mindset is also a central thesis in the book No Sweat by Dr. Michelle Segar, whose work focuses on motivating people to see exercise as a real-time gift we give ourselves.

The negative experience of a frustrating set of instructions, or itchy wristband, or device malfunction can quickly erode that goodwill, which impacts people under 50 as well and leads to abandonment of devices.

The seven honeycomb elements are all integral to a user’s perceptions on any new product or service. For activity tracking in health, they’re especially important because of the potential upside for personal wellness and quality of life. In health, several of these issues are major deal-breakers for a consumer:

- Credibility – Can I trust the data that’s emanating out of the device? Can I trust where that data might be stored and shared?

- Accessibility – Are features easy to use? Consider mobility and aging challenges, such as arthritic joints and vision correction.

- Findability – Is the content easy to navigate? Are instructions clear, simple, and straightforward?

The over-arching answer to the questions is…design for the user. This isn’t a new answer, but the concept continues to challenge many of the most popular devices on the market available via mass merchants.

Note that the #1 factor that would guide an older person’s near-time purchase of an activity/sleep tracker is user reviews, above consulting with a health professional or talking with family and friends. Health is social, and good design, a beautiful viral thing.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...