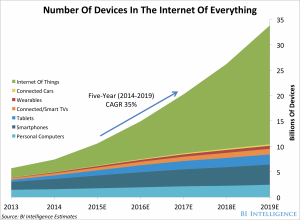

By 2020, according to the World Economic Forum, more than 5 billion people and 30 billion “things” will be connected to the Internet — cars, refrigerators, TVs, washing machines and coffeemakers, among those 5 bn folks’ electronic stuff.

By 2020, according to the World Economic Forum, more than 5 billion people and 30 billion “things” will be connected to the Internet — cars, refrigerators, TVs, washing machines and coffeemakers, among those 5 bn folks’ electronic stuff.

But so will medical devices, activity trackers, and a host of sensor-enabled “things” to help people and clinicians optimize health and manage illness.

The Internet of Things (IoT) phenomenon, which is already penetrating households with energy management and security applications, is reaching health care. One of the pioneers in this connected health market is Dr. Joseph Kvedar, who leads the Center for Connected Health, part of Partners Healthcare in Boston.

For two decades, Joe’s team at the Center has undertaken research “connecting” patients with clinicians to assess what works in linking people with digital tools that enable self-care outside of the doctor’s office and hospital, and in the person’s home, workplace, or on-the-go.

Six years ago, I featured such a patient that connected health while driving a truck on the road; David Jessee connected to the Cleveland Clinic via a blood pressure monitor linked via a laptop computer to Microsoft HealthVault, managing hypertension over his long haul truck route. See my report, Participatory Health: Online and Mobile Tools Help Chronically Ill Manage Their Care, published by the California HealthCare Foundation in 2009, to read about Jessee’s successful self-care regimen through connected health.

How time flies when you’re researching and gathering evidence for connected health, Dr. Kvedar has found. Since David Jessee’s 2009 story, Apple’s iPhone, Fitbit, and the Qualcomm Life 2net platform, have come onto the market as new-new things, and sensors have become cheaper and smaller. Smartphones are fairly ubiquitous among most people, increasingly replacing texting phones. That mobile phone, expanding broadband, and people taking on Do-It-Yourself (DIY) life-flows are driving adoption of personal electronics.

Early adopters of personal health technologies have been fitness buffs and Quantified Selfers, Joe writes; these are people who fall outside of the “not so fit and fabulous crowd,” as he puts it, meaning the mass middle (with ever-expanding middles, if you will).

Selling health to the mass of consumers is difficult, to both people (patients, consumers) and to the front-line workers in health care: physicians, providers, hospital administrators all.

There’s a shake-up a-comin’, Joe writes, a new reality that is the migration in health care payment from volume-to-value, from fee-for-service to paying-for-performance. Depending on the local healthcare market you’re looking at, this is slow in coming, but remember what founder of Institute for the Future, Roy Amara, said first which is often coined today as “Amara’s Law:” “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

And so it is with the current morphing health care payment environment. There is momentum which is realigning incentives for employers covering health insurance, payors sponsoring health plans (like government and unions), suppliers to the industry (such as pharma and medical device firms), providers and — most directly impacted — patients, who are in the throes of becoming consumers in so-called consumer-directed health plans.

Regarding patients, as John Moore, CEO of Twine Health, is quoted, “You can’t educate people to better health. You have to engage them and support them in learning it for themselves.”

What will underpin moving from Healthcare 1.0 to the new-new health care delivery, featuring a heavy dose of self-care as noted by John Moore, is “the digital Rx,” the right combination of digital + health care + self care. The connectivity of “things” which people use every day — notably their phones and, increasingly, cars, TVs, kitchen appliances, bathroom objects (THINK: WiFi-enabled scales) — will seamlessly, invisibly collect data about “us,” feed those datapoints into algorithms, be analyzed for personal and professional advice, and feedback to patients and clinicians in a cycle that informs and motivates individual and collective health decisions.

The Internet of Health Things is a book that lays out the reality of consumer-directed health in its real definition: how people will be empowered by technology (broadly, the IoT) and incentives to self-care, engage in more shared-decision making with clinicians, and become more effective health care consumers, patients and caregivers. Read it, and get smarter on the IoT for health.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: As we approach January 2016, the annual Consumer Electronics Show is upon us, there Dr. Kvedar will be signing his book for the larger business community beyond those in digital health. The new smart TVs, connected fridge’s, energy-knowing washers, and Bluetooth-enabled autos will be on display. So will the ever-growing digital health space, which in 2016 will feature more than wristbands and WiFi scales: look for Honeywell to expand its concept of home security to health, for earbuds to gauge heart health while exercising, and for smart water bottles to nudge us to hydrate. The Internet of Healthy Things will become more real in 2016.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: As we approach January 2016, the annual Consumer Electronics Show is upon us, there Dr. Kvedar will be signing his book for the larger business community beyond those in digital health. The new smart TVs, connected fridge’s, energy-knowing washers, and Bluetooth-enabled autos will be on display. So will the ever-growing digital health space, which in 2016 will feature more than wristbands and WiFi scales: look for Honeywell to expand its concept of home security to health, for earbuds to gauge heart health while exercising, and for smart water bottles to nudge us to hydrate. The Internet of Healthy Things will become more real in 2016.

For my take on CES 2015 and “health, everywhere,” and how even Whirlpool “cares,” here was my take just about one year ago.

Welcome to the Internet of Everything, where health is Everywhere.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...