States that expanded Medicaid since the start of the Affordable Care Act made greater health system access improvements than those States that did not expand Medicaid, according to Aiming Higher: Results from the Commonwealth Fund Scorecard on State Health System Performance.

There’s good news and bad news in this report: on the upside, nearly all states saw health improvements between 2013 and 2015, and in particular, for treatment quality and patient safety. Patient re-admissions to hospitals also fell in many states.

But on the downside, premature deaths increased in nearly two-thirds of states, a reversal in the (improving) national mortality trend. In addition, health disparities among vulnerable populations also persisted and worsened in certain states.

The study assesses states’ performance on over 40 measures in five areas:

- Health care access

- Quality

- Avoidable hospital use and costs

- Health outcomes

- Health care equity.

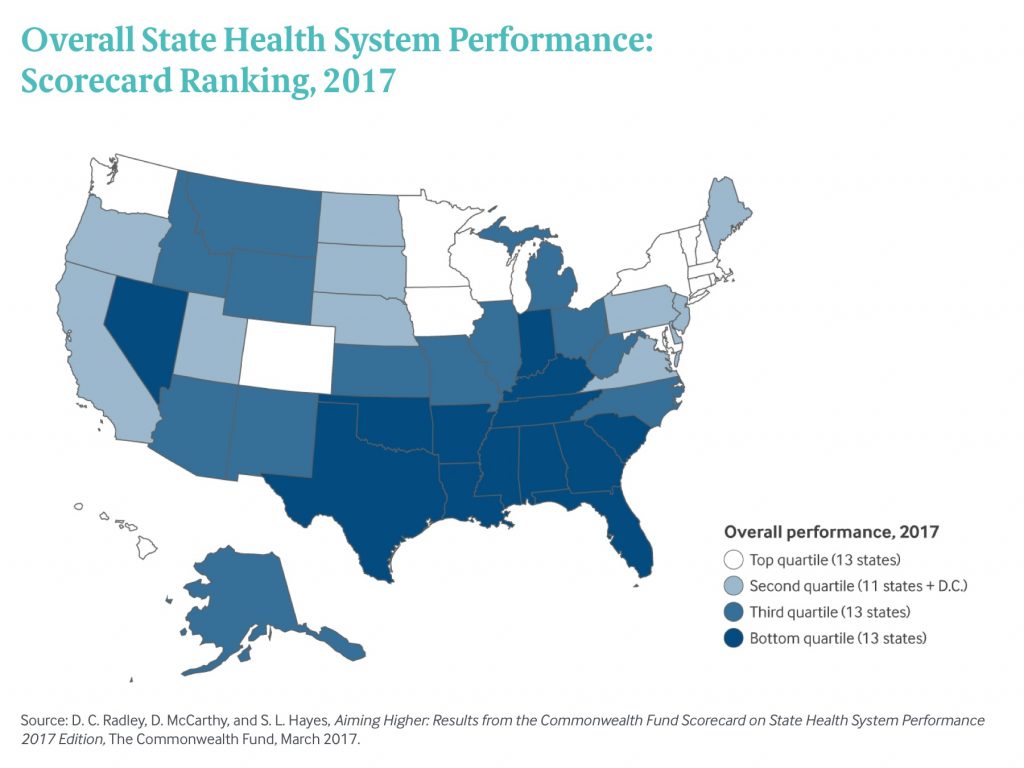

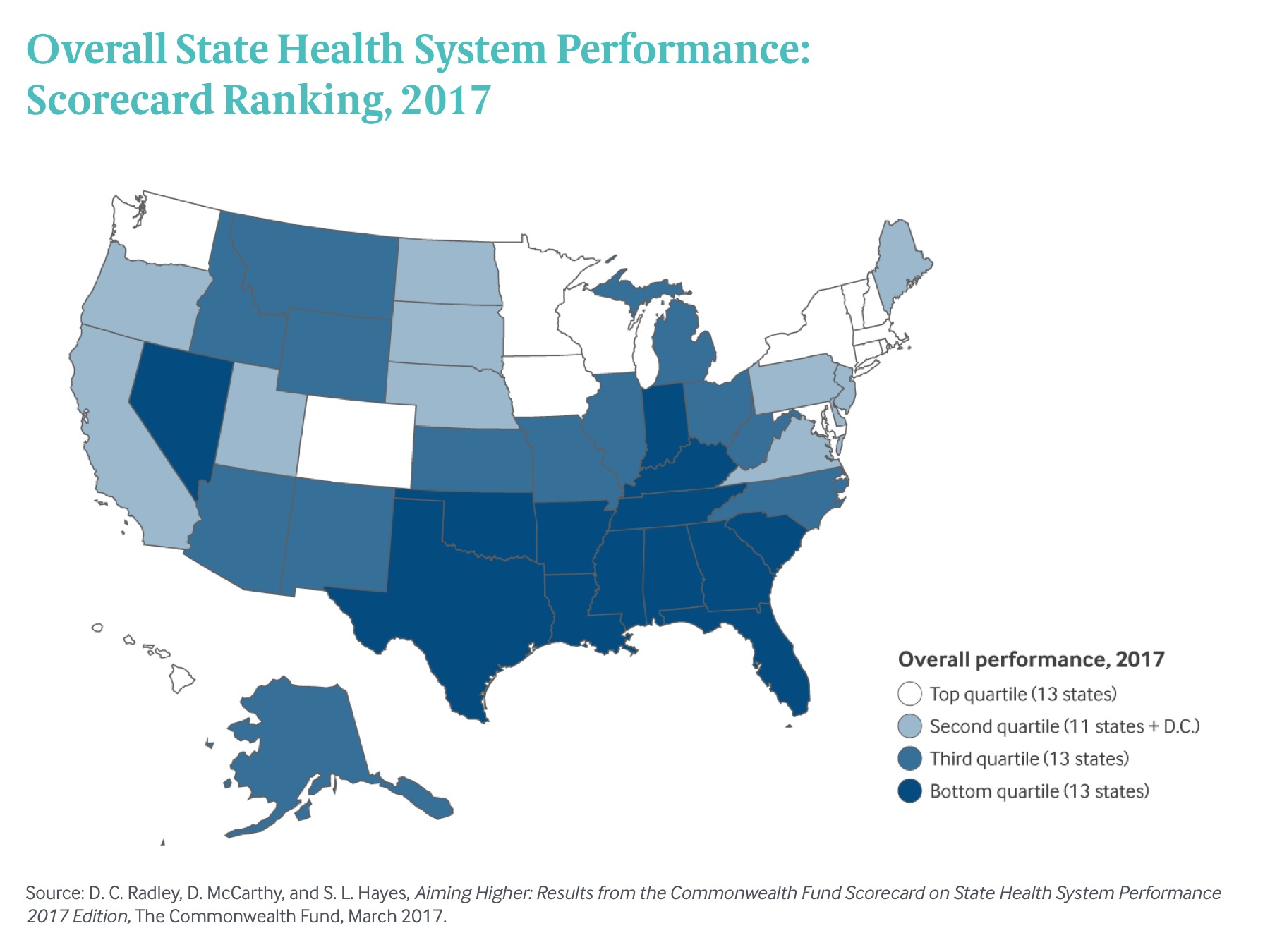

The map illustrates the four quartiles of performance, from top (13 states, tending to be in the north) to the bottom (13 states, tending to be in the south).

The top-performing healthcare states were Vermont, Minnesota, Hawaii, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Colorado, Iowa, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Washington State.

The lowest-quartile of states’ healthcare performance included Florida, Kentucky, Georgia, South Carolina, Texas, Indiana, Tennessee, Nevada, Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and at the bottom position #51, Mississippi.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Maps tell stories, and this map from the Commonwealth Fund study matches up with other maps we’ve recently featured in Health Populi (this link, a post on broadband as a social determinant of health). Where positive inputs on social determinants of health are lacking, health outcomes tend to lag and disparities emerge.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Maps tell stories, and this map from the Commonwealth Fund study matches up with other maps we’ve recently featured in Health Populi (this link, a post on broadband as a social determinant of health). Where positive inputs on social determinants of health are lacking, health outcomes tend to lag and disparities emerge.

“The implementation of the Affordable Care Act’s major coverage expansions in 2014 led to a sharp reversal in [these] access trends,” The Commonwealth Fund notes. Medicaid expansion and other access programs worked to improve care in a majority of states. Research shows that people with health insurance cover are more likely to have a usual source of healthcare and have had a recent health care visit.

This access is attributable most to primary care, which is linked to earlier disease detection and greater adherence to treatment regimens (e.g., prescription medicines, physical therapy, etc.). Primary care is a necessary, but not sufficient, ingredient in the recipe for individual, population, and public health. But it certainly helps, as the U.S. peers making up the OECD nations’ health systems can attest. Our wealthy nation-colleagues have much stronger primary care backbones than America’s, and they spend far less money on healthcare services. What they do spend more on than the U.S., however, is social care.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...