Most consumers access the Internet for health information before they ask their doctor for the same information. But virtually everyone who goes online for health information would trust a website recommended to them by their doctor, according to the dotHealth Consumer Health Online – 2017 Research Report.

This survey was conducted on behalf of dotHealth, an internet registry company channeling “.health” domains to organizations in the broad health and healthcare landscape. [FYI, both Health Populi and JaneSarasohnKahn are also registered with .health domains, having availed ourselves of this service at launch].

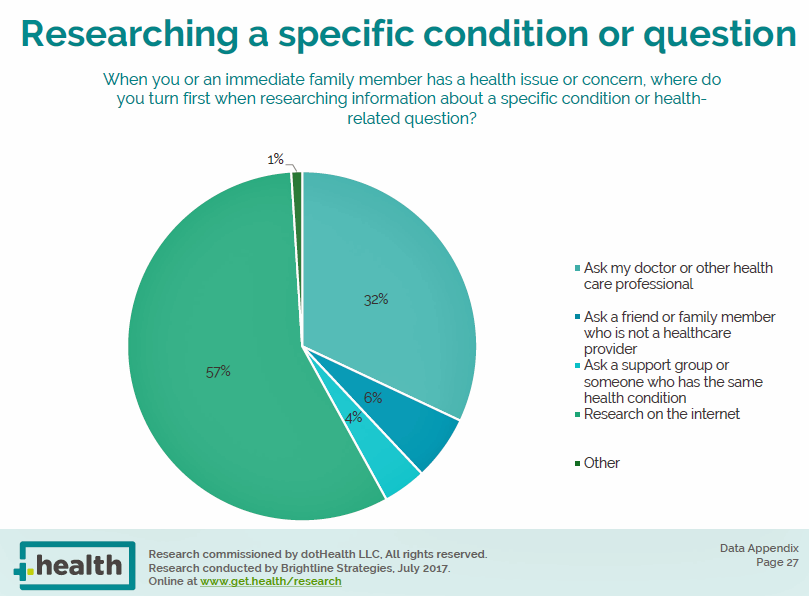

Six in 10 consumers who have used the internet in the past year for health reasons did research on the internet for an immediate health issue first before asking a healthcare provider that question, shown in the first chart.

47% of health-internet info seekers used a laptop of desktop computer for their searchers, and 44% of people used a mobile device for their searches (via smartphone or tablet), at least weekly.

Among all sources that people trust to recommend health related websites, the most-trusted by far are personal physicians and hospitals, followed by friends and family. Government or public health agencies place 3rd on the health website trust roster, followed by in-person and online support groups. Consumer health product companies are trusted on-par with support groups (with a mean trust score of 5.4 for consumer health companies versus 5.5 for the support groups). Pharma and medical device companies rank last on this trust-list.

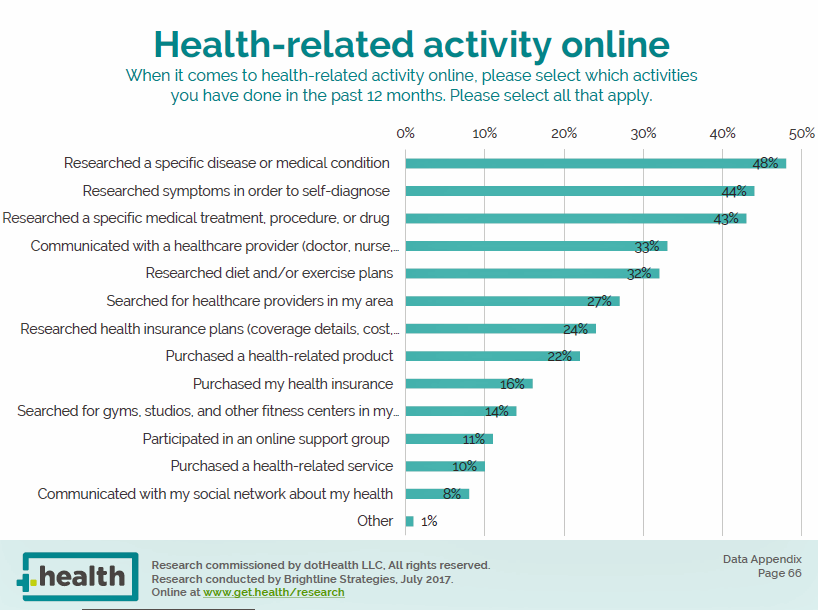

Once online, health info seekers’ most popular activities include 3 types of researching: on specific conditions; on symptoms to self-diagnose; and, for specific treatments, procedures, or drugs. These are all self-healthcare tasks. Down the list are some health administrative activities, like communicating with and seeking providers. A third category of online health activity is financial: shopping for and buying health plans, purchasing health related products, and buying health services.

One of the most exciting findings in this study is that older health consumers are active in seeking health information online. Once part of the digital health divide, older U.S. patients have grown information and internet-savvy over the years. Fully 2 in 3 health internet users 65 and over viewed medical results online, dotHealth found.

Another population typically digitally under-served by the U.S. healthcare system are people earning lower incomes. In this study, 45% of people earning under $25K a year sought health information online via a smartphone or tablet. This percentage is higher than that for people earning more money in several higher income segments, including for those earning over $125,000 a year. For people with lower incomes, access to health information online can help to supplement (not substitute) primary care access. [For more on people with lower-incomes who are at-risk to self-ration health care due to cost, see the post, 1 in 3 Americans Still Self-Rations Healthcare.]

The report is based on a survey among 1,509 U.S. adults 18 and over, conducted in June 2017.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: When we wrote our report on the role of the Internet in health care for California Healthcare Foundation in the year 2000, Health e-People: The Online Consumer Experience, Mary Cain, Jennifer Wayne and I explored the Internet as a new-new thing in healthcare. In that five-year forecast, we identified three barriers which were limiting certain consumers’ use of the Internet for health and healthcare: privacy concerns, the Digital Health Divide among poor, minority, and older people; and, health care as “high touch” – that the kinds of health services that could be offered online would be limited.

Looking back, that 5-year crystal ball did a good job foreseeing the short-term future of online healthcare and its limitations.

17 years later, these three major obstacles have new wrinkles to consider. Privacy, still a concern, has different implications: consumers are much more aware of security issues in the post-Equifax and -Snowden era. Yet consumers who use technology for daily personal work- and life-flows are also getting more comfortable in health information sharing when people perceive a value-based tradeoff for that personal information, as well as a feeling of data altruism and a sense of paying-if-forward when sharing data on serious illnesses people are facing.

The digital health divide is being addressed through the proliferation of smart phones being adopted across the income spectrum. Consider that the hardware platform, though, because lower-income and rural consumers’ access to data plans and broadband is still compromised. Thus, the digital health divide remains in many geographies due to lack of connectivity — which I contend is a modern-day social determinant of health, which I addressed in the Huffington Post in July 2016.

Finally, let’s address the issue of “high touch” health care. Today, telehealth is being adopted quickly after a slow ramping up over the past decade. Most employers have baked in telehealth benefits into health plans, seen as an opportunity to bend corporate healthcare cost curves when part of value-based benefit designs. Telehealth reimbursement is also a growing practice among some managed care plans. And consumers, eager to access just-in-time care in convenient times and places (like home and workspaces), have begun to open their wallets to pay for telehealth consultations (for both physical care and mental health) out-of-pocket.

Finally, let’s address the issue of “high touch” health care. Today, telehealth is being adopted quickly after a slow ramping up over the past decade. Most employers have baked in telehealth benefits into health plans, seen as an opportunity to bend corporate healthcare cost curves when part of value-based benefit designs. Telehealth reimbursement is also a growing practice among some managed care plans. And consumers, eager to access just-in-time care in convenient times and places (like home and workspaces), have begun to open their wallets to pay for telehealth consultations (for both physical care and mental health) out-of-pocket.

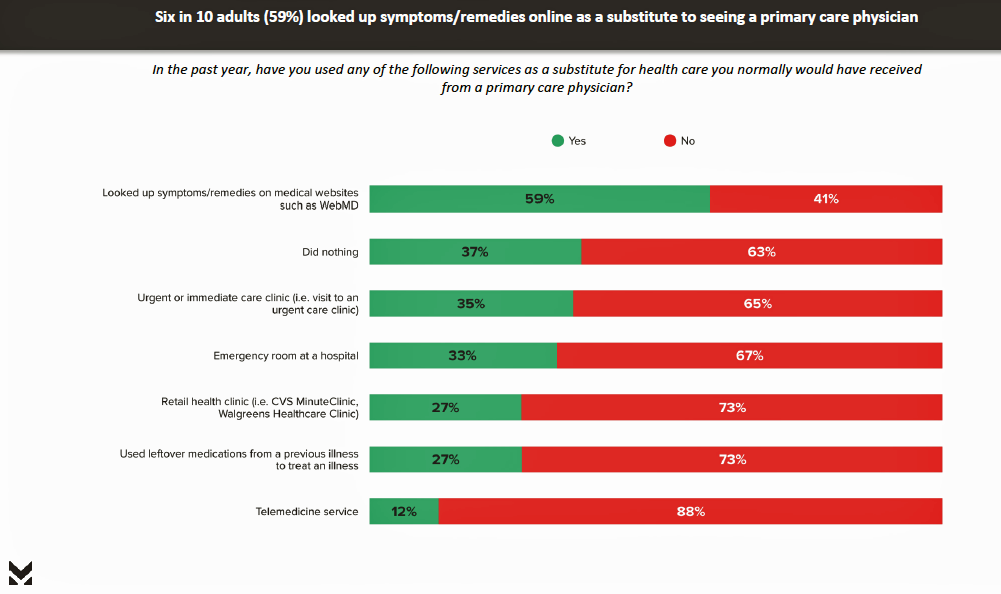

The dotHealth survey illustrates that patients, now health care consumers, are using the internet as a personal health/care platform. Other studies are confirming this, and the finding that self-diagnosis has gone mainstream. There’s additional evidence from the Morning Consult Apollo Healthcare survey released in August 2017. In the Morning Consult poll, 59% of consumers overall said they looked up symptoms and remedies on medical websites (e.g., WebMD) as a substitute for health care normally received from a primary care physician.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...