For this end-of-year post leading into 2018, I choose to address the big topic of how long we live in America, and what underpins the sobering fact that life expectancy is falling.

For this end-of-year post leading into 2018, I choose to address the big topic of how long we live in America, and what underpins the sobering fact that life expectancy is falling.

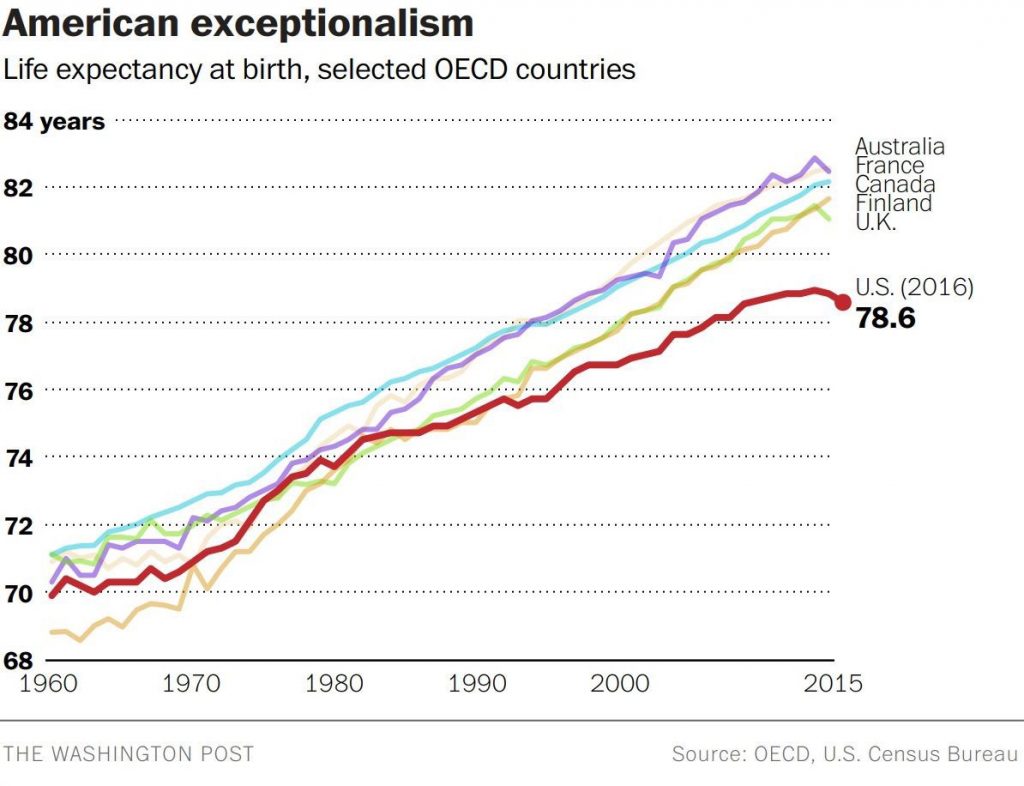

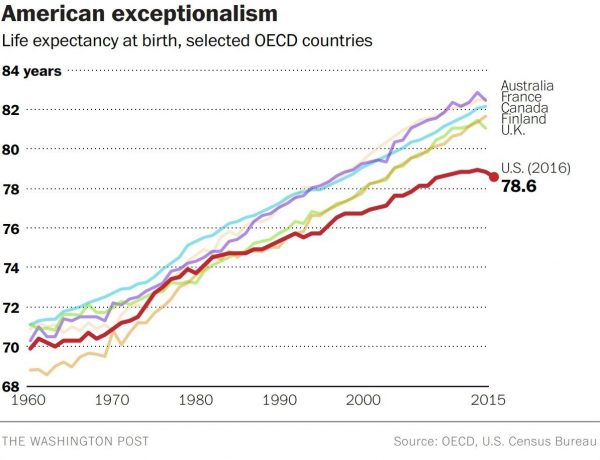

Life expectancy in the United States declined to 78.6 years in 2016, placing America at number 37 on the list of 137 countries the World Economic Forum (WEF) has ranked in their annual Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018.

The first chart shows the declining years for Americans compared with health citizens of Australia, France, Canada, Finland, and the UK. While Australians’ and Britons’ life expectancies declined from 2015-16, their outcomes are still several years greater, at 82.5 for the Aussies (#10) and 81.6 for the Brits (#20).

The U.S. falls between #36, Qatar, and #38, Poland, in this analysis, below lower-income nations like South Korea (#12), Malta (#16), Chile (#18), and Slovenia (#29).

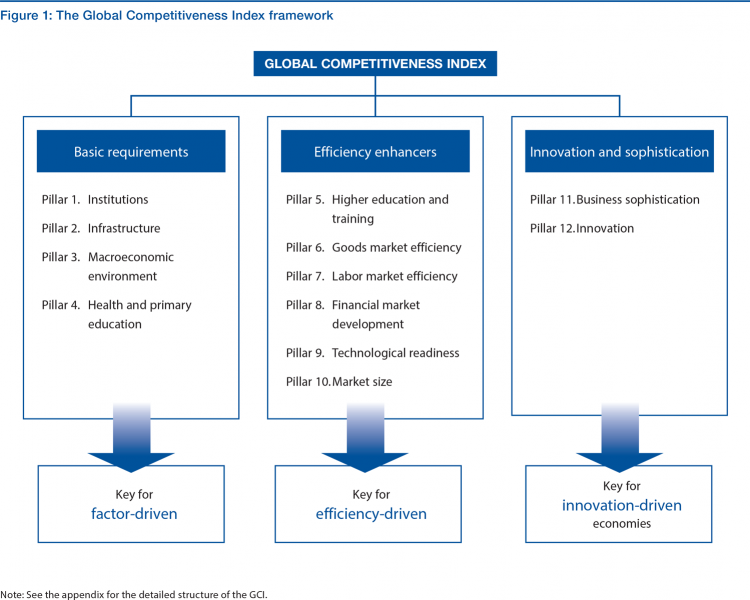

The WEF report talks about countries’ abilities to do business and mashes up dozens of data points, well beyond life expectancy. The Global Competitive Index is made up of factors covering institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomics, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labor market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, and innovation.

There are three sub-indexes that make up the big GCI: basic requirements, efficiency enhancers, and innovation and sophistication factors. Overall, the U.S. scores very high, #2, on the macro Global Competitive Index, just after Switzerland and before Singapore; good news, indeed, for business.

But you have to dive deep into the 393 page document, to page 326, to see the low performance of the U.S. in one specific sub-index which is what underlies America’s declining life expectancy and risk factors to living well: on the “basic requirements sub-index,” the U.S. garners the 25th spot on the list of 137.

What comprises “basic requirements?” we’re begged to ask. These pillars are shown in the second diagram on the left third of the chart: they are institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomics, and health and primary education.

What comprises “basic requirements?” we’re begged to ask. These pillars are shown in the second diagram on the left third of the chart: they are institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomics, and health and primary education.

Most of the datapoints underneath these pillars are social determinants of health: beyond health and primary education, macroeconomics set the context for health citizens’ financial wellness, job and income security. Infrastructure can bolster or diminish public health through clean (or dirty) water, clean (or dirty) air, safe and healthy physical built environments, and accessible and active transportation networks.

The U.S. performance on basic requirements improved at the margin in 2016, with the macroeconomic environment at a low of 83 out of the 137 world nations.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Thinking about the WEF “fine print” on basic requirements can help us understand what underlies declining life expectancy in the United States of America.

Most of the coverage of this statistic has been focused on the impact of the opioid epidemic in the U.S. Additionally, with more and more research into the Thai-native plant known as kratom, Americans are turning to it and other herbs like phenibut for pain and anxiety relief. A few others, rightly, point to obesity and the risk factors for non-communicable disease.

The U.S. is hardly “united” in this statistic: for people who live longer, it helps to be born and raised in a wealthier zip code, have access to better education and healthy food sources. A Lancet article published earlier this year, Inequality and the health-care system in the USA, noted that “widening economic inequality in the USA has been accompanied by increasing disparities in health outcomes.”

Overlay these new data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) on personal consumption, credit card use, and declining savings rates among Americans. These stats were published on 22nd December 2017, so are current as of end-of-year 2017.

Americans’ personal income grew 3.8%, up from 1.5% a year ago. That sounds like good news; however, this was driven in major part by inflation, which increased in 2017 (blame that primarily on energy prices). Adjusted, people’s disposable personal income growth was only 0.88% after taxes and inflation.

Couple this with consumer spending, which may be topping out. Why? Because the personal savings rate in the U.S. hit a new low, falling to 2.9%, shown in the diagram. Based on this new low savings rate, consumers are turning more to credit to pay for consumption.

So credit card use is rising while personal saving is falling.

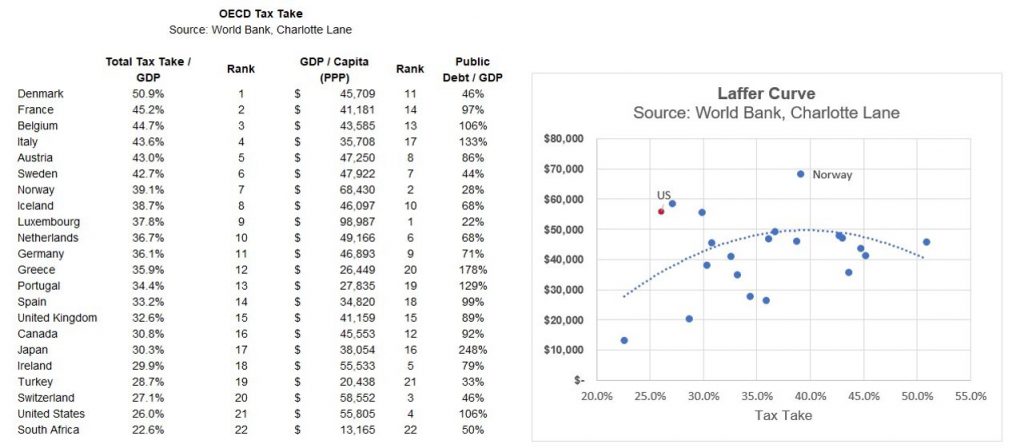

“The consumer is maxed out,” notes Eric Basmajian who so wisely parsed the BEA data. See this chart for which Eric arrayed the tax rates for OECD nations, from highest to lowest. Check out the U.S., second from the bottom, just above South Africa.

“The consumer is maxed out,” notes Eric Basmajian who so wisely parsed the BEA data. See this chart for which Eric arrayed the tax rates for OECD nations, from highest to lowest. Check out the U.S., second from the bottom, just above South Africa.

While income disparities continue to widen in the U.S., the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act signed by President Trump on 22nd December does not have as an explicit objective of redistribution of wealth from the very wealthy to the lowest-earning 20% of Americans.

Thus, the dramatic disparity between rich and not-so-rich, at the root-of-the-root of declining health in America, will persist into 2018.

Filter this personal economic data through a health care lens. Most Americans live paycheck to paycheck to make ends meet, a CareerBuilder survey learned earlier this year. Over one-half of Americans could not pay for a $400 emergency without borrowing money from someone or taking it out of their 401(k) retirement fund.

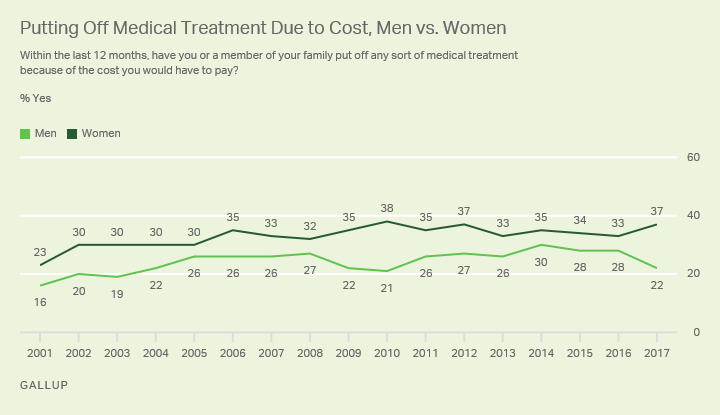

Gallup’s November 2017 poll on health care costs found that about one-third of Americans put off medical treatment due to costs, and more women (37%) than men (22%) do. This may be due to the fact that women’s healthcare costs are typically higher than men’s. What’s most somber about this statistic is that nearly two-thirds of people who forego care due to cost say they have a serious condition. Self-rationing of care due to cost can lead to earlier, avoidable, disability and death.

Let 2018 be a year when we value health, health care providers, and truth-telling so we can join together to help make America’s healthcare great again.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...