Turning 13, “we’re an unruly teenager on our hands now,” Matthew Holt invoked the start of the annual Health 2.0 Conference, convening this week in Santa Clara for its 13th year in existence.

Started with Co-Founder Indu Subaiya, Health 2.0 was conceived as a “movement,” Matthew explained. “When (we were) younger, we broke some things.” Indu continued on that riff, “we’re breaking barriers now (that) we are older, and it’s time to raise the bar.”

Started with Co-Founder Indu Subaiya, Health 2.0 was conceived as a “movement,” Matthew explained. “When (we were) younger, we broke some things.” Indu continued on that riff, “we’re breaking barriers now (that) we are older, and it’s time to raise the bar.”

In the yin-and-yang riffing style that is the brand of this duo, Matthew continued in that vein of “breaking things,” invoking a metaphor of storming the castle walls or getting through a moat, those barriers that have prevented truly transforming health care. If we can overcome these barriers, new health care services will build out a different “healthscape,” Matthew coined.

Back to Indu, who recalled, “In 2007, we had a dream.” I know that to be true, because I was there with them in spirit and on phone calls (no Skype back then), brainstorming what this conference/movement could look like.

“We wanted a health and health care system using enabling technologies in new ways…being user-centered, using data to drive decisions in an intelligent way, and developing technologies that played well with others,”

Fast forward 12 years to 2019: Indu noted that these dreams have become reality today in many ways.

Consider Mahmee, a new company breaking the mold on “where” mothers’ and childrens’ data reside. The company has designed their product on a “radical notion” that mother’s and baby’s health records should be in one place, versus the status quo scenario where OB/GYNs hold Mom’s information, and pediatricians have Baby’s new data from birth onward. This is “data driving decisions,” Indu bolstered, much as her personal Lark profile connects her 23andme genetic information, her health tracking and iPhone monitoring activity — with a chatbot asking her what she ate for lunch and suggesting, perhaps, no dessert at dinner. I know the Mahmee modus vivendi to be true in the case of my niece, a midwife employed with a major academic medical on the usual “best of hospitals” lists; this midwife was the proverbial shoemaker-with-no-shoes because after her baby was born, Mom couldn’t access the baby’s records when in the OB/GYN’s office…so much for personal data interoperability. Mahmee seeks to overcome this real-life barrier.

Consider Mahmee, a new company breaking the mold on “where” mothers’ and childrens’ data reside. The company has designed their product on a “radical notion” that mother’s and baby’s health records should be in one place, versus the status quo scenario where OB/GYNs hold Mom’s information, and pediatricians have Baby’s new data from birth onward. This is “data driving decisions,” Indu bolstered, much as her personal Lark profile connects her 23andme genetic information, her health tracking and iPhone monitoring activity — with a chatbot asking her what she ate for lunch and suggesting, perhaps, no dessert at dinner. I know the Mahmee modus vivendi to be true in the case of my niece, a midwife employed with a major academic medical on the usual “best of hospitals” lists; this midwife was the proverbial shoemaker-with-no-shoes because after her baby was born, Mom couldn’t access the baby’s records when in the OB/GYN’s office…so much for personal data interoperability. Mahmee seeks to overcome this real-life barrier.

Indu cautioned to “be careful what you wish for,” because her three dream pillars — being user-centered, data driving decisions, and playing well with others (eg., interoperable data) — can transform dreams into nightmares, as she put the situation.

Indu cautioned to “be careful what you wish for,” because her three dream pillars — being user-centered, data driving decisions, and playing well with others (eg., interoperable data) — can transform dreams into nightmares, as she put the situation.

Tech always on? Alexa recording your sex life? We must ask hard questions about the future directions of these new-new things.

Is it possible that UX-design can make things that are too personalized? Research articles in mass media like New York Times and Wired have begun to point out that our digital dust (culminating in digital phenotyping) can enable police to track us from our phones — and get it very wrong. Amazon Alexa may be holding on to our data, even when we ask her not to do so and delete audio files. So much for privacy and personal control in our own homes.

Perhaps, Indu observed, we may be playing too well together.

There’s a fundamental ambivalence, which I note in my book, HealthConsuming, in the chapter “Privacy and Health Data In-Security.” Specifically, I point to the “eoncerned embrace” of technology, observed by Deloitte in a 2016 survey of health consumers.

Health tech is not immune to this conundrum, but in health care when it comes to “your” personal care, or that for your loved ones, ‘tis better to share in the interest of caring and curing. We know from data I include in the book that people who are managing chronic or seriously acute conditions are more interested in sharing their data — for themselves in current medical management mode, and for peer patients to pay it forward for future cures.

Health tech is not immune to this conundrum, but in health care when it comes to “your” personal care, or that for your loved ones, ‘tis better to share in the interest of caring and curing. We know from data I include in the book that people who are managing chronic or seriously acute conditions are more interested in sharing their data — for themselves in current medical management mode, and for peer patients to pay it forward for future cures.

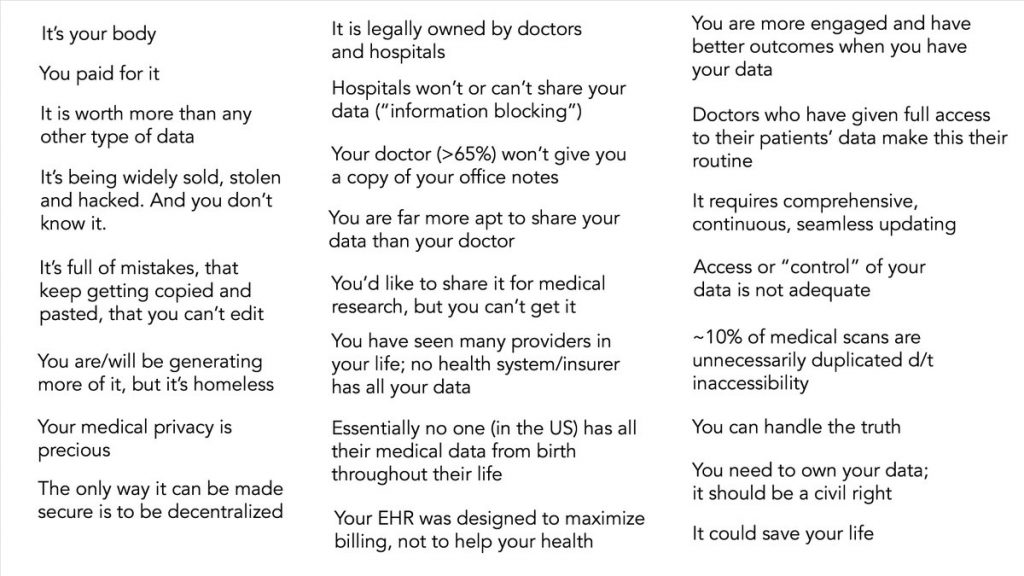

We’re going beyond ePatient Dave’s demand of “Give me my damned data (data about me).”

We’re now in an era where the vanguard of experienced patients have begun to demand data control. Indu pointed to Dr. Eric Topol’s tweet on “You.Medical.Data” which is replicated in HealthConsuming. In that vein, I just received an invitation to attend Juhan Sonin’s lecture at MIT on personal data ownership (more details here).

This concept begs the question of who’s business model is “our” data, anyway? The prospect of patients/consumers monetizing their health data is a big one, with Indu asking, “Who are you (data-driven company) making money for? New companies are forming to enable people to monetize their data, so we enter another new bioethical space in this scenario.

This concept begs the question of who’s business model is “our” data, anyway? The prospect of patients/consumers monetizing their health data is a big one, with Indu asking, “Who are you (data-driven company) making money for? New companies are forming to enable people to monetize their data, so we enter another new bioethical space in this scenario.

Indu asked what I think are the Big Question for Health 2.0 companies in this 13th year — being that curious adolescent asking the big “why” questions (you parents raising kids know of which I speak).

- “What is the relationship of your bottom line to the health of a population?”

- “Do you make more money when health improves?”

- “What is your obligation to the whole patient?”

She explained: “If I’m collecting data for somebody but my job is to treat for heart failure or diabetes, how should I partner in the (health) ecosystem so I’m not leaving (a patient’s overall) care on the table.”

Indu ended by invoking a moving essay by Dr. Donald Berwick in a recent JAMA, titled “To Isaiah.” This was the content of Dr. Berwick’s speech to medical students at Harvard. Isaiah was a patient who bravely battled and won his cancer fight. But Isaiah lost his life to a roster of social determinants of health drivers and was murdered, cut down as a young man who was “cured” by the healthcare system but let down by forces much more powerful than the toolkit in a doctor’s bag can address.

Ultimately, are we helping Isaiah?

Indu’s remarks and insights will resonate with me as I continue to promote the concept of health citizenship beyond health consumerism.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...