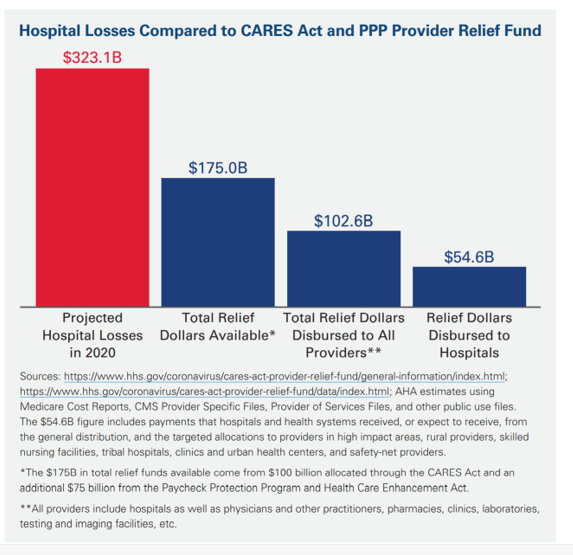

U.S. health systems are projected to lose $323 billion in 2020 due to declining inpatient and outpatient volumes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the “normal” hospital business.

Hospitals racked up over $200 bn in losses between March and June 2020. according to the American Hospital Association’s report, Hospitals and Health Systems Continue to Face Unprecedented Financial Challenges Due to COVID-19.

Hospitals racked up over $200 bn in losses between March and June 2020. according to the American Hospital Association’s report, Hospitals and Health Systems Continue to Face Unprecedented Financial Challenges Due to COVID-19.

AHA suggests that the $323 bn loss figure may be underestimated, as growing coronavirus cases are emerging in certain states: as of this writing, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah among those states heating up. Some hospitals in regions of these states are approaching full capacity in ICUs and COVID units. Thus, the AHA issued a caveat on the projection of $323 bn losses for 2020 with the proviso that, without reducing the spread of the virus and patients entering inpatient care, health system financial losses will be greater than this forecast.

What’s the worth of $323 billion? To the pharmaceutical industry, it’s the annual revenue generated from 323 blockbuster drugs, as “blockbusters” are defined as products yielding $1 bn in sales a year.

“Hospitals and health systems are committed to ensuring the safety of their patients and sataff, as wella simproving the health of our country,” this report explains. “It’s likely that these policies wille xtend financial recovery for hospitals and health systems, because of their effects on patient flow and hospital volumes.”

By early June when AHA surveyed 1,360 hospitals across 48 states, average reductions across the country were 19.5% declines in expected inpatient volume and 34.5% fall in outpatient volume.

There are two sides to this decline in volumes: the consumer/demand side, and the health system/supply side.

On the consumer-demand side, one in two U.S. adults surveyed in the May 2020 Kaiser Family Foundation Tracking Poll had skipped or postponed medical care in the past three months due to concerns about the coronavirus. One in four people said they would wait at least four months to get back to the doctor’s office.

On the consumer-demand side, one in two U.S. adults surveyed in the May 2020 Kaiser Family Foundation Tracking Poll had skipped or postponed medical care in the past three months due to concerns about the coronavirus. One in four people said they would wait at least four months to get back to the doctor’s office.

On the supply side, in the interest of bolstering public health and that of staff, hospitals and health systems have put in place many policies and restrictions, AHA notes: limiting bed capacity, reserving PPE (which can lead to cancelling/postponing procedures and surgeries), and screening staff and new patients for COVID-19, among other tactics that have reduced access or volume flowing to and through the hospital.

Two in three hospitals polled said they did not expect to achieve their expected baseline volumes by the end of 2020.

Hospitals noted additional costs they expected could exacerbate their financial situations. These included:

- Drug acquisition and drug shortage costs

- Wage and labor costs

- Uncompensated care costs (owing to the sharp upturn in unemployment in the U.S., leading to growing un- and under-insured people)

- Non-PPE medical supplies and equipment costs, and,

- Capital costs for filling the need for additional treatment capacity when needed.

Even with funding flowing to hospitals from the CARES Act and the PPP Provider Relief fund, there will remain a gap of

Kaufman Hall’s June 2020 National Hospital Flash Report noted that median hospital operating margin rose 4% in May, versus what it would have been without the government support: -8.0%.

That’s a snapshot, immediate-term blip, because CARES funding was allocated in April and May, with no plans yet from Congress to add to the relief pot.

“If the current surge trends continue,” AHA warns, “the financial impact on hospitals and health systems could be even more significant.”

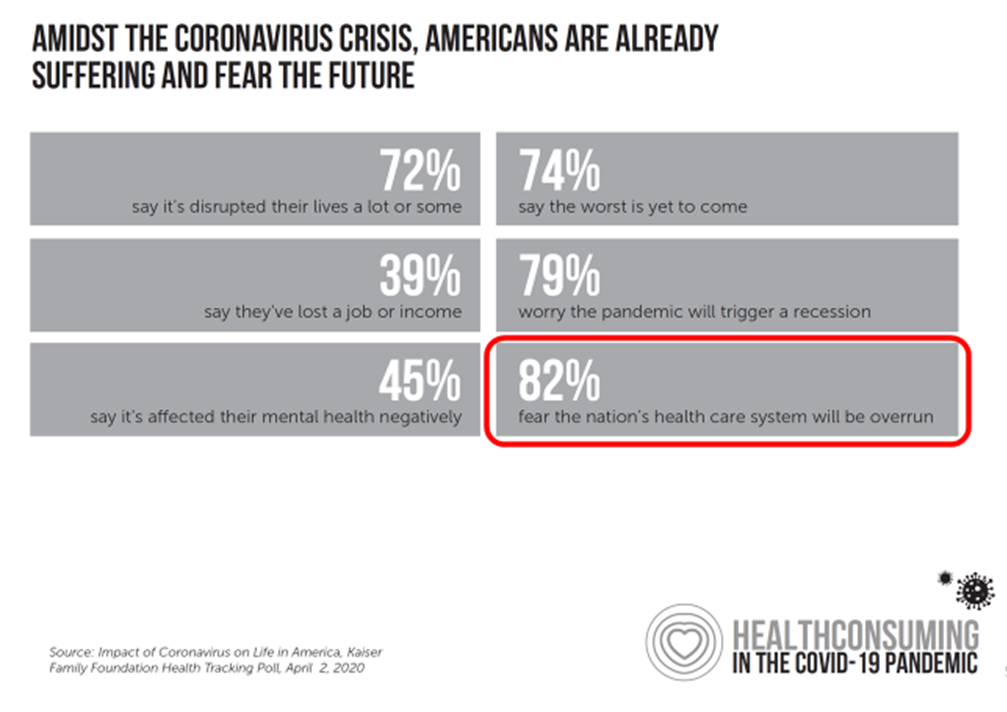

Health Populi’s Hot Points: By April 2020, a month into the pandemic, most Americans feared the health care system would be overrun by the virus’s impact.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: By April 2020, a month into the pandemic, most Americans feared the health care system would be overrun by the virus’s impact.

Many media stories have portrayed mask-less Americans congregating on beaches and in bars up-close-and-personal in fear-of-missing-out mode (FOMO). But there’s a large percentage of people with “FOLH:” fear-of-leaving-home, as I’ve coined it in the Age of Corona. Millions of people — including lots of patients managing chronic conditions and cancer — have postponed returning to health care visits and to other parts of life outside, from retail to barbershops and auto malls.

The rise of telehealth in the pandemic has been a positive artifact, insofar as virtual care has expanded patients’ access to consulting with clinicians and avoid exposure to the virus in doctors’ offices or hospital ambulatory clinics.

At the same time, virtual care has enabled clinicians to risk-manage exposure to COVID-19 for themselves and their staff.

Millions of patients-as-health-consumers experienced telehealth for the first time in the pandemic, most of whom expect to have the option of virtual care platforms after the crisis subsides.

In today’s Cain Brothers’ Comments (dated July 1, 2020), Matthew Margulies and David Johnson assert that, Home Health Is Where the Growth Is, explaining the post-COVID rise of platform solutions.

The top-line is that, even before the pandemic, home health care was “on the march,” the Cain Brothers team writes, as financial pressures intensified and value-based payment models advanced among providers and payers.

As hospitals suspended non-essential procedures and reduced the volumes, as AHA quantified in their report, demand for care at home grew. While home health has typically focused on post-acute nursing, therapy, hospice and personal care, payment models have expanded the concept of home as one’s health hub, to address social determinants of health: food, transportation, loneliness and social connection, among other touch points of social care.

Hospitals must continue to pivot operations in the necessary “now,” as COVID-19 hasn’t yet been extinguished and, in some parts of the U.S., is accelerating in infection rate and inpatient admissions.

At the same time, hospitals must re-imagine care outside of the hospital walls, as they deal with declining margins in 2020. The person’s home will evolve into a place of healthcare that’s safe, accessible, and satisfying, even empowering. Hospital financial managers must sort out how to make the math work, as we begin to see examples of hospital-at-home programs emerging among forward thinking institutions.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...