“Digital,” write large, has been a lifeline during lockdown for those with the access, skills, and confidence to benefit from connecting.

“But too many [people] are still locked out,” the Good Things Foundation explains in Digital Inclusion in Health and Care: Lessons learned from the NHS Widening Digital Participation Programme.

This report details how the National Health Service in the UK — the largest health care delivery system and single payor in the world — developed a model of “digital health hubs” to help address widening health inequities made worse through digital divides in the United Kingdom.

This report details how the National Health Service in the UK — the largest health care delivery system and single payor in the world — developed a model of “digital health hubs” to help address widening health inequities made worse through digital divides in the United Kingdom.

There are many lessons the U.S. can learn from the Widening Digital Participation program’s work over 2017 into 2020. These learnings are especially, crucially important in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. which has revealed America’s digital divide that has worsened health, social, and economic impacts for people lacking digital inclusion addressing connectivity, literacy, and trust.

The Good Things Foundation collaborated with NHS England, NHS Digital, and NHSX in a partnership called Widening Digital Participation, starting in a first phase of work in 2013 which focused on improving digital literacy in communities.

The Good Things Foundation collaborated with NHS England, NHS Digital, and NHSX in a partnership called Widening Digital Participation, starting in a first phase of work in 2013 which focused on improving digital literacy in communities.

FYI, NHSX is a joint program that includes teams from both NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care, convened to drive digital transformation in care for people in Britain.

The second phase of the project ran from 2017 to 2020, bringing together community stakeholders and patients to co-design health and social care solutions underpinned by digital tech.

The project ended in March 2020 as the UK entered lockdown in the early phase of the pandemic. In March 2020, online health care consults in the UK doubled to 1.8 million from 900,000. This report was written with additional context of and wisdom gained through the coronavirus public health crisis.

The bottom-line results were financially impactful: Widening Digital Participation yielded a return-on-investment of £6 for every £1 spent on the program.

The program yielded eight major lessons and action areas:

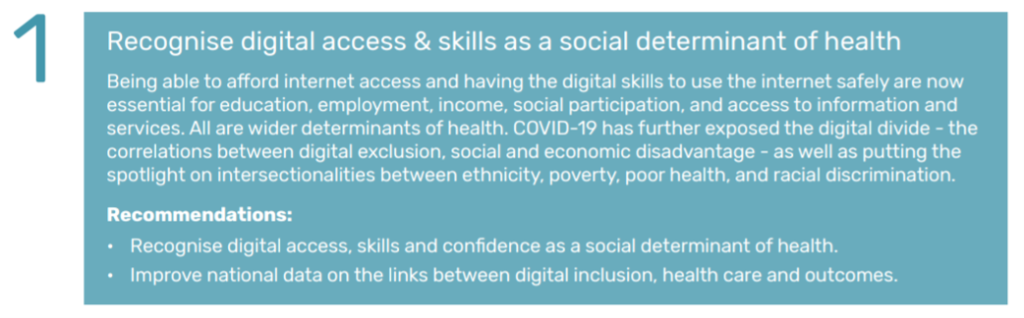

- Digital access and skills are a social determinant of health

- Employing co-design as a method of involving patients, the public, providers and decision makers bolsters the success of ideation, program development, and implementation

- Improving digital health literacy in the community is key for reducing health inequalities

- Developing “digital health hubs” improves inclusion and helps to reduce health inequities

- Building trust and relationships with poorly-served groups of people mitigates barriers to people access digital health services — especially when supported by “people like me” who speak “in my language”

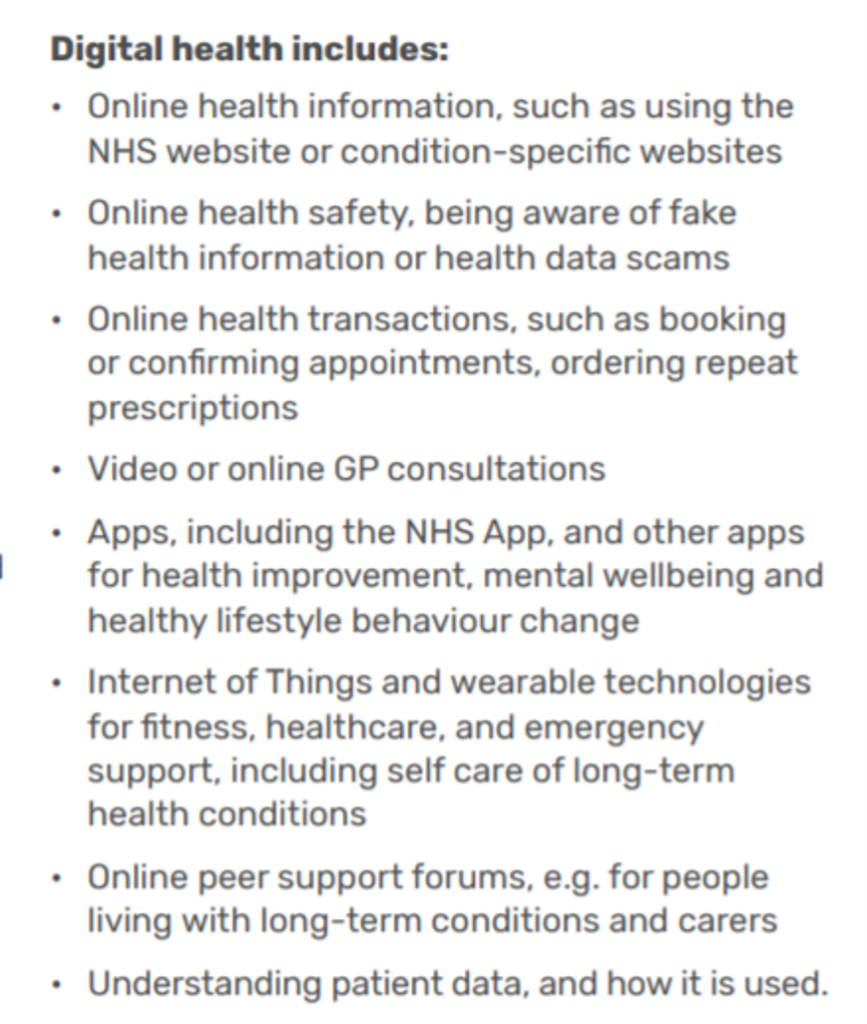

- Harness the benefits of digital for health and well-being, addressing accessibility and assistive technologies

- Improve digital skills in the health and care workforces

- Embed digital inclusion in health, care and well-being strategies.

The project also identified enablers and barriers to succeeding in digital inclusion that drives healthy outcomes. Key enablers spoke to atmosphere and approach (a friendly and welcoming atmosphere bolstered success); using digital devices and connectivity that people already used and with which they felt comfort and trust; deploying staff and volunteers who are ready to explore digital health together; “going where people are,” tapping their interests in local communities; and engaging local health care providers who are part of their community fabric.

The project also identified enablers and barriers to succeeding in digital inclusion that drives healthy outcomes. Key enablers spoke to atmosphere and approach (a friendly and welcoming atmosphere bolstered success); using digital devices and connectivity that people already used and with which they felt comfort and trust; deploying staff and volunteers who are ready to explore digital health together; “going where people are,” tapping their interests in local communities; and engaging local health care providers who are part of their community fabric.

Key barriers included limited local provider engagement; diversity and fragmentation of existing online services and systems (in the U.S., think: interoperability as part of this barrier); time and resource limitations; and, depth and diversity of local community needs.

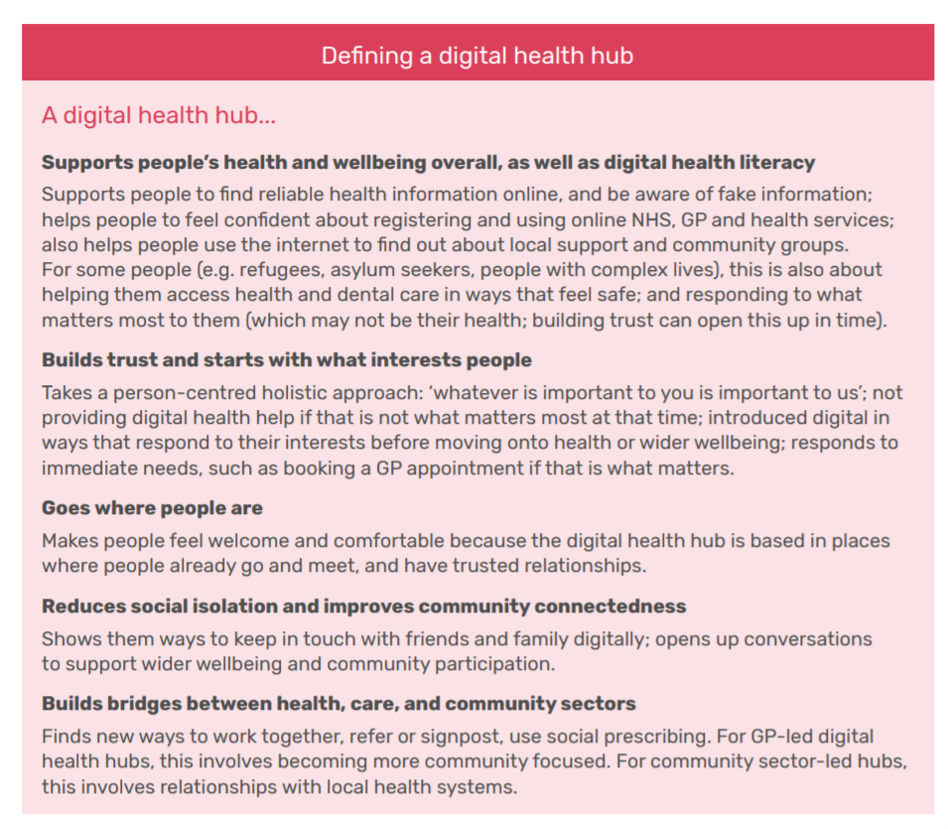

Based on these learnings, the project developed the concept of digital health hubs, defined in some detail in the pink box.

A digital health hub is physically embedded in a local community, responsive to local peoples’ values, staffed by paid workers, volunteers, and peers, build through local partnerships and assets, and focused on supporting local peoples’ health and well-being.

The vision here is to connect the community-based digital health hubs into a national networked community of practice, to share learning and bolster health and digital literacy for all the nation’s health citizens.

The vision here is to connect the community-based digital health hubs into a national networked community of practice, to share learning and bolster health and digital literacy for all the nation’s health citizens.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The Good Things Foundation’s vision is a world where everyone benefits from digital: “We tackle the most pressing social issues of our time, working with partners in thousands of communities across the UK and further afield,” their statement of purpose asserts.

Part of the Foundation’s ethos is their embrace of co-design principles. There are six of them:

- Design with people, not for them. People are the experts in their own lives.

- Go where the people are. Spend time where folks live, work, pray, learn, shop.

- Realize that relationships are not transactions.

- Work in the open: share learning, share work, be transparent.

- Under underlying behavior. Look beyond the immediate surface to understand the many factors driving peoples’ decisions. Check the assumptions you make.

- Do it now.

“Get it out there. See what works and doesn’t,” the Foundation urges us onward.

The coronavirus pandemic has awakened weaknesses in health and social care the world over, those systemic warts expressed in different ways in different countries based on each nation’s organization and financing of health care, social services, infrastructure, financial, and indeed, digital inclusion.

In the U.S., digital inclusion during the pandemic has been a factor in peoples’ ability to live, work, attend school, pray in groups, and socialize, among other daily life-flows.

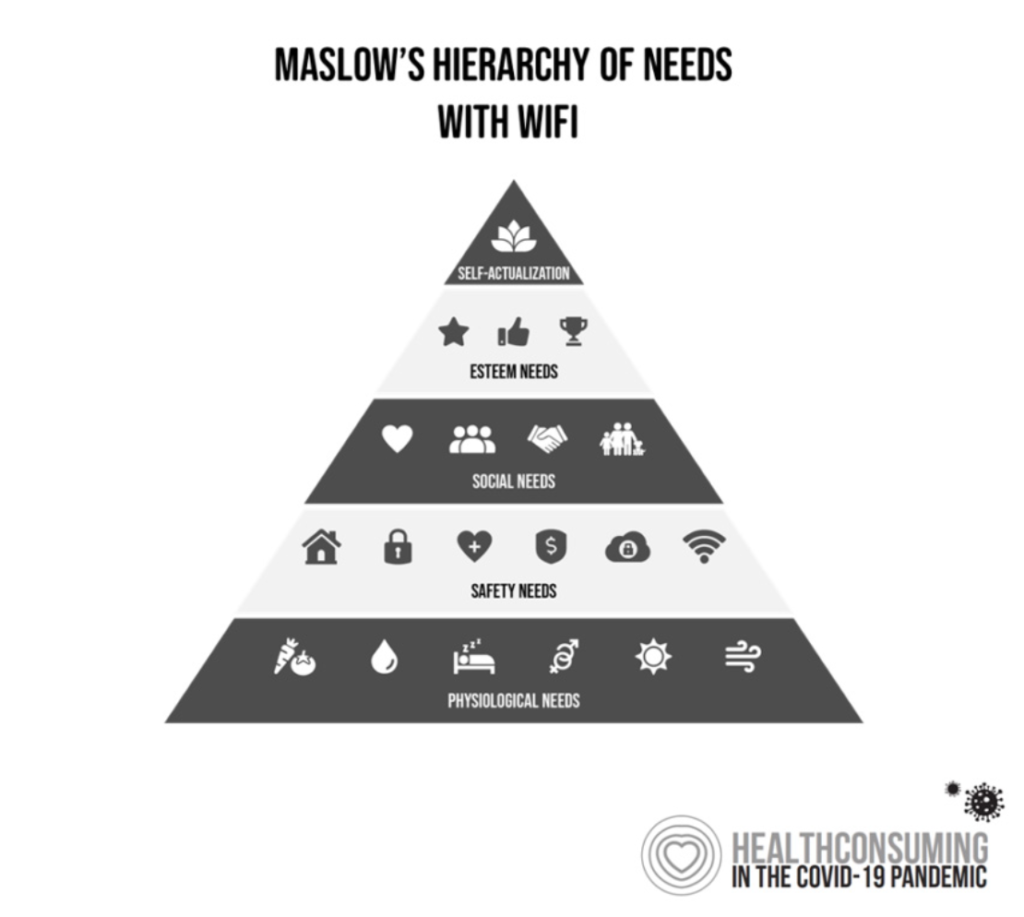

The last diagram, of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, includes WiFi as a basic need on the “safety” run of the pyramid.

The last diagram, of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, includes WiFi as a basic need on the “safety” run of the pyramid.

In fact, “digital” was necessary in the pandemic era in America to live, or at least try to live, a semi-normal life style in the era of mandated staying home from work, school, and social lives.

The NHS and Good Things Foundation came to understand the profound implications and benefits of digital inclusion for health citizens of the UK. Key among these was designing with, and not for, people.

There are many reasons in the U.S. that prevent people from being “digitally included.” Barriers to that include the lack of broadband infrastructure in communities (in and beyond rural ones); lack of access to digital platforms for connecting (such as smartphones, tablets, and computers); lack of finances to pay for connectivity, for either or both the phone or the data plan connecting the hardware to the Internet; lack of knowledge about the importance and value of connecting; lack of well-designed digital apps and tools that “speak” to people who use a language other than English, or communicate in culturally-relevant terms.

I highly recommend your exploring the NHS/Good Things Foundation report if you are working to better health care in America. The challenge of digital inclusion will persist long after the coronavirus pandemic is extinguished within U.S. borders, underpinning a larger issue of equity, well-being, and economic development in America.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...