In the U.S. in 2021, per person health care spending increased by nearly 15%, reversing 2020’s spending decline of 3.5% in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The latest Health Care Cost and Utilization Report from the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) details health spending in 2021, dissecting the change in terms of utilization of services and prices by category.

That’s a big rise over consumers’ household inflation for food, energy, and other kitchen-table considerations, prompting me to look for additional context from a recent paper published by the OECD on Health care financing in times of high inflation,

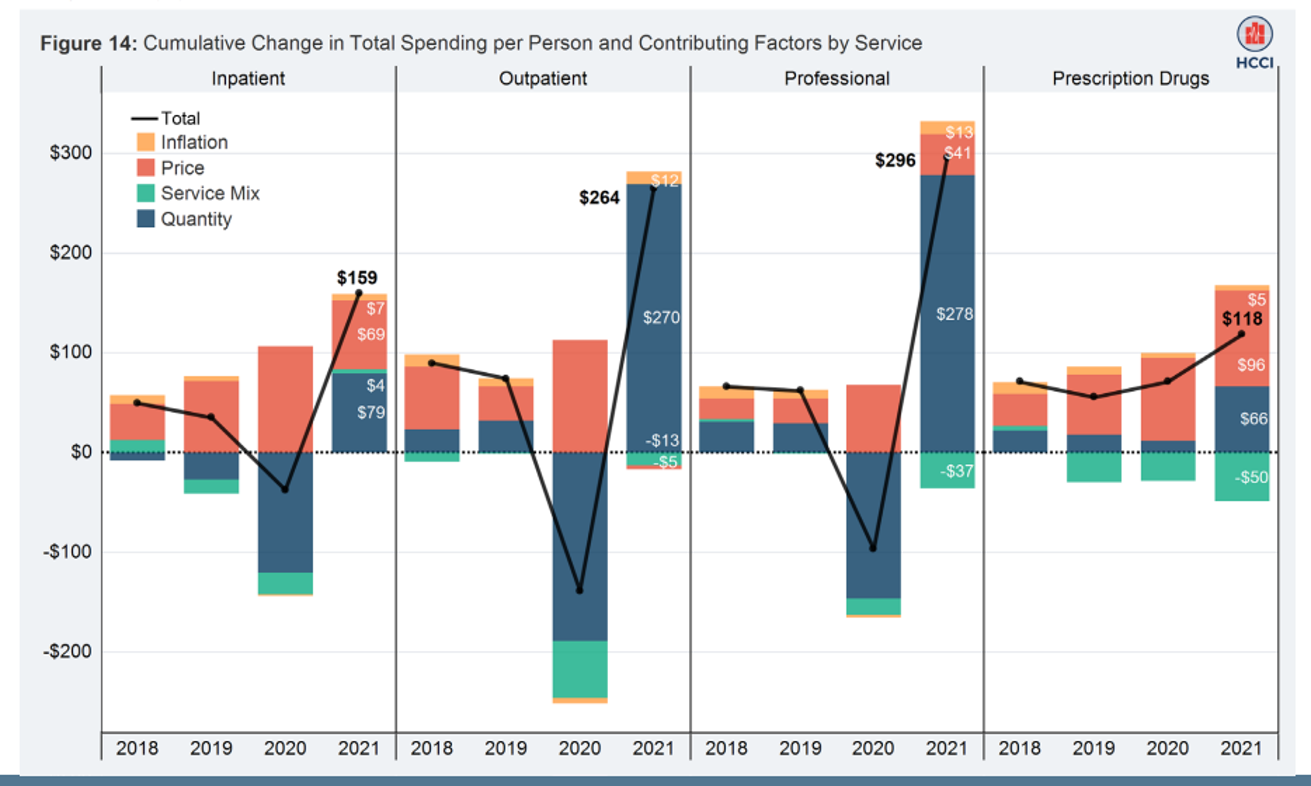

The first chart illustrates the cumulative and annual spending changes between 2017 and 2021′ spending is the combination of utilization (volume) times price of services. The dip in patient volumes is easy to see in 2019-20, followed by the hockey stick increase in 2020-21 for utilization, signally some patients’ return to health care services.

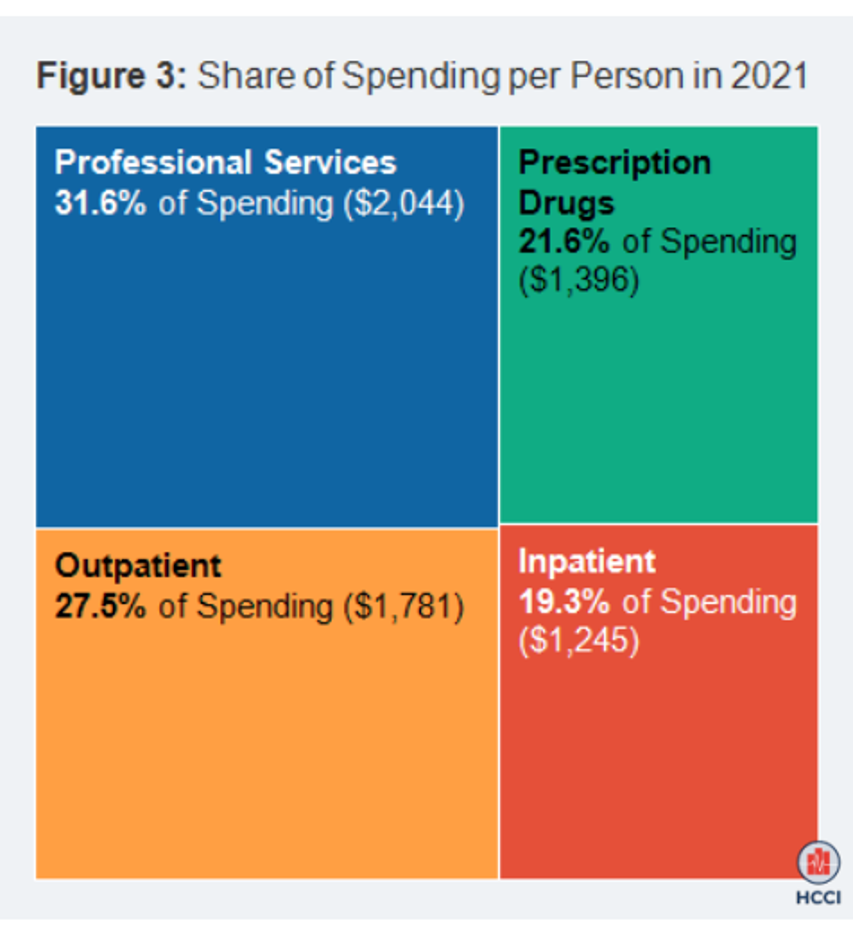

By 2021, the largest share of spending per U.S. health citizen was for professional services, comprising nearly $1 in $3 of health care spend. Outpatient spending comprised just over $1 in $4 per capita, followed by prescription drugs which were allocated over $1 of every $5. Inpatient costs fell just below the prescription drug share of spending per person in the U.S.

Total spending, cumulatively, increased by 21.2% between 2017 and 2021. But there is an important inflationary/increasing difference in spending for prescription drugs compared to the other three categories: prescription drugs grew the most cumulatively in the period 2017 to 2021, by 29%, followed by inpatient, outpatient, and professional services which each increased roughly 19-20%.

For prices, it was inpatient costs that rose most cumulatively between 2017 and 2021, by 28%, versus 17% for prescription drugs, 9% for outpatient and 7% for professional services.

The last bar chart breaks these differences out by service in terms of the cumulative change in total spending per capita.

You can clearly see the utilization (quantity) of outpatient, professional and inpatient services drop in 2020, with rebounding in 2021 for all four categories of health care spending.

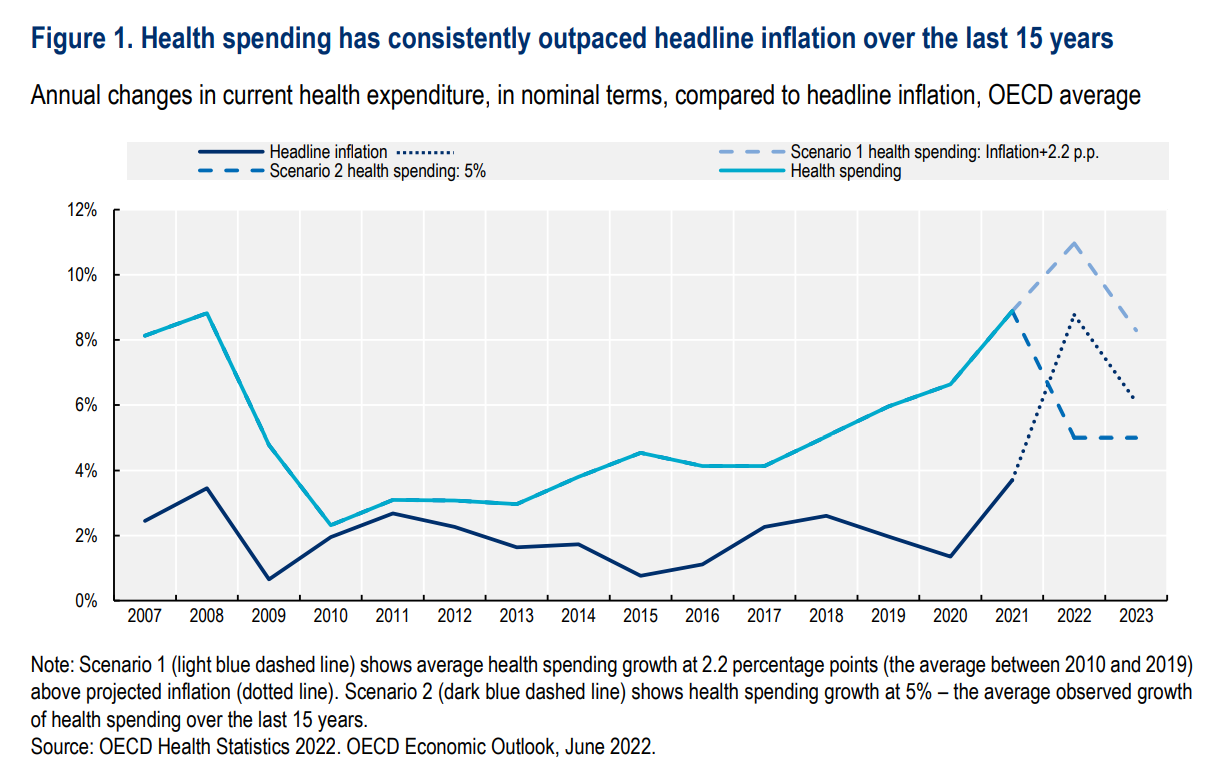

The OECD report summarizes health spending for the most developed/wealthy countries in the world, finding that health spending has consistently outpaced inflation for 15 years. That’s represented by the lighter blue line in the first chart.

“Spending on health jumped by almost 1% of GDP across OECD countries,” the report noted, “as governments stepped in to cover unexpected public health and treatment costs.|

“The crisis highlighted the need for further investments to strengthen health system resilience in the face of new shocks,” the OECD asserts

The Russia war in Ukraine, continued supply chain challenges for some essential goods, and inflation stressing mainstream consumers in many countries are forcing many health citizens to trade-off household spending between “heating, eating, and being well,” Richard Edelman recently noted explaining the health/care implications embedded in the 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer.

In light of inflation and increasing health care costs among the OECD nations, of which the U.S. is one, “policy options remain limited” the Organization calls out, warning that the health care cost “spending spree” must now be tempered with greater efficiencies and wringing out wasteful spending.

In addition to making cutting out waste in healthcare spending Job 1, OECD also notes that medical errors also represent waste in clinical settings, and that employing trained clinical workers to function at the top of their abilities could also be a useful strategy for cost-saving and extending care for access.

OECD finally recognizes that all stakeholders in the health/care ecosystem have roles to play in being more efficient, effective, and engaging in getting more value out of health care spending. That sandbox includes health care providers and hospitals, physicians and ambulatory care sites, pharma and medical device companies, and indeed — patients, as well, who can improve in healthier lifestyles, self-care, and addressing risk factors under personal control when possible.

Watch for each of the stakeholder groups’ messaging to point fingers in the ongoing health care cost blame game: here is the recently published link to AHIP’s analysis of prescription drug pricing, the AHA’s report via Kaufman Hall on the need for financial reserves (speaking to hospitals’ fiscal health in light of challenging reimbursement), and Primerica’s survey of U.S. middle-class households finding that health care has returned to the #1 household fiscal concern ahead of inflation in 2023. All health ecosystem players are organizing for 2024’s national elections.

The OECD report also hinted at the possibility of increasing taxation on the private sector (which could be either or both taxpaying consumers or companies/business) to supplement funding for the public sector. This is, to be sure, going to be a discussion/debate point in the U.S. approaching the 2024 November elections for Congressional platforms along with what the next President elected talks of doing to re-build a more resilient U.S. healthcare system that can weather the next pandemic and exogenous shock to the American economy — both the macroeconomy and the health economy itself.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...