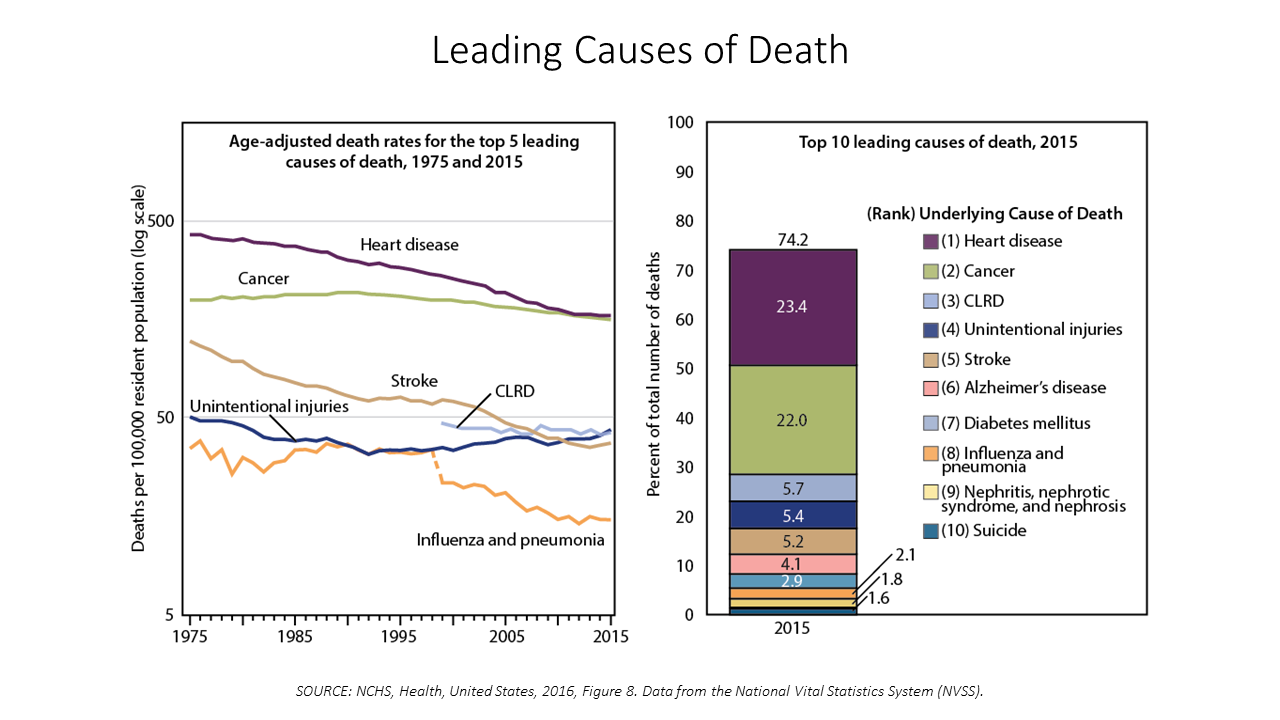

Between 2014 and 2015, death rates increased for eight of the ten leading causes; only death rates caused by cancer fell, and mortality rates for influenza and pneumonia stayed flat.

Between 2014 and 2015, death rates increased for eight of the ten leading causes; only death rates caused by cancer fell, and mortality rates for influenza and pneumonia stayed flat.

The first chart paints this sobering portrait of Americans’ health outcomes, presented in the CDC’s data-rich 488-page primer, Health, United States, 2016.

Think of this publication as America’s annual report on health. Every year, it is prepared and submitted to the President and Congress by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services. This year’s report was delivered by DHHS Secretary Tom Price to President Trump and the 115th Congress.

The report covers Americans’ health status and determinants of health, health care resources (such as hospitals, doctors, long-term care, and other inputs), use of those resources, and health care spending.

This latest version is the 40th edition of Health, United States, and thus provides an opportunity to understand long-term trends in U.S. health care, patient outcomes, and spending.

Key findings from this report include:

In health outcomes…Between 1975 and 2015, life expectancy at birth in the U.S. increased from 72.6 to 78.8 years for all Americans. Life expectancy was 76.3 years for men and 81.2 years for women.

There was improvement in life expectancy at birth for black Americans versus whites, narrowing the disparity between the two groups: in 1975, life expectancy for whites was 6.6 years longer than for black Americans, falling to a 3.5 year difference.

While the infant mortality rate fell 63% from 16 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1975 to just under 6 deaths per 1,000 in 2014, the rate for non-Hispanic black mothers was much higher at nearly 11 infant deaths per 1,000 live births.

In utilization of health resources…The percentage of U.S. health citizens going for health care visits rose between 1997 and 2015 (a proxy for access moving in a positive direction).

The percentage of patients under 75 years staying overnight in hospitals declined, and was stable for those 75 and over.

The rate of prescription drug use grew to 2014: in the past month, with By age, 36.5% of adults 18-34 taking at least one Rx drug in the past 30 days; 70% of people 45-64 taking a prescription in the past month; and 91% of folks aged 65 and over taking at least one Rx in the past 30 days.

An important micro-trend within the Rx prescription rate points to significant growth among older people 65 years and over using five or more prescription drugs in the past 30 days: rising 28.4 percentage points for this age group between 1994 and 2014. The report notes that Rx use over the past 40 years has been driven by many factors, including medical need, new drug development and approval, growth in direct-to-consumer (DTC) promotion, and expanding prescription drug coverage in insurance markets. The use of five or more drugs, aka polypharmacy, is a concern that can increase the risk of drug-drug interactions, adverse drug events, and reduced functional capacity, the report adds.

For utilization of health services…Visits to emergency departments fell in 2015 from the previous year for all patients but those without health insurance.

For utilization of health services…Visits to emergency departments fell in 2015 from the previous year for all patients but those without health insurance.

Use of mammograms and colorectal cancer tests increased for all racial and ethnic groups, but disparities still persist among people of color.

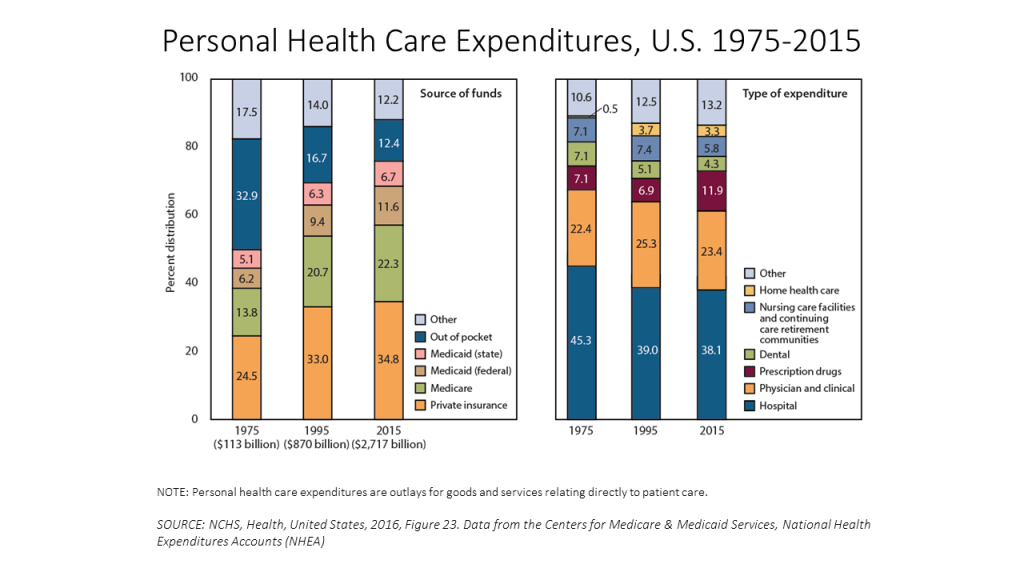

Health care spending in the U.S. grew to comprise nearly 18% of the GDP in 2015, from 7.9% in 1975. Money going to hospitals fell as a percent of total spending, as costs for Rx drugs grew from 7% to nearly 12% in 2015. Spending on physicians and clinical services was flat, around 23%, over the period.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Nearly one-fifth of the U.S. economy is allocated to healthcare, but use of resources and outcomes achieved are not spread equally across U.S. health citizens. The issue of health equity should be a central discussion during the current health reform debate as Congress wrestles with re-inventing the Affordable Care Act to either repeal it, replace it, or refine it.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Nearly one-fifth of the U.S. economy is allocated to healthcare, but use of resources and outcomes achieved are not spread equally across U.S. health citizens. The issue of health equity should be a central discussion during the current health reform debate as Congress wrestles with re-inventing the Affordable Care Act to either repeal it, replace it, or refine it.

“Pursuing Health Equity” is the timely theme of the June 2017 issue of Health Affairs. “Growing understanding of social factors in determining health outcomes makes it clear that achieving equity requires widening the lens,” Editor-in-Chief Alan Weil writes in his introduction to the topic, highlighting the research articles’ broad coverage on the challenge of health disparities.

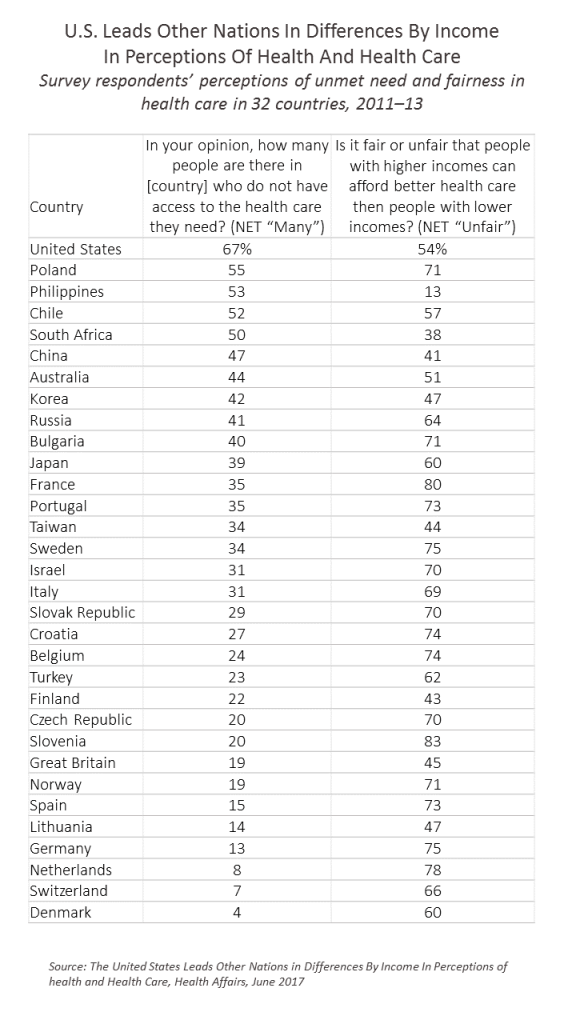

In Health Affairs, research based on data from a survey done in 2011-2013 analyzed by Joachim Hero, Alan Zaslavsky, and Bob Blendon, points to a “sobering” finding (in the words of Weil): compared with people living in 32 developed countries, the U.S. was an outlier in the number of people who didn’t believe it was “unfair” that those with higher incomes could afford better health care than people with lower incomes.

In other words, in 2013, health inequity in the U.S. was acceptable to 46% of Americans.

Today, this may be reflected in Americans’ apparent divide in health reform politics, where about one-half of health citizens are more likely to support major health system reforms and the other half, not-so-much.

“As the United States contemplates the future of its health care system, the results of this study are a stark reminder of how far the country had lagged behind its peers in correcting health and health care disparities before the reforms of the ACA,” the authors write.

The ACA bolstered efforts to deal with health disparities through covering preventive care, prescribing a minimum benefit package, and bolstering the country’s primary care backbone to provide a more resilient on-ramp to community-based health care services.

Getting to health equity in the U.S. would lower costs for more intrusive, intensive, technology-based care. Providing health insurance security to all is a necessary but not sufficient path to achieving health equity in America. Spending more on social care to ensure good education, healthy food systems, transportation to take people to where jobs are, and assuring financial wellness are all investments healthy countries make to advance a health citizenry. Interestingly, the very countries whose majority of health citizens said it’s “unfair” that people with higher incomes can afford better health care are those countries that have stronger primary care backbones and social care infrastructure.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.