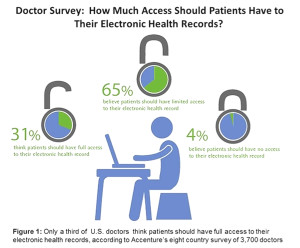

Only one-third of U.S. physicians believe that patients should have “full access” to their electronic health records, according to Patient Access to Electronic Health Records What Does the Doctor Order?, a survey conducted by Accenture, released at HIMSS13 in March 2013. Two-thirds of doctors in the U.S. are open to patients having “limited access” to their EHRs. However, the extent to which doctors believe in full EHR access for patients depends on the type of health information contained in the record.

Accenture surveyed 3,700 physicians in eight countries: Australia, Canada, England, France, Germany, Singapore, Spain and the United States, and found the doctors’ responses to be roughly similar across the globe.

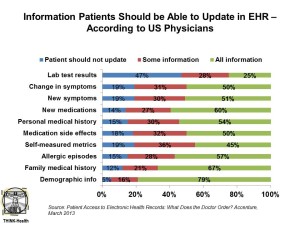

The data shown in the bar chart are for U.S. only so we can be specific about American physicians’ views on just how much they want to open their collective EHR kimono to updating by patients.

The most sacrosanct kind of health data in the EHR which patients should not be able to update is lab test results, an opinion held by about one-half of U.S. physicians. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the areas where U.S. physicians believe physicians could update “all information,” are demographic information (79% of physicians), family medical history (67% of physicians), and allergic episodes (57% of physicians).

A growing aspect of self-care among health consumers is self-tracking via digital devices, a category of consumer electronics that is fast-becoming mainstream through the use of digital activity trackers and blood pressure monitoring at home, for example. However, only 45% of doctors in the U.S. believe that patients should be able to fully update their EHR with this data.

I met with Kaveh Safavi, Managing Director of Accenture’s Health Industry practice, at HIMSS to discuss the survey. “We’re netting this out that physicians are not as reticent about patient participation in putting information into the record than we might think. There’s a large group generally comfortable provided certain protections are in place,” Kaveh said. “This will create a potential use case for the EMR to be more than just a ‘medical record,’ but a platform for shared decision making, Kaveh believes.

It’s the “second layer” that’s of concern, Kaveh perceives. “Its’s the doctors’ notes they have anxiety about and they don’t want patients to over-write information” that’s in the EHR. “If I make a decision today,” Kaveh explained, “and a patient writes on it tomorrow,” the physician wants to make sure they don’t lose their original notes. To manage this going forward, Kaveh suggested that health care look to other industries for examples where digital records change over time: for example, in banking and financial services. “You can’t change a bank balance,” Kaveh noted, but the system notes when a consumer deposits or withdraws money from an account, dated and verified by the system.

Ultimately, Kaveh concluded, “We are encouraging our customers (that is, health providers) to think clearly about getting patients involved. This is part of the economics of lowering costs of providing services. Every industry has figured out that shifting work to customers lowers the cost of production and leads consumers (read: patients) to feel part of the process.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The results of the survey beg the question: do physicians welcome patients in a shared decision making, participatory health role in parity with them?

Based on the data, the answer is mixed, depending on your lens on the data. Doctors feel comfortable with patients updating EHRs for only certain kinds of information — say, for the most obvious data points like demographic information (79%) and family medical history (67%). But even here, where patients clearly know more than their doctors about their ethnicity, family income, and job status, as well as parents’, aunts’ and siblings’ health experiences, clinicians don’t universally welcome patients to correct even that personally-held information.

When it comes to more clinical issues, such as medication side-effects, only 50% of doctors would welcome patients’ entry. Yet this issue is quite a personal one, where the patient — and only the patient — can articulate how they feel on the drug. For example, how is their sex life affected by a prescription drug? Do they feel depressed taking the medication? Thoughts of suicide? Some patients might feel easier entering their perceptions of drugs’ side-effects online versus face-to-face with a doctor. Similarly, with only 54% of physicians saying that patients should be able to update personal medical histories, the EHRs may be missing some important private stories that patients want to play close-to-the-vest: living on the down-low, perhaps, or a past history of abusing prescription drugs or treating a sexually transmitted disease.

“The EMR may not be a respository but more a platform for some level of engagement,” Kaveh Safavi told me at HIMSS. “Patients putting information into the EHR is likely to have some positive impacts on accuracy…and also a level of engagement. When people participate in building something, they have a sense of ownership in that.”

The Accenture survey serves as an important counterpoint to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Open Notes project. In Open Notes, RWJF asked patients their side of the question: “What would happen if you could peek inside the chart and see what your doctor has been recording about you?” Over 100 primary care doctors and 25,000 patients in Boston, rural Pennsylvania and Seattle. The three key learnings from the study were that:

- Patients expected to benefit from better communication with their doctors, better retention of the information they heard during the physician visit, and enhanced ability to build a “personal care network” with family and friends. Patients’ concerns included their inability to understanding medical language, protection of their privacy, and changing the nature of their relationship (for the worse) with their personal physician.

- Doctors were concerned about threat to their workflow and loss of time if patients “engaged rigorously” with their medical records, as well as worrying about making the language in the EHR less precise due to having the “translate” medical terminology into layman’s language.

- On the upside, physicians saw benefits to Open Notes, such as more accuracy in the records, improved patient understanding of what they learned in the visit, and better relationships with patients and their families.

The Open Notes project explicitly calls out that under HIPAA, all patients in the U.S. have rights to their full medical records — including doctors’ notes. However, the process in getting those records and notes can be “slow, cumbersome and even expensive.”

The patient advocate Regina Holliday is the most visible and activated example of someone who tried to access medical records on her (very ill) husband’s behalf, and hit a brick wall in doing so. Once you hear her and husband Fred’s story, 73 cents, you may come to appreciate how many miles we still have to go to get to real shared decision making in health care.

The Accenture survey points out that physicians still hold patient data as proprietary. This is an obstacle to shared decision making between patients and doctors, and will prevent full-on health engagement that can drive optimal health outcomes for patients, improved health literacy, and a stronger health economy. Regina’s work, and the work of those demanding participatory health rights guaranteed under HIPAA and bolstered by common sense and health economics, will continue. For more on the goals of participatory medicine for both patients and doctors, visit the website for the Society for Participatory Medicine.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...