On July 23, 1967, I was a little girl wearing a pretty dress, attending my cousin’s wedding at a swanky hotel in mid-town Detroit. Driving home with my parents and sisters after the wedding, the radio news channel warned us of the blazing fires that were burning in a part of the city not far from where we were on a highway leading out to the suburbs.

On July 23, 1967, I was a little girl wearing a pretty dress, attending my cousin’s wedding at a swanky hotel in mid-town Detroit. Driving home with my parents and sisters after the wedding, the radio news channel warned us of the blazing fires that were burning in a part of the city not far from where we were on a highway leading out to the suburbs.

Fifty years and five days later, I am addressing the subject of health equity at a speech over breakfast at the American Hospital Association 25th Annual Health Leadership Summit today.

In my talk, I’ll connect the dots between me-as-a-child in ’67 Detroit to evolving as a health economist to work with clients on solutions underpinned by social determinants of health, to drive individual, population, and public health across America.

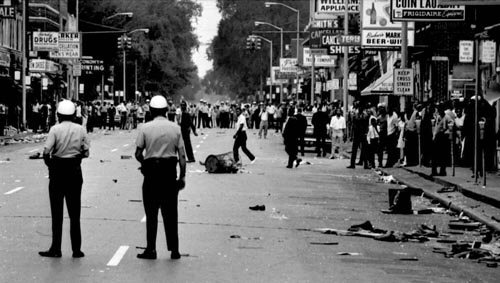

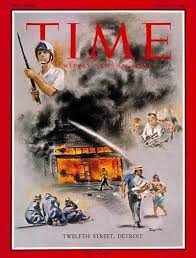

Picture me in the back seat of Daddy’s Mercury Monterey, him behind the wheel of the car driving us into the heart of what looked like war-torn streets to me sometime after the area calmed down….the looted stores, the smoky air, the neighbors cleaning up their neighborhoods…what I didn’t know is that 43 people would die as a result of the uprising and police response.

Picture me in the back seat of Daddy’s Mercury Monterey, him behind the wheel of the car driving us into the heart of what looked like war-torn streets to me sometime after the area calmed down….the looted stores, the smoky air, the neighbors cleaning up their neighborhoods…what I didn’t know is that 43 people would die as a result of the uprising and police response.

A few years later I was in junior high, reading a syllabus of books that included The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Why We Can’t Wait by Martin Luther King, and Black Boy by Richard Wright, among other works that continued to shape my maturing world-view.

Later in college, I took a course in Urban Economics from a professor whose teachings, ethos and spirit would shape me forever: Bill Neenan, PhD, was also known as William B. Neenan, SJ. “SJ?” some of you might ask. “Society of the Jesuits,” I would answer. Bill was that rare priest who did a PhD in economics and taught in the secular world of The University of Michigan’s department of economics just as I was considering a major in the subject. His book on urban economics is one of the main textbooks on the topic. His teaching, sense of humor, and outlook for good and hope profoundly informed my own approach to the subject, and ultimately, my professional path in health economics.

Fast-forward past twenty-plus years working with hospitals, health plans, clinicians, technology developers, consumer goods and electronics companies, financial services and non-profit organizations. Listening to and working with all these stakeholders in health over two+ decades has offered me another kind of education. Today, I share my most important learning with delegates to the AHA meeting: that social factors, and not so much healthcare, are the most important contributors to our community’s health and wellbeing.

Fast-forward past twenty-plus years working with hospitals, health plans, clinicians, technology developers, consumer goods and electronics companies, financial services and non-profit organizations. Listening to and working with all these stakeholders in health over two+ decades has offered me another kind of education. Today, I share my most important learning with delegates to the AHA meeting: that social factors, and not so much healthcare, are the most important contributors to our community’s health and wellbeing.

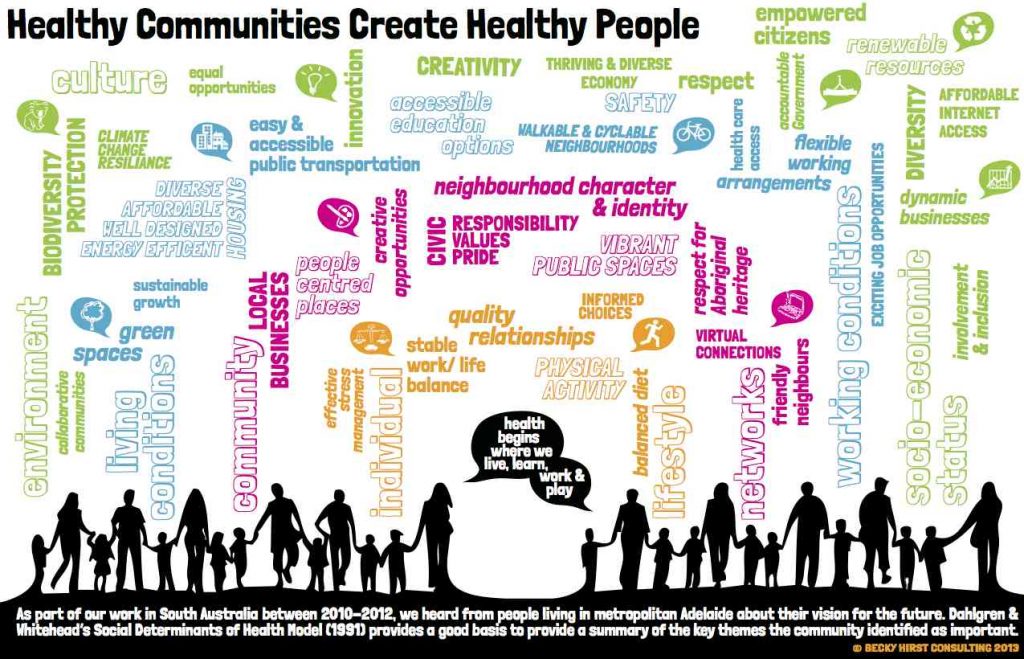

Those social determinants (SDOHs) are the aspects of daily living that impact us in our homes and communities where we live, work, play, pray and learn: living conditions, friendly neighbors and social connections, good and healthy food, clean water, safe neighborhoods, and, yes indeed, health care access (THINK: primary care, medicines, and early diagnosis among these inputs).

I like this illustration conceived by Becky Hurst of Adelaide, South Australia, where she works on community engagement strategies. Note that Becky includes “affordable internet access” in her SDOHs, along with climate change resilience and thriving and diverse economies.

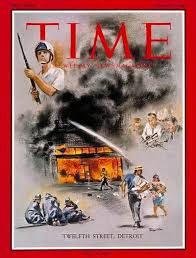

The streets around 12th and Claremont in Detroit erupted in July 1967 as a result of economic and social strife: job creation in the auto companies had slowed, and highways were built which enabled “white flight” out of the city into the suburbs and exurbs (including my own). The city of Detroit was plagued by a cocktail of negative social determinants which contributed to this event that would forever change my hometown.

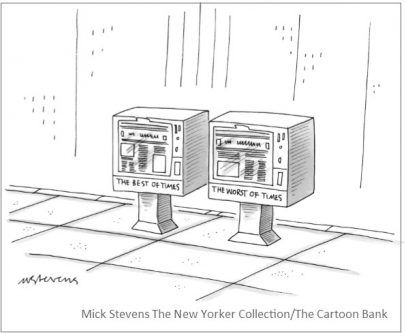

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I will point to this cartoon in my talk at the AHA meeting, noting we’re in The Best of Times and The Worst of Times. In healthcare, it feels like the worst of times as in the U.S., we are so challenged by the opioid crisis, costs spiraling, clinician burnout, and consumers health-financially insecure.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I will point to this cartoon in my talk at the AHA meeting, noting we’re in The Best of Times and The Worst of Times. In healthcare, it feels like the worst of times as in the U.S., we are so challenged by the opioid crisis, costs spiraling, clinician burnout, and consumers health-financially insecure.

It can also be the Best of Times for health — if we recognize, together, the role of social determinants to address root causes of healthcare woes and disparities. Health insurance is surely an on-ramp to health care access: it is necessary, but not sufficient, to deal with our health care challenges and public health inequities. I point to an article in JAMA (the Journal of the American Medical Association) published July 26, 2017, from Rita Rubin, looking at the “Half-century After ‘Summer of Love,'” where free clinics still play a vital role in American health care since evolving from 1967 when the Haight-Asbury Free Clinic was founded in San Francisco — 50 years ago.

Health can and must be baked into all policies, from food and transportation to housing and education. We can make health if we work collaboratively across the health/care ecosystem, and on Capitol Hill as well.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...