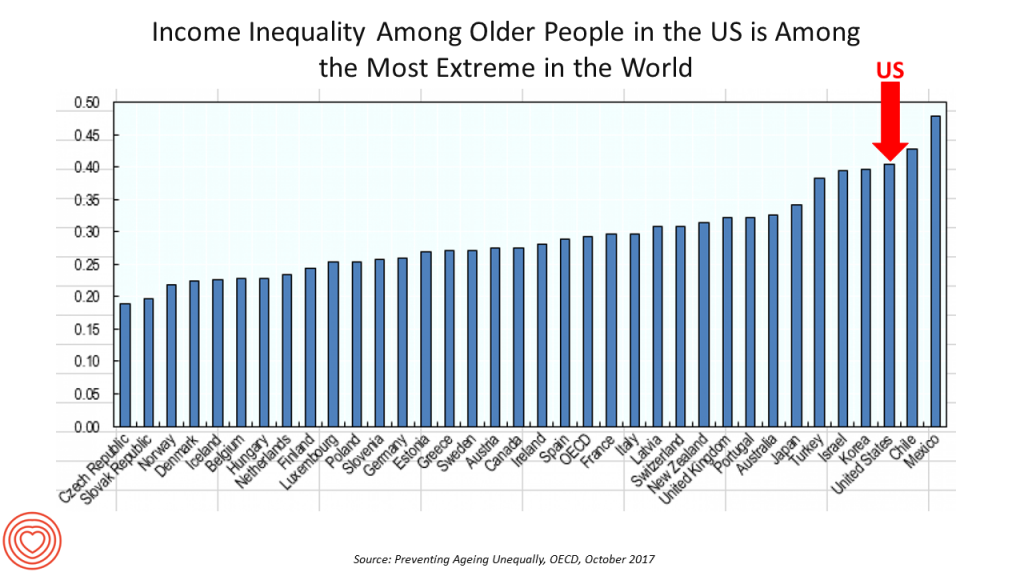

Old-age inequality among current retirees in the U.S. is already greater than in ever OECD country except Chile and Mexico, revealed in Preventing Ageing Unequally from the OECD.

Old-age inequality among current retirees in the U.S. is already greater than in ever OECD country except Chile and Mexico, revealed in Preventing Ageing Unequally from the OECD.

Key findings from the report are that:

- Inequalities in education, health, employment and income start building up from early ages

- At all ages, people in bad health work less and earn less. Over a career, bad health reduces lifetime earnings of low-educated men by 33%, while the loss is only 17% for highly-educated men

- Gender inequality in old age, however, is likely to remain substantial: annual pension payments to the over-65s today are about 27% lower for women on average, and old-age poverty is much higher among women than men.

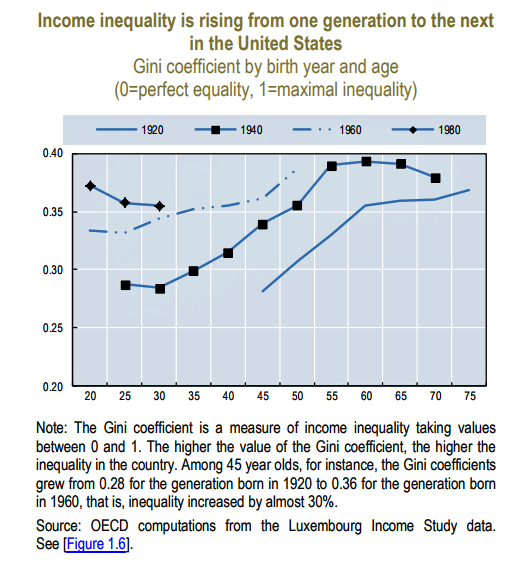

For economists, income inequality is expressed as the Gini coefficient: the greater the value of the Gini coefficient, the higher the inequality in a nation. In the U.S., the Gini coefficient has been rising from one American generation to the next since 1920, shown in the second chart.

For economists, income inequality is expressed as the Gini coefficient: the greater the value of the Gini coefficient, the higher the inequality in a nation. In the U.S., the Gini coefficient has been rising from one American generation to the next since 1920, shown in the second chart.

Health problems are a big reason contributing to increasing inequality. Americans are unhealthier than health citizens in other countries, particularly people earning lower incomes. “Disabilities, depression and obesity are widespread” in this group of people, the OECD observes. Over 1 in 3 Americans is obese, more than in any other OECD country.

To address this challenge, OECD offers three recommendations:

Prevent inequality before it grows over time, providing good childcare, early childhood education, cover healthcare early in a person’s life, and expanding youth work opportunities

Mitigate inequalities when they arise, through job services to get unemployed people back to work, targeting population health programs, and hiring older workers

Cope with older-age inequalities, like addressing women’s pension adequacy, ensuring affordable quality home care, and providing support for caregivers who perform high-value tasks for little to no economic benefit.

Here is a link to the OECD’s US report on income inequality in aging.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: “Health problems and employment disadvantages reinforce each other,” leading to more unhealthy poorer people, OECD warns. Policies can address the challenge of getting and keeping people healthy and in employment as long as possible, which boosts retirement incomes and mitigates poverty risks and “unequal aging.”

At this very moment, for example, the Children’s Health Insurance Program has yet to be re-authorized by the U.S. Congress. This program, founded in a bi-partisan way by Senators Edward Kennedy (Democrat) and Orrin Hatch (Republican), ensures that kids in America get access to health care — the kind of basic healthcare that the OECD asserts helps to prepare a citizenry for education and work, to contribute to society as full members (and taxpayers).

Other public policies can be designed to “bake” health into them, from food and transportation to housing and environmental standards. All of these social determinants influence health from birth.

Digital technologies can also help to support people’s social and health care in aging, and can address disparities and gaps in care. Dr. Joe Kvedar’s new book features innovations on the Internet of Healthy Things for aging and longevity. Remote health monitoring is gaining clinical-economic evidence to support people managing chronic conditions to live and age well at home, not in institutions — bringing down the total cost of care over the life-cycle and also enhance quality of life in one’s beloved surroundings. Intel’s announcement today in partnership with Flex in development of a Health Application Platform addresses this market, especially for remote health monitoring and the HealthIoT [I’ll be posting more on that in tomorrow’s Health Populi].

See Laurie Orlov’s Aging in Place Technology Watch, published, yesterday on the importance of “monitoring the person AND the place.” Here is her last paragraph which nails the design challenge:

“How about monitoring person and the place? While each solution categories by itself may useful, each is incomplete. On the body technologies should link to on-the-server hubs of useful health information for families and providers. In the (patient and care recipient) rooms, add the up-and-about wearables capturing and serving data that can follow the discharged patients into their homes and connect with any sensors placed there. Anomalies of behavior like falling or lack of motion are essential. Printed discharge instructions must be replaced with voice-first technologies that answer a person’s key questions: “Which pills am I supposed to take with food?” “What should I do if my heart starts skipping beats?” “When is the ride pickup for my follow-up appointment?” “Please ask my son to call me – now.” We’re not there yet in terms of what older adults need – and it’s not for lack of technology. And it is a shame.”

Here’s a great infographic published in concert with the Connected Health Conference, Dr. Kvedar’s longtime meet-up addressing digital health, now part of HIMSS and the Personal Connected Health Alliance.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...