The phenomenon of Deaths of Despair is the short-hand name for rising mortality among certainly people living in the U.S. due to overdose, accidents, and suicide. Angus Deaton and Anne Case published their first of many research papers on Deaths of Despair in 2015. Their research uncovered the risks of dying a Death of Despair to be higher among men, especially those between the ages of 25 and 64.

But mortality isn’t only going in the wrong direction for those people most closely associated with the Deaths of Despair demographic: there’s another life-span line graph moving in the wrong direction, and it’s for young Americans under 19 years of age.

s

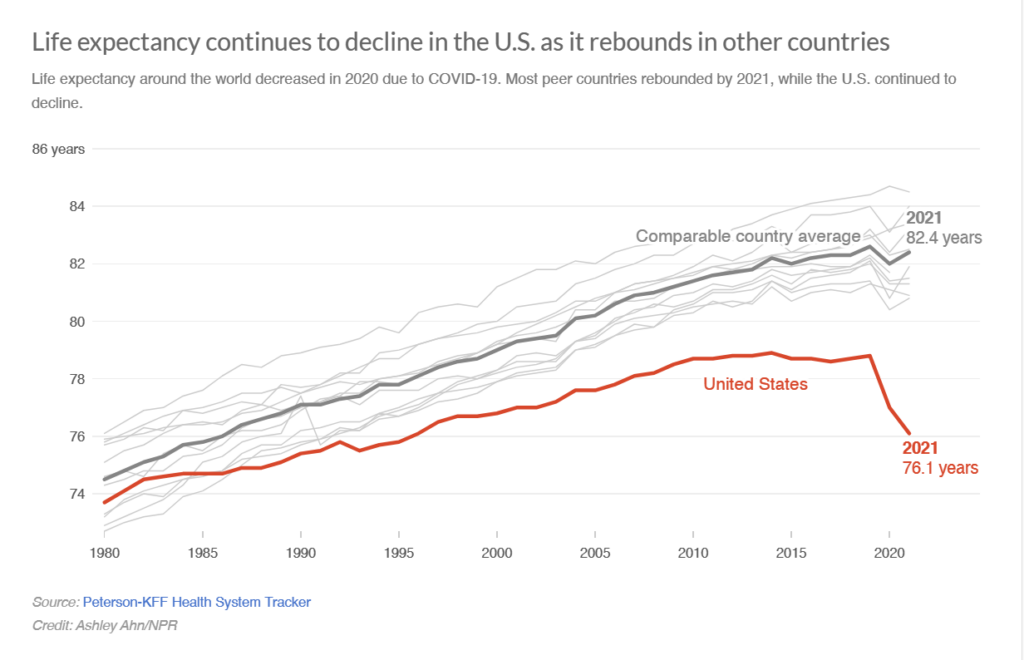

NPR broadcast a Morning Edition story titled “Live Free and Die” on March 25th. Subtitled “the sad state of U.S. life expectancy,”

The declining curve here represents U.S. life expectancy for all residents of all ages of 76.1, some 6+ years lower than comparable country averages the OECD has collected for Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada,, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K.

For more on the Deaths of Despair in the U.S., you can search through the Health Populi blog for my various takes — starting with the milestone research of Deaton and Case discussed in this post.

Now we turn to a JAMA viewpoint published on March 13 titled The New Crisis of Increasing All-Cause Mortality in US Children and Adolescents. Dr. Steven Wolf and colleagues write about, quote, “A nation that begins losing its most cherished population — its children — faces a crisis like no other.”

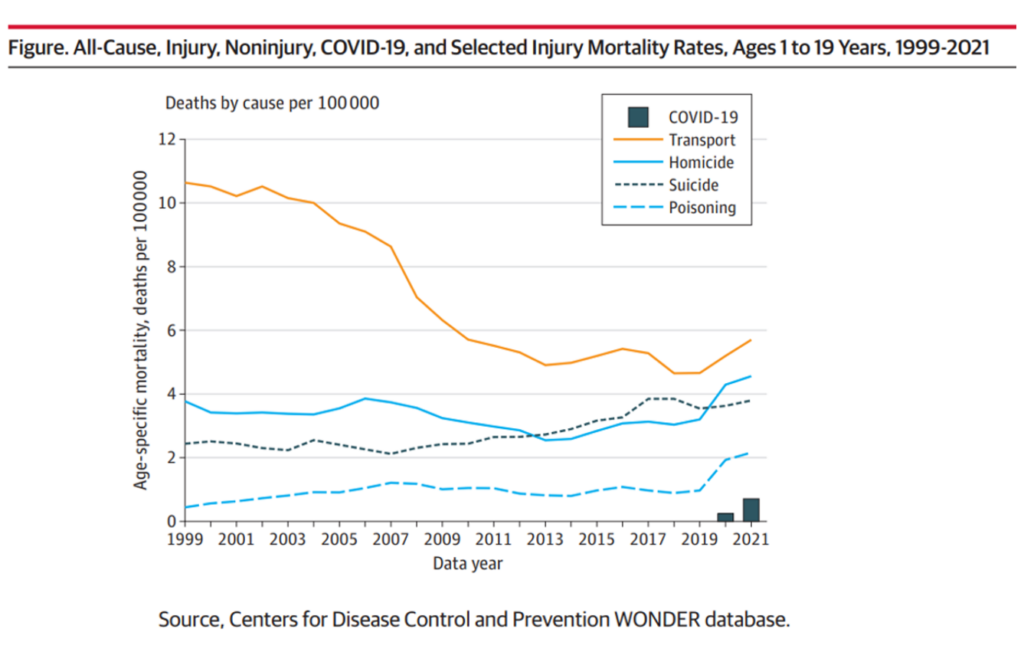

Here is the line graph Dr. Woolf et al. featured in their essay. This chart graphs the mortality rates per 100,000 people between ages 1 and 19 years old by five causes: COVID-19, transport accidents (i.e., death by car, bus, train, etc.), homicide, suicide, and poisoning.

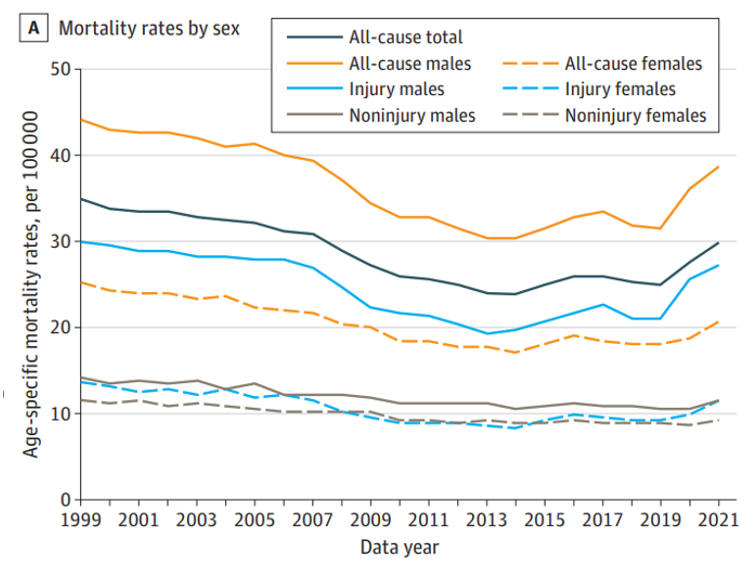

Death rates for young Americans increased across all five categories. Today I’m pointing to homicide, the solid aqua blue line, in the graph.

Note that these data go to 2021, so do not include the life expectancy data for young Americans from 2022 or first quarter of 2023.

The increase in pediatric injury deaths was not caused by COVID-19 but due to injuries, the authors note. But the pandemic “may have poured fuel on the fire,” they observe.

“Much of this surge involved homicides, which increased by 39.1%, and deaths from drug overdoses, which increased by 113.5%.”

Gains in kids’ life expectancy (say, for pediatric cancer and congenital disorders) improved young peoples’ mortality rates; we can see the graph’s declining mortality rates here, by cause. The mortality rates for people ages 1 to 19 continued to fall from 1999 until about 2013, when deaths due to injury took a turn up and to the right — especially among young males.

“Firearms play a central role in this crisis,” one of the concluding paragraphs asserts. “They are the leading cause of death among youths aged 1 to 19 years old and accounted for nearly half of the increase in all-cause mortality in 2020.”

Bullets, drugs, and automobiles are now causing a youth death toll sufficient to elevate all-cause mortality rates, they conclude.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: “Without bold action to reverse the trend, children’s risk of not reaching adulthood may increase.”

That’s Dr. Woolf’s and colleagues’ last sentence of the succinct 2-page JAMA viewpoint.

The piece was published on March 13, two weeks before yesterday’s Nashville mass shooting at the Covenant Presbyterian Church School killing three children and older victims.

Last week, I received a mailing from my local hospital system, Main Line Health. I cut out a phrase from the marketing piece that resonated with me — “Human care means seeing our neighbors.”

This came to front of mind now as I wrestle and think about the data from the CDC, OECD, and the JAMA viewpoint on “losing our most cherished population:” our children.

Human care really does mean seeing our neighbors.

So does public policy and legislation. We are all health citizens, every day.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...