Anne Case and Angus Deaton were working in a cabin in Montana the summer of 2014. Upon analyzing mortality data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, they noticed that death rates were rising among middle-aged white people.

“We must have hit a wrong key,” they note in the introduction of their book, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism.

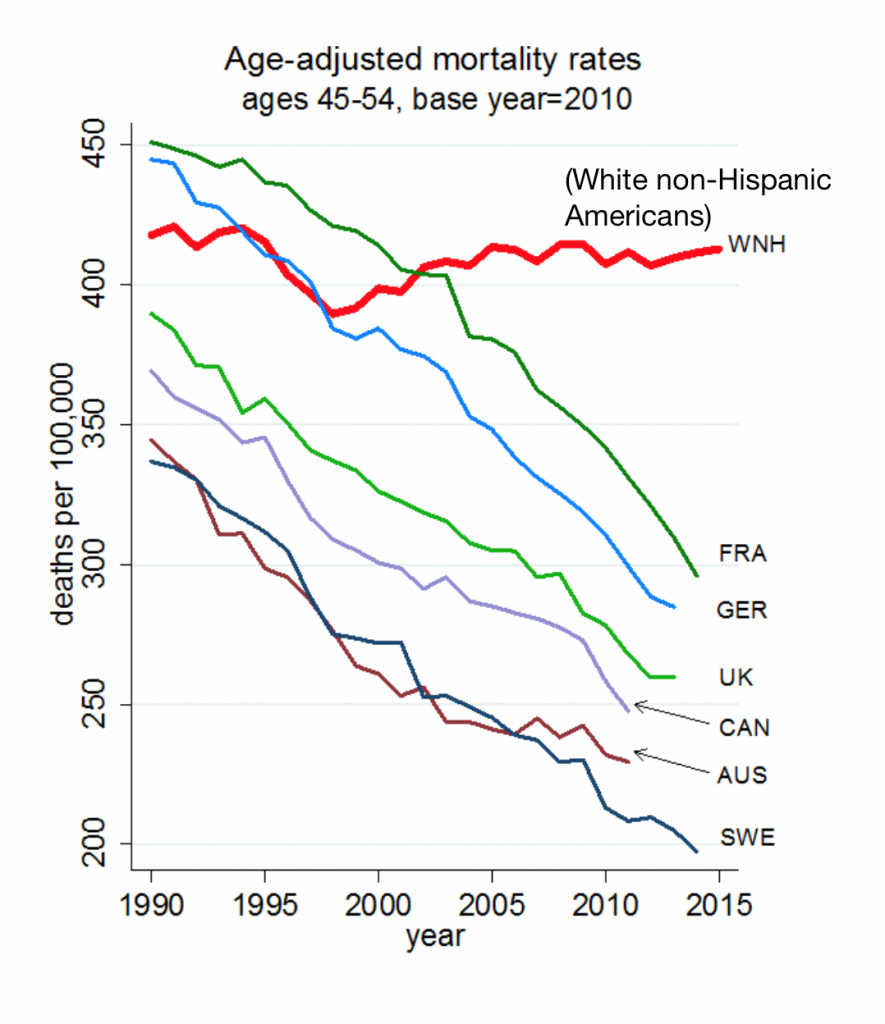

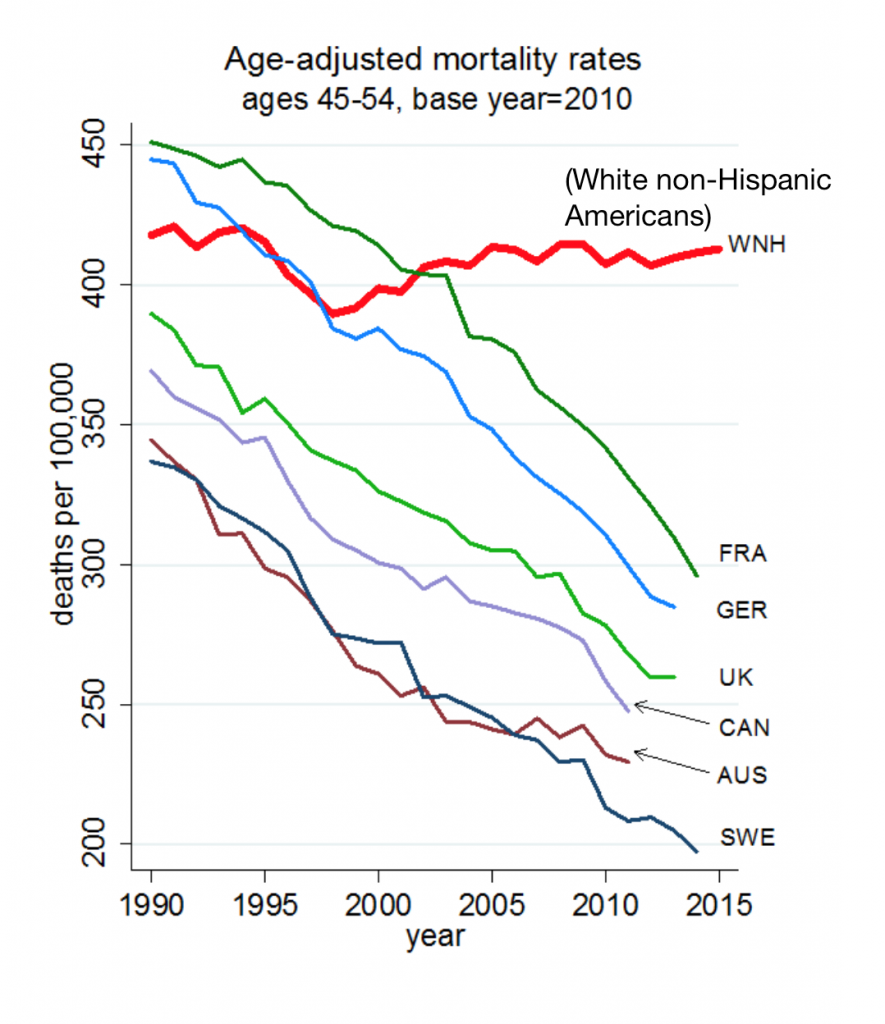

This reversal of life span in America ran counter to a decades-long trend of lower mortality in the U.S., a 20th century accomplishment, Case and Deaton recount.

In the 300 pages that follow, the researchers deeply dive into and weave the data through different demographic and clinical lenses — race, gender, age, social connectedness, work history, and the most important through-line: education.

“We tell the story, not only of death, but of pain and addiction and of lives that have come apart and have lost their structure and significance. For Americans without a B.A., marriage rates are in decline, though cohabitation and child-bearing are not. Many middle-aged men to not know their own children….The comfort that used to come from organized religion…is now absent from many lives. People have less attachment to work; man are out of the labor force altogether, and fewer have the long-term commitment to an employer whom in turn, was once committed to them, a relationship that, for many, conferred status and was one of the foundations of a meaningful life.”

“We tell the story, not only of death, but of pain and addiction and of lives that have come apart and have lost their structure and significance. For Americans without a B.A., marriage rates are in decline, though cohabitation and child-bearing are not. Many middle-aged men to not know their own children….The comfort that used to come from organized religion…is now absent from many lives. People have less attachment to work; man are out of the labor force altogether, and fewer have the long-term commitment to an employer whom in turn, was once committed to them, a relationship that, for many, conferred status and was one of the foundations of a meaningful life.”

Thus Case and Deaton connect the dots, literally, in the many charts that explain what factors are driving the Deaths of Despair — lives lost to accidental deaths, suicide and drug overdoses. Here’s one included in the beginning of the book that’s a macro-picture of U.S. illustrating the reversal of life-span benefits for white non-Hispanic Americans compared to mortality declines in France, Germany, the UK, Canada, Australia and Sweden.

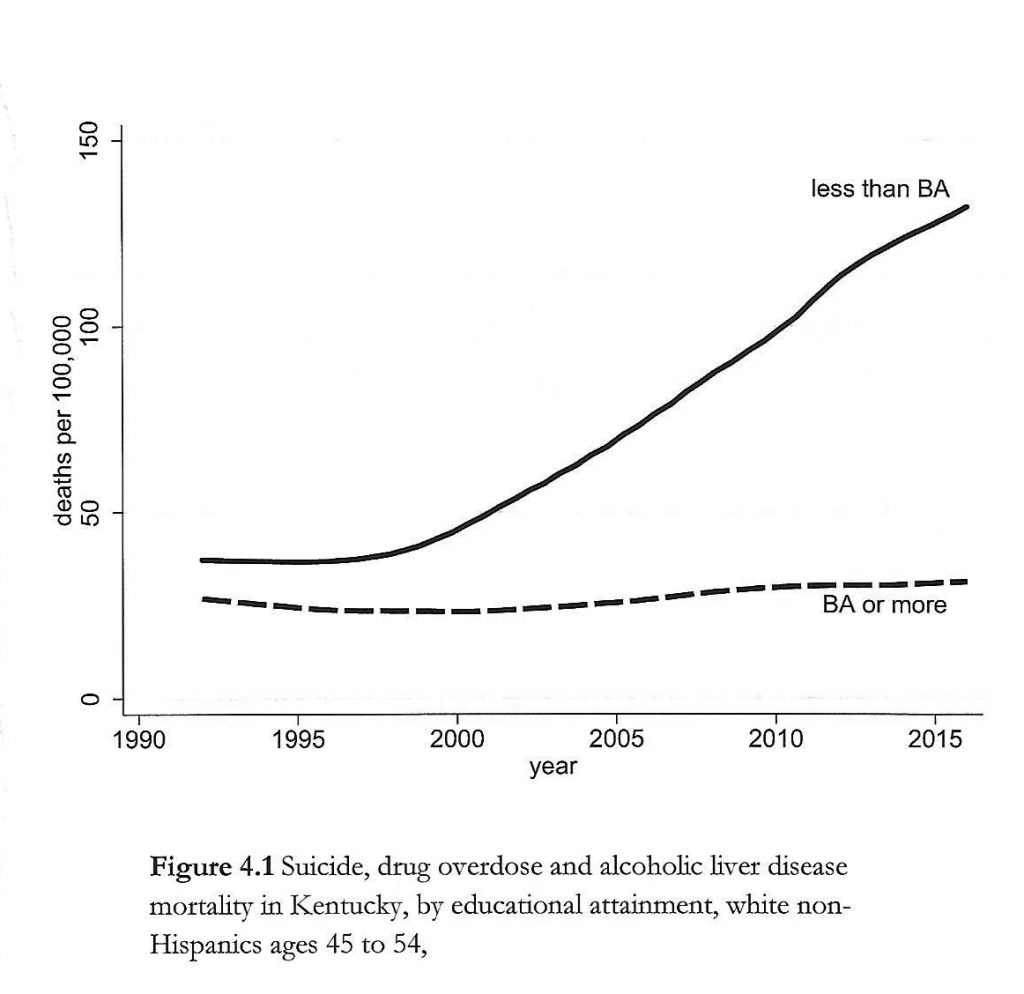

Now look at this graph, illustrating suicide, drug overdose and alcoholic liver disease mortality in Kentucky by educational attainment for white non-Hispanic people ages 45 to 54.

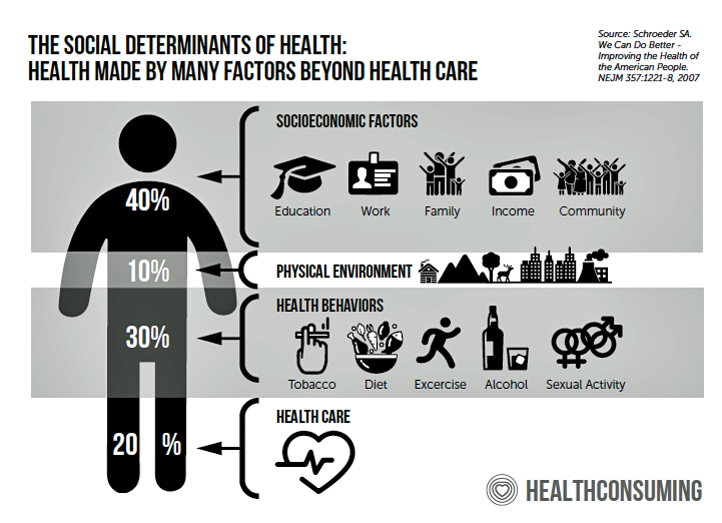

The mantra that “your ZIP code is more important than your genetic code” has gone mainstream (and it’s a key pillar in my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumers to Health Citizens. Chapter 7 of the book is called, “ZIP Codes, Genetic Codes, Food, and Health,” and speaks to the chasms between, say, McCreary County KY (with a median income around $20,000) and Loudon County VA (whose median income at $140,000 ranks #1 in the U.S.). The food systems and wage levels, along with available health care services and quality of air and water, substantially vary in each of these two counties.

The mantra that “your ZIP code is more important than your genetic code” has gone mainstream (and it’s a key pillar in my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumers to Health Citizens. Chapter 7 of the book is called, “ZIP Codes, Genetic Codes, Food, and Health,” and speaks to the chasms between, say, McCreary County KY (with a median income around $20,000) and Loudon County VA (whose median income at $140,000 ranks #1 in the U.S.). The food systems and wage levels, along with available health care services and quality of air and water, substantially vary in each of these two counties.

So is the educational attainment levels achieved by each area’s residents: 7% of MacCreary County citizens hold a B.A. or higher. Sixty percent of residents in Loudon Co. have at least a Bachelor’s degree. That’s a huge difference, and that makes a difference in the deaths of despair.

There are other factors Case and Deaton have uncovered in their research: in addition to education, the key social determinant of health which is in fact “being social” and feeling connected to other people is a key ingredient of a fulfilled life.

“As religions faltered, opioids became the opium of the masses,” Case and Deaton describe. Peoples’ attendance at religious services is one key form of social connection on a regular basis. As peoples’ participation in organized religion and participating in weekly services has waned, this has contributed to folks’ declining time spent with other people — a declining factor found in the latest OECD report, How’s Life 2020: Measuring Well-Being.

The book Bowling Alone brilliantly documented the decline in social capital toward the end of the 20th century, and Case and Deaton build on Robert Putnam’s seminal work in Deaths of Despair.

Cigna has been studying the growing loneliness epidemic, and this blue graphic comes from their latest report in loneliness published in January 2020.

Six in 10 people in the U.S. reported feeling lonely in 2019 with folks saying they don’t have enough social support, with too few meaningful interactions, poor physical and mental health, and insufficient balance in one’s life, Cigna learned.

“There are 330 million Americans, yet we’re lonely and getting lonelier,” Cigna concluded.

Making their evidence-based argument documenting the growing phenomenon of Deaths of Despair, Case and Deaton move to the topic of how the U.S. economy has recently exacerbated the situation. The decline of unions, growing prevalence of technology and telecommuting, expanding gig economy, and eroding safety net have created the perception for millions of Americans that capitalism in 2020 has failed them.

“The villains are not globalization and automation themselves,” Case and Deaton explain, “but the way that America is dealing with them.” How to make a better deal for the American worker? More regulation in the public interest, and public policies that help citizens “get back to prosperity and good health,” asserts the last sentence in the book.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I draft this post on Monday 9th March 2020. Today will eventually be painted with an epithet akin to “Black Monday” when the stock market’s dive resulted in a “circuit breaker” to halt trading for part of the day.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I draft this post on Monday 9th March 2020. Today will eventually be painted with an epithet akin to “Black Monday” when the stock market’s dive resulted in a “circuit breaker” to halt trading for part of the day.

Today’s plummeting market has been blamed on the coronavirus’s global impact and anxiety hitting investors and regular people alike who lack information and clarity about the nature of the virus in their local communities and how the pandemic could impact jobs, livelihoods and, fundamentally, lives.

In the U.S., a key social determinant of health is access to health care services. While we generally focus attention of SDOH pillars on food, transportation, and housing, health care access is indeed one of the SDOH must-haves.

There’s a self-reinforcing scenario in the U.S. given (1) our lack of universal health care and (2) the lack of a social safety net for people in the gig economy and those earning lower incomes in jobs lacking health insurance coverage. According to this report released yesterday from the Economic Policy Institute, people in the U.S. who need sick days the most are least able to get them.

The very people who earn an hourly wage without insurance can’t afford to take off time from work to either get tested for COVID-19, or stay home to recuperate from the virus which in younger people could be amenable to simply staying home, resting, ingesting liquids, and “self-quarantining.”

When pandemics are involved, we are all in the same lifeboat, regardless of political ID, ethnicity or education level. A virus, an active organism like COVID-19, doesn’t distinguish between a Republican, an Independent, or a Democrat; a Christian, a Muslim or a Jew; or someone in Loudon County earning $140,000 a year.

For more data from Deaths of Despair, explore these interactive charts embedded in David Leonhardt’s story on Case and Deaton’s research in the New York Times.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...