Yesterday, IQVIA presented their end-of-year data based on medical claims in the U.S. health care system tracking the ups, downs, and ups of the coronavirus in America. IQVIA has been tracking COVID-19 medical trends globally from early 2020.

The plotline of patient encounters for vaccines, prescribed medicines, foregone procedures and diagnostic visits to doctors begs the question: in 2021, will Americans be “sicker,” discovering later-stage cancer diagnoses, higher levels of pain due to delayed hip procedures, and eroded quality of life due to leaky guts?

The plotline of patient encounters for vaccines, prescribed medicines, foregone procedures and diagnostic visits to doctors begs the question: in 2021, will Americans be “sicker,” discovering later-stage cancer diagnoses, higher levels of pain due to delayed hip procedures, and eroded quality of life due to leaky guts?

Here are a few snapshots that paint a picture for greater morbidity and potentially more “excess deaths,” mortality, due to health care postponed in the U.S.

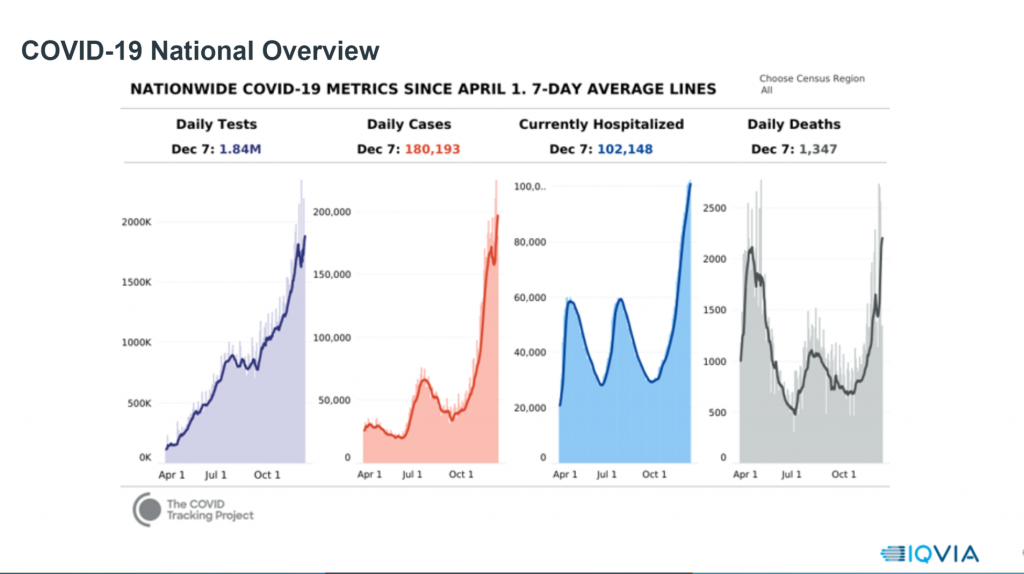

The first graph pictures a national overview of COVID-19, illustrating the upward trajectory of testing, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. The case graph makes it clear that the U.S. never had a reprieve from the coronavirus. The hospital admissions graph in blue tracks the initial burst of inpatients, the decline in the early summer, then apex after the July 4th holiday, autumnal decline, and exponential shot up in the current moment, when many hospitals across the U.S. and state governors are warning the supply of beds, hardware (e.g., ventilators), and “software” (say, PPE in the form of N95 masks) are strained.

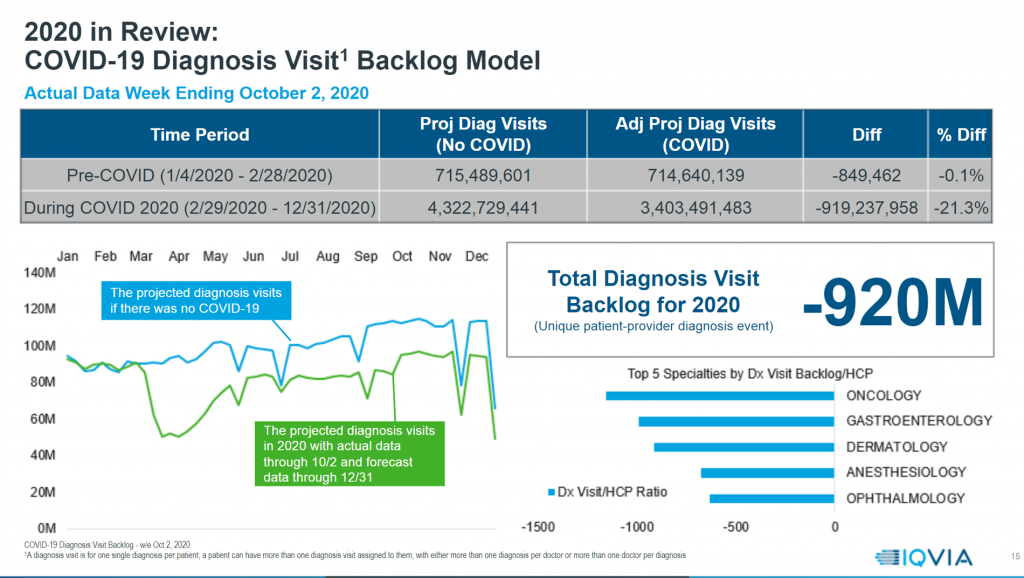

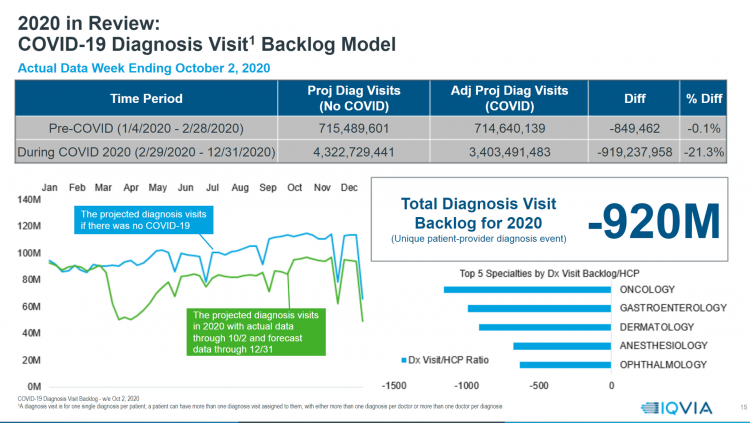

That’s the hospital, inpatient context which sets the stage for the next data point: diagnosis “backlog.” IQVIA modeled what would have been expected in terms of patient visits for diagnosing all health conditions, compared with actual medical claims for patients during COVID-19.

That’s the hospital, inpatient context which sets the stage for the next data point: diagnosis “backlog.” IQVIA modeled what would have been expected in terms of patient visits for diagnosing all health conditions, compared with actual medical claims for patients during COVID-19.

This comparison resulted in a net backlog, or deficit, of 21% fewer diagnosis visits. That amounts to about 920 million fewer patient diagnostic encounters [about 1,100 fewer diagnostic visits per provider]. The blue line at the left is what would have been without COVID-19 for diagnosis visits; the green line underneath shows the actual data through October 2nd and a forecast through year-end 2020.

The top five specialties with backlog for diagnoses were oncology, gastroenterology, dermatology, anesthesiology, and ophthalmology.

Specifically, IQVIA believes that 15% of the oncology diagnosis visits will not happen this year.

Anesthesiology declines have to do with postponed elective surgery.

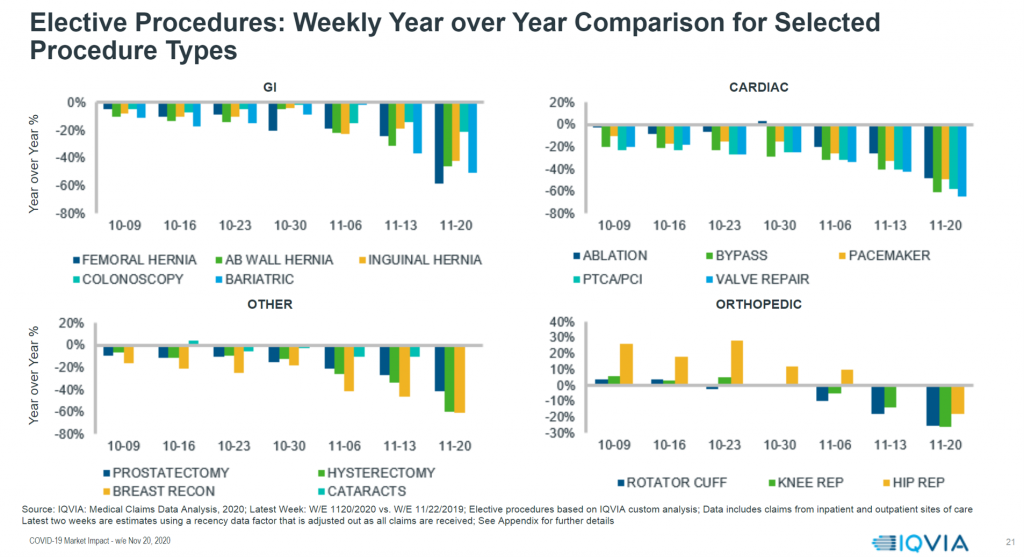

To that point, the third graph here details specifics about elective procedures for GI, cardiac, orthopedic, and other categories.

As your eyes move from left to right, you see the decline year-over-year of so-called “elective” procedures from October to late November 2020. These include hernia procedures and colonoscopies in the GI category, heart procedures like bypass and valve repairs under cardiac, orthopedic procedures like hip and knee replacements, and prostatectomies under “other,” among many other surgical codes and patient complaints.

In this post, I’ve shared with you just three slides from IQVIA’s much more comprehensive look at COVID-19’s impact on the U.S. health care delivery system. You can access the entire IQVIA broadcast to learn more about prescriptions foregone, telehealth volumes compensating in part for some outpatient visits not seen in doctor’s offices and clinics, vaccines delivered (more in peds than adults), and other claims lines illustrating postponed and missed patient visits in America.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Through the snapshots of three diagrams I selected here, I’m highlighting the “backlog problem” which may prevent the U.S. from “getting back to the kind of health status and health care delivery we used to have,” as Michael Kleinrock of the IQVIA Institute explained through the medical claims data he explored in the webcast.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Through the snapshots of three diagrams I selected here, I’m highlighting the “backlog problem” which may prevent the U.S. from “getting back to the kind of health status and health care delivery we used to have,” as Michael Kleinrock of the IQVIA Institute explained through the medical claims data he explored in the webcast.

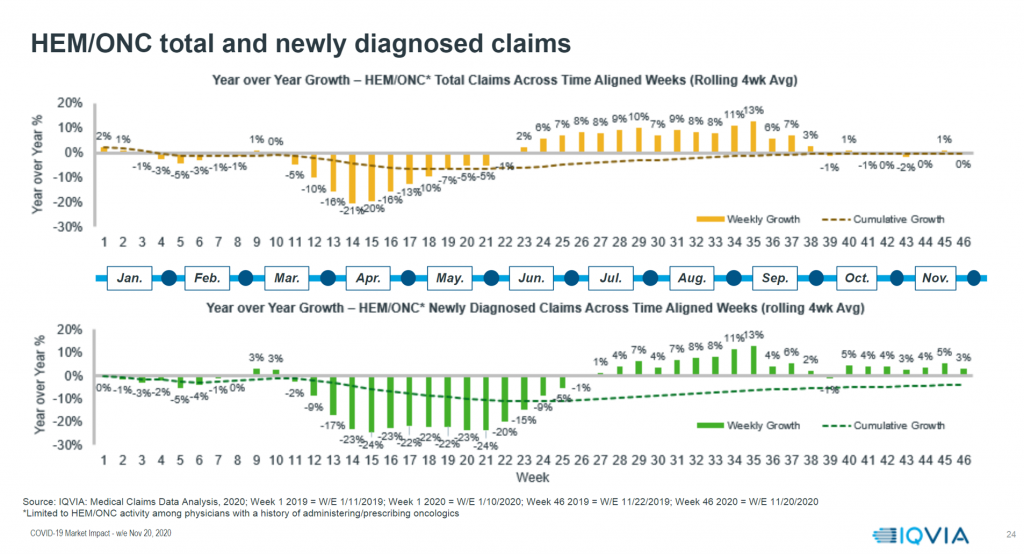

Early diagnosis foregone means later diagnosis and advanced illness for some patients.

Take the specific issue of cancer: the hematology/oncology specifics shown in the fourth chart here from IQVIA’s claims data give us pause, especially looking at the deep decline in year-on-year newly diagnosed claims (the green vertical bars in weeks 12 through 25) and weak return to expected visits that, as Kleinrock would term, “the kind of delivery we used to have.”

Now consider the third graph, above, showing the specific elective procedures delayed. Here, we can imagine people in pain, in distress, in discomfort, or postponed diagnoses of colon cancer that would have been caught earlier through a colonoscopy.

Will 2021 see more patients in the U.S. sicker, in greater pain, and generating greater costs for delayed care? You now know that’s one of the probable scenarios in my look into the new year for American health care.

Thanks to IQVIA for your important data collection effort and analysis through the 2020 phase of the coronavirus pandemic.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...