“The odds are against hospitals collecting patient balances greater than $7,500,” the report analyzing Hospital collection rates for self-pay patient accounts from Crowe concludes.

Crowe benchmarked data from 1,600 hospitals and over 100,00 physicians in the U.S. to reveal trends on health care providers’ ability to collect patient service revenue.

And bad debt — write-offs that come out of uncollected patient bill balances after “significant collection efforts” by hospitals and doctors — is challenging their already-thin or negative financial margins.

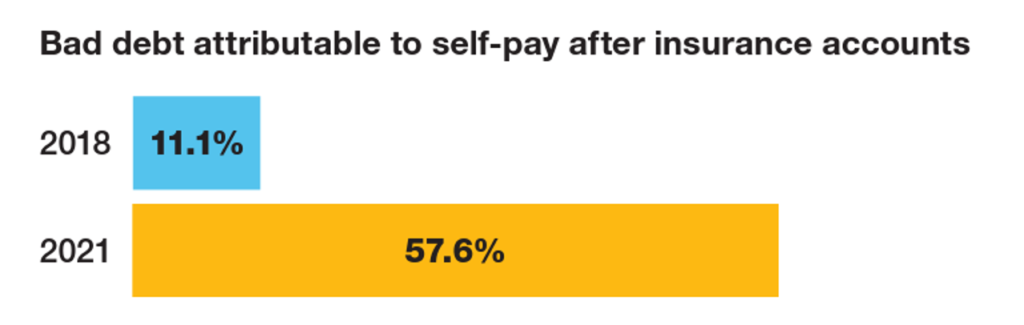

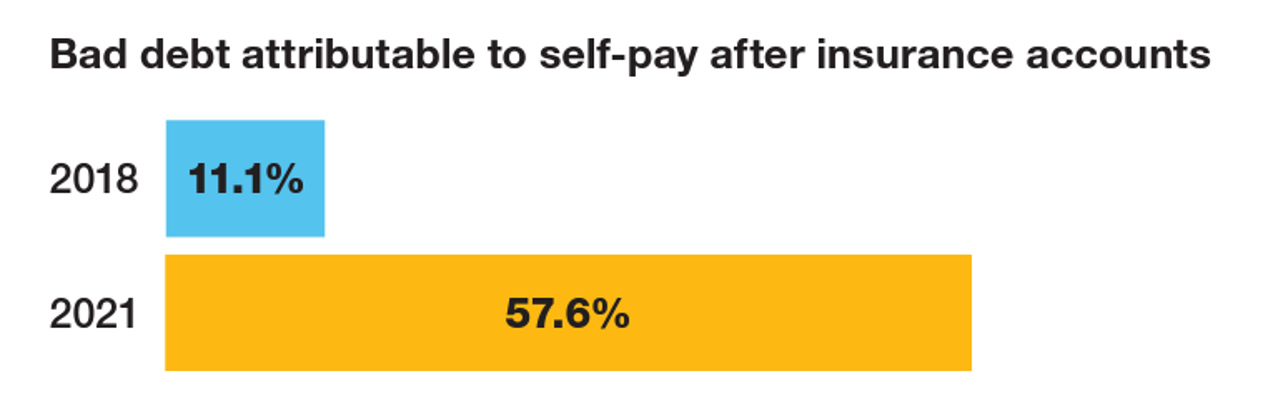

The first chart quantifies that bad debt attributable to patients’ self-pay payments after insurance kicks in: that category of bad debt grew by five times between 2018 and 2021, from 11% to nearly 58%.

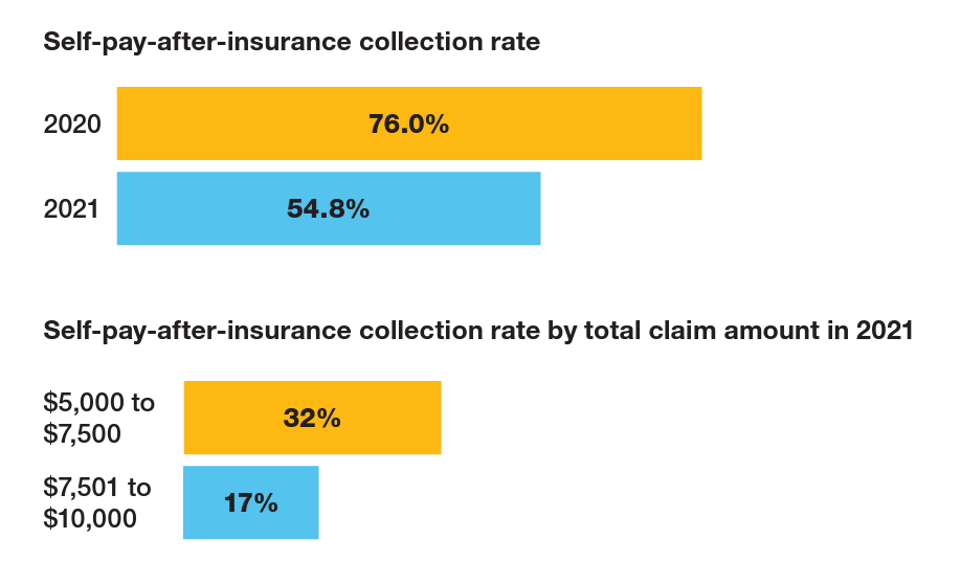

Collection rates for the bad debt fell from 76% in 2020 to 55% in just the one year from 2020 to 2021, a drop of nearly one-third.

Now see the third bar chart, self-pay after insurance collection rate by total claims amount in 2021: here is where we see the “vanishing point” of $7,500:

- One-third of the self-pay-after-insurance claim amount was collection that fell between $5,000 and $7,500

- Only 17% of that amount was collected falling between $7,501 and $10,000, Crowe calculated.

The bottom line in this analysis is that, “the increased number of high0-dedutbiel health plans…has changed the makeup of what it means to have health insurance coverage,” Crowe explains.

For more hospitals, “the change just means the hospitals have to collect more from the patient,” not from the insurance company.

“It’s one thing to ask patients for the $75 or even $200 copay amounts at the point of service,” Brian Sanderson of Crowe’s healthcare practice explained in the report. “It’s a completely different conversation to guide them through paying thousands of dollars.”

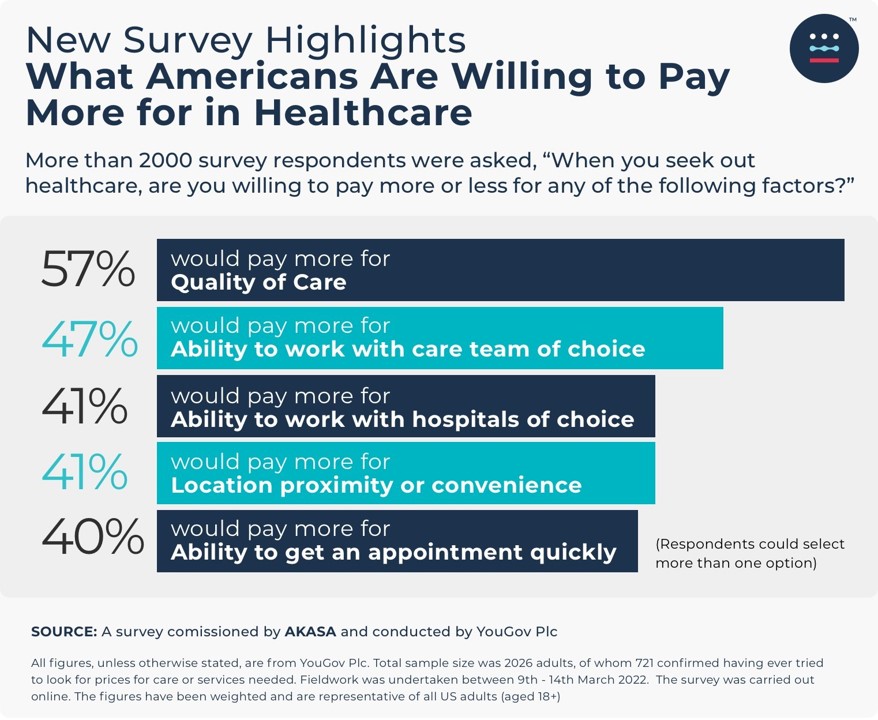

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Another interesting study was published this month from AKASA on what U.S. patients would be willing to pay more for in health care, leaving aside the pragmatic question of what type of health insurance plan design the consumer had.

In the YouGov survey, most patients said they would be willing to pay more for quality of care, and nearly one-half would pay more for choosing the medical team for their care.

So, patients-as-payers and health consumers told AKASA, which is in the business of revenue cycle management, that quality and choice were worth a premium or enhanced charge on their medical bill.

Nonetheless, “the quality of care is often diminished by the less-than-stellar patient financial experience,” Amy Raymond, VP of revenue cycle operations at AKASA, said in response to this finding.

That’s the patient side of this story on bad debt and hypothetical willingness-to-pay for quality and choice.

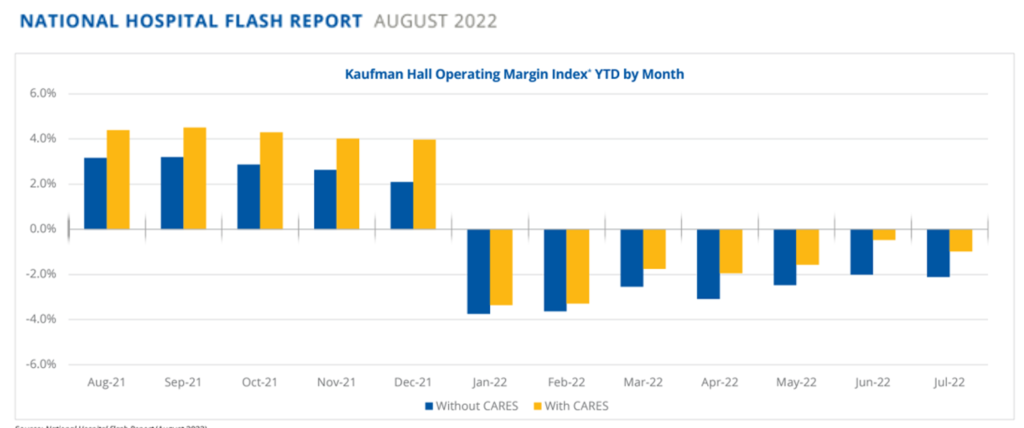

The reality side of the coin for hospitals is that financial margins, six months into 2022, are in the red, according to Kaufman Hall’s August 2022 Hospital Flash Report.

Furthermore, FitchRatings’ latest analysis of Healthcare and Pharma Credit Rounds: 2Q22, a special report published September 1, 2022, said that “rating actions (are) increasingly negative” in healthcare.

For the hospitals segment, Fitch called out the fact that inpatient capacity is still constrained by staffing shortages and that providers are focusing on improving operations, containing cots, and negotiating commercial rate increases that could keep up with inflation. “These measures are likely to take several quarters, if not longer, to achieve the targeted effects,” Fitch cautioned.

For some strategic counsel on this tough situation for U.S. hospitals and systems, let’s turn to Dr. Robert Pearl’s latest post in Forbes magazine titled, Saving US Healthcare From a Disaster Worse Than Covid-19.

Dr. Pearl’s perfect storm of 3 mega forces include,

- Healthcare inflation, expecting medical costs to grow by double-digits in 2023

- The nursing shortage, calling out that the vast majority of nurses are considering leaving the profession int he next year; and

- The burnout crisis, noting that nearly half of physicians feel over-worked and under-appreciated, and that more hospital-based docs are turning to private equity firms to firm up their negotiating heft.

The opportunity, Dr. Pearl outlines, is to work quite quickly on three lower-hanging fruit areas that can make a big difference in increasing access, reducing costs, and improving clinicians’ satisfaction:

- To invest in people — in particular, staff that can streamline surgical suite workflow, radiology/imaging functions, and procedural suites like those that do colonoscopies, to improve throughput and productivity.

- To “eliminate 10,000 steps,” which is the concept of re-designing nurse and other providers’ physical coverage to save time

- Build team excellence through creating specialized teams that are super-productive, super-efficient, delivering super-high quality and outcomes.

Dr. Pearl’s proposals can address both sides of this dire coin of bad debt and quality aspirations which negatively impact both patients and their clinicians and hospital systems.

But this is going to take a lot of collaboration and negotiation and community to pull off: all for the objective of saving our hospitals and communities’ access to health care services.

The larger ecosystem health/care market trend is that with patients-as-payers, hospitals are facing retail-style pressures for designing both service and financial experiences that patients value.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...