In the current state of the COVID-19 pandemic, we all feel like we are living in desperate times.

If you are a person at-risk of dying a Death of Despair, you’re even more at-risk of doing so in the wake of the Coronavirus in America.

If you are a person at-risk of dying a Death of Despair, you’re even more at-risk of doing so in the wake of the Coronavirus in America.

Demonstrating this sad fact of U.S. life, the Well Being Trust and Robert Graham Center published Projected Deaths of Despair from COVID-19.

The analysis quantifies the impact of isolation and loneliness combined with the dramatic economic downturn and mass unemployment with the worsening of mental illness and income inequity on the epidemic of Deaths of Despair.

The term “deaths of despair” was coined by Anne Case and Angus Deaton in their ground-breaking research which culminated in their March 2020 book, Deaths of Despair.

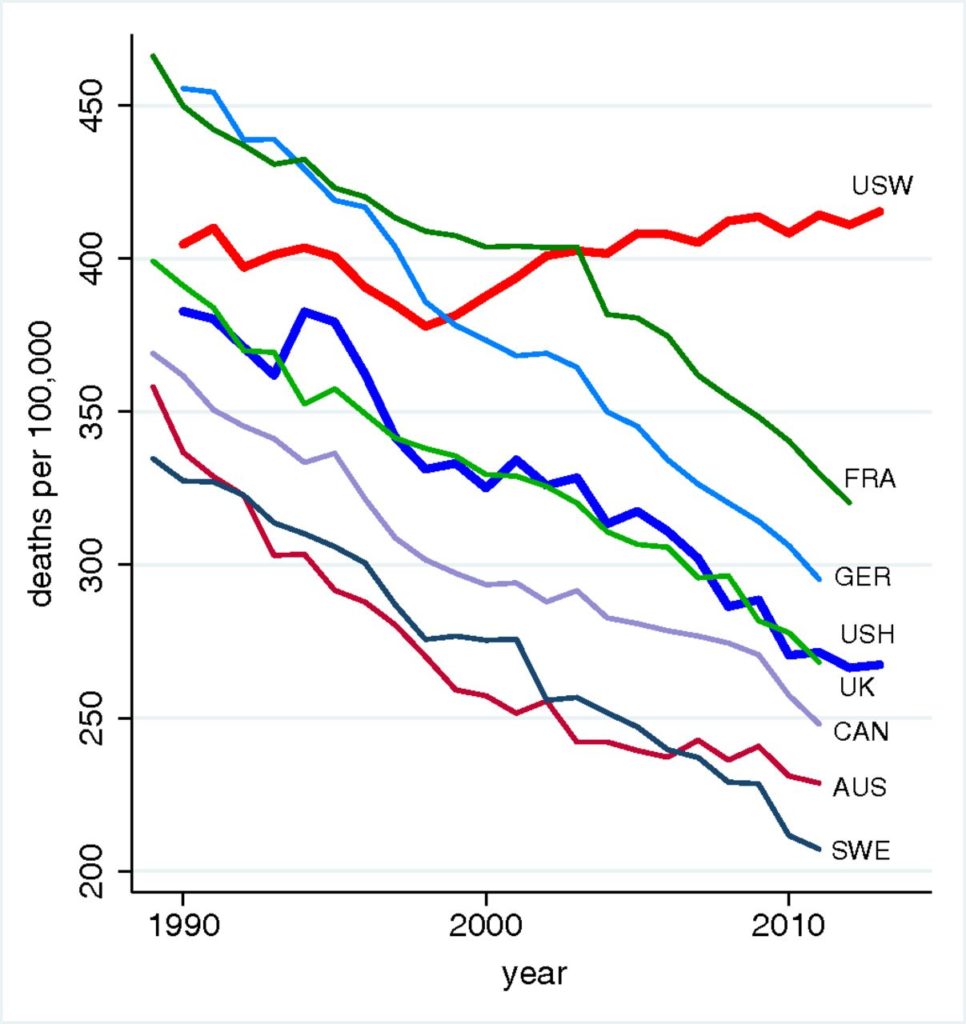

Deaths of despair are the rising mortality rates in the U.S. due to suicide, accidents and drug overdoses first observed by Case and Deaton in a seminal 2015 paper, “Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century.” The first line chart illustrates the rising death rates per 100.000 people for U.S. “W”hites versus declining death rates for people from France, Germany, the UK, Canada, Austria, and Sweden, along with U.S. “H”ispanics.

Unemployment was among several risk factors for this rising death rate, along with lower education levels, social isolation, and other factors co-mingled with work and wage inequality.

“We are seeing many of (these) disparities play out in real time during COVID-19,” the report notes.

The quick, sad math of this phenomenon is that a 1 point increase in unemployment rates increases U.S. suicide rates by 1% to 1.6%.

The quick, sad math of this phenomenon is that a 1 point increase in unemployment rates increases U.S. suicide rates by 1% to 1.6%.

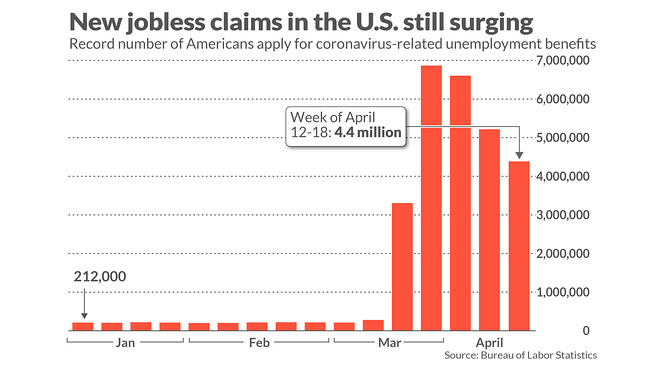

With that arithmetic in mind, consider the lightning-speed loss of over 20 million jobs in the U.S. between March and early May 2020.

Carrying through this tough math, the unemployment rate rose to nearly 15% as of early May, up from under 4% in January 2020. This is roughly a delta of 11%.

Based on the 1% rise in unemployment, we could expect an 11% rise in the number of people who take their life, just from this early financially toxic phase of the pandemic.

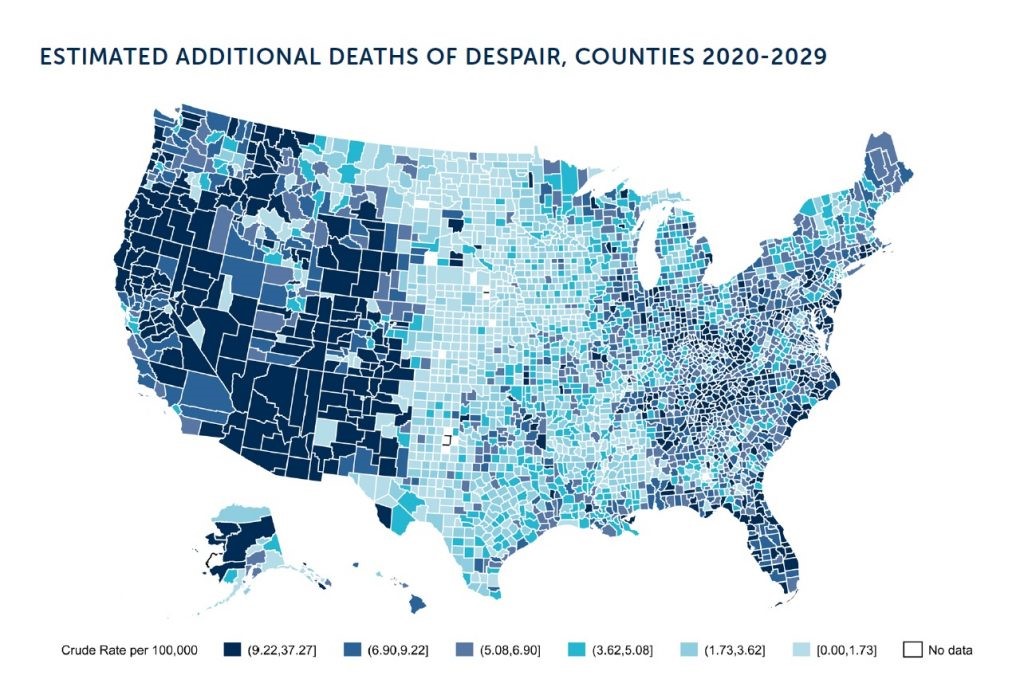

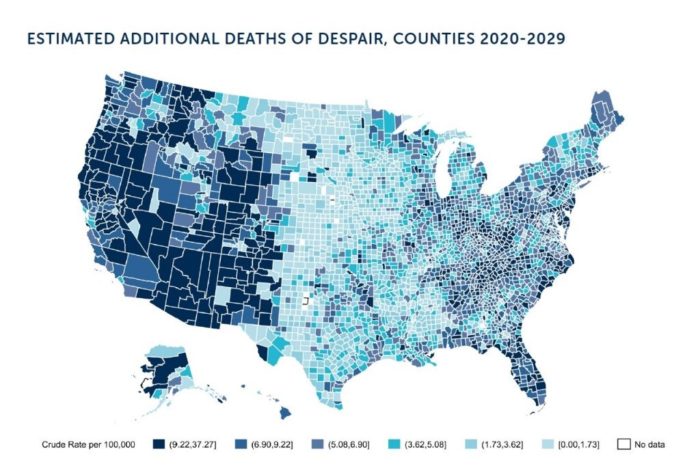

With this research as context, the Well Being Trust-Graham Center project modeled the impact of COVID-19 on deaths of despair making assumptions about the U.S. economy, the level of unemployment, and geographic variation of the impact. The model incorporated cause of death data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) classification system.

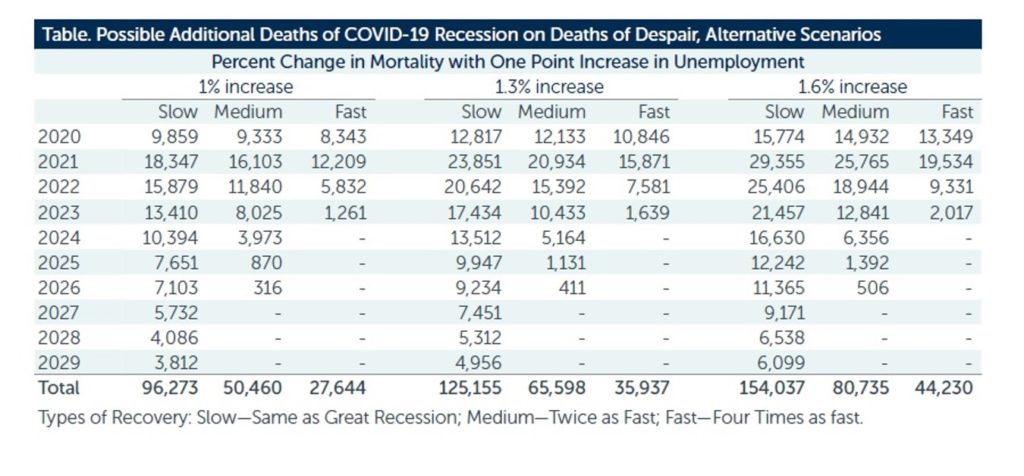

This table summarize three scenario forecasts of possible additional deaths due to COVID-19 based on 3 different estimates of rates: 1%, 1.3% and 1.6%. Each of these changes in mortality rates was coupled with a percent changes in unemployment and a rate of national economic recovery of “slow,” “medium,” or “fast.”

This table summarize three scenario forecasts of possible additional deaths due to COVID-19 based on 3 different estimates of rates: 1%, 1.3% and 1.6%. Each of these changes in mortality rates was coupled with a percent changes in unemployment and a rate of national economic recovery of “slow,” “medium,” or “fast.”

Assuming a 1% increase in mortality with a one point increase in unemployment and a fast economic recovery, some 27,000 Americans would die a death of despair.

If the economy would recover slowly, the high end for deaths of despair would be close to 100,000 Americans. At the highest estimated death rate of 1.6% and a slow recover, the deaths of despair would exceed 150,000. WBT and Graham Center opine that, “considering the negative impact of isolation and uncertainty, the 1.6% multiplier may be more accurate” than the low 1% assumption.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: What COVID-19 has done is to highlight health disparities and underlying structural flaws in the U.S. health system, the Well Being Trust and Center conclude in the report. People who have been at highest risk for losing a job or being exposed to COVID-19 communities were already at a higher risk of mortality.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: What COVID-19 has done is to highlight health disparities and underlying structural flaws in the U.S. health system, the Well Being Trust and Center conclude in the report. People who have been at highest risk for losing a job or being exposed to COVID-19 communities were already at a higher risk of mortality.

To manage these risks, the reporters do not recommend a fast return-to-work or immediate stop to physical distancing.

The policy prescriptions WBT and the center recommend are to:

- Get people working, providing training, identifying new opportunities to employ people in unique workforces like COVID-19 tracking and tracing

- Get people connected via virtual platforms — but attending to the problem of many rural and other communities lacking internet access to support video connections. This solution could involve local non-profit organizations, faith-based institutions, and community touchpoints

- Integrate mental health with health care

- Get facts and science out to people in well-designed, articulated formats that will engage and best communicate with people where they “are”

- Offer a vision for the future of health care, especially integrating mental health and addiction services into workflow and financing, and

- Get people care — primary care, mental health care, and specialty care that addresses the evidence that some people with chronic and serious conditions have avoided care due to fear of being exposed to the virus, due to cost, or both.

Ultimately, the report points out the critical learning that the U.S. must, “move aggressively toward solutions that bring mental health into the center of all our discussions on COVID-19 response and recovery.”

For further insights into Case and Deaton’s important work, read more here about their book, and here for how social determinants of health underpin avoidable mortality in America.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...