The financial toxicity of health care costs in the U.S. takes center stage in Health Populi this week as several events converge to highlight medical debt as a unique feature in American health care.

“Medical debt is the most common collection tradeline reported on consumer credit records,” the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau called out in a report published March 1, 2022. CFPB published the report marking two years into the pandemic, discussing concerns about medical debt collections and reporting that grew during the COVID-19 crisis.

Let’s connect the dots on:

- A joint announcement this week from three major credit agencies, agreeing to eliminate about 70% of medical debt from consumer credit reports

- A report from the American Cancer Society‘s Cancer Action Network on cancer and medical debt, and,

- The report from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau on the medical debt burden in the United States.

Start with the groundbreaking plan struck between Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion who jointly agreed as of July 1, 2022, to exclude paid medical collection debt from consumers’ credit reports. The agencies will also extend the time period before unpaid medical collection debt appears on credit reports from six months to one year, allowing consumers in medical debt to work with health care providers and plans to deal with debt before it is reported. Finally, in the first six months of 2023, the three agencies will no longer include medical collection debt under $500 on consumers’ credit reports.

Start with the groundbreaking plan struck between Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion who jointly agreed as of July 1, 2022, to exclude paid medical collection debt from consumers’ credit reports. The agencies will also extend the time period before unpaid medical collection debt appears on credit reports from six months to one year, allowing consumers in medical debt to work with health care providers and plans to deal with debt before it is reported. Finally, in the first six months of 2023, the three agencies will no longer include medical collection debt under $500 on consumers’ credit reports.

“Medical collection debt often arises from unforeseen medical circumstances. These changes are another step we’re taking together to help people across the United States focus on their financial and personal wellbeing,” the three CEOs of the companies are quoted.

Next, consider the specific role of cancer costs and financial toxicity, quantified in Survivor Views: Cancer & Medical Debt from the Cancer Action Network. In this survey conducted among patients and survivors dealing with cancer in February 2022, most people said they were unprepared for what the costs of their care would be. As a result, most made major changes to their lifestyles and finances.

Next, consider the specific role of cancer costs and financial toxicity, quantified in Survivor Views: Cancer & Medical Debt from the Cancer Action Network. In this survey conducted among patients and survivors dealing with cancer in February 2022, most people said they were unprepared for what the costs of their care would be. As a result, most made major changes to their lifestyles and finances.

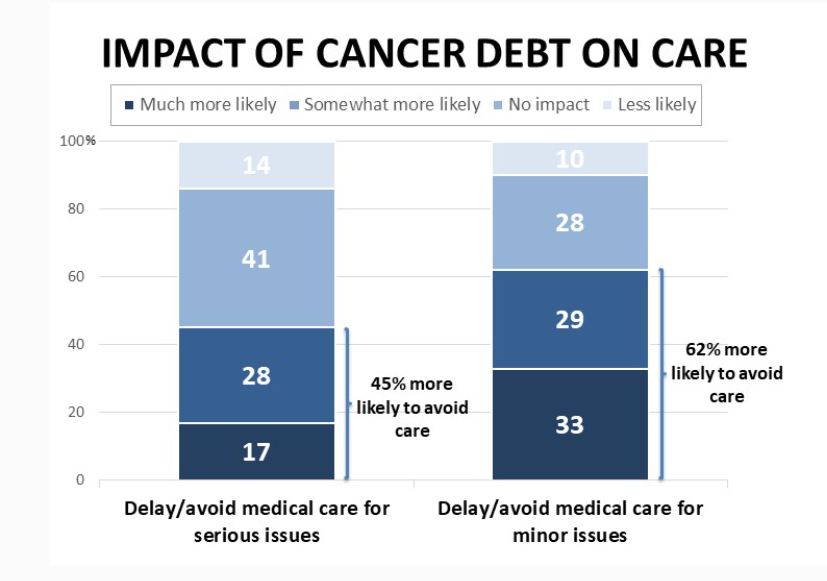

Medical debt in cancer can hinder patients’ seeking care as well as limit their treatment options, the study found. About 1 in 2 people who had medical debt delayed or avoided medical care for serious issues, and one-half also sought the least expensive treatment options due to the debt they were carrying.

As with many aspects of U.S. health care, disparities persist in cancer care and medical debt: African-Americans were more likely to report having medical debt associated with cancer treatment, and more likely were contacted by collections agencies regarding the debt. Cancer patients living in state that had not yet or only recently expanded Medicaid also were more likely to report medical debt and being less prepared for the costs of cancer care.

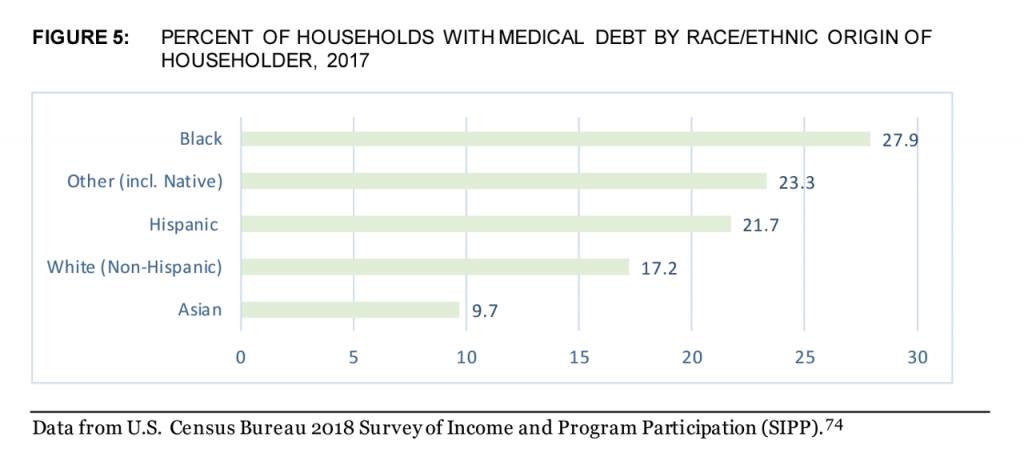

The CFPB report also examined households with all medical debt by race and ethnic origin of the householder. The chart with the green bars demonstrates that Black Americans were more than 50% more likely to have medical debt than Whites. Hispanic households fell in-between White and Black households for medical debt, with Asian householders least likely to have medical debt burden their family budgets.

The CFPB report also examined households with all medical debt by race and ethnic origin of the householder. The chart with the green bars demonstrates that Black Americans were more than 50% more likely to have medical debt than Whites. Hispanic households fell in-between White and Black households for medical debt, with Asian householders least likely to have medical debt burden their family budgets.

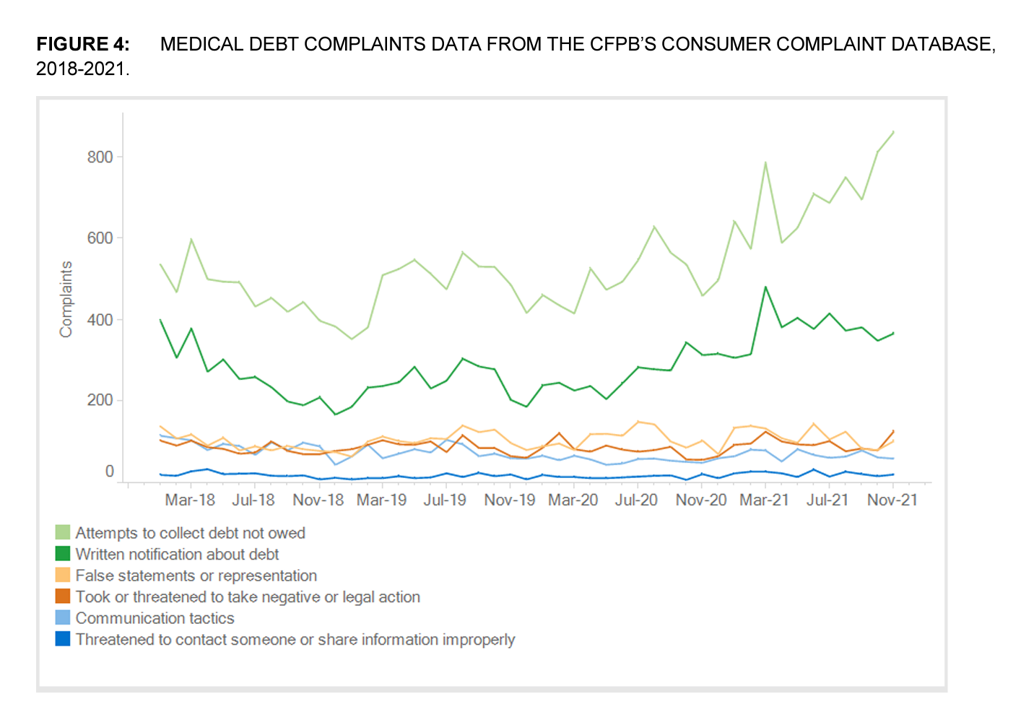

Consumers’ complaints about medical debt collectors spiked way up during the COVID-19 pandemic, as shown in the line chart.

These complaints were especially onerous on consumers with collection agencies attempting to collect debt not owed and for written notifications about debt.

These complaints were especially onerous on consumers with collection agencies attempting to collect debt not owed and for written notifications about debt.

The bottom-line of CFPB’s report is that:

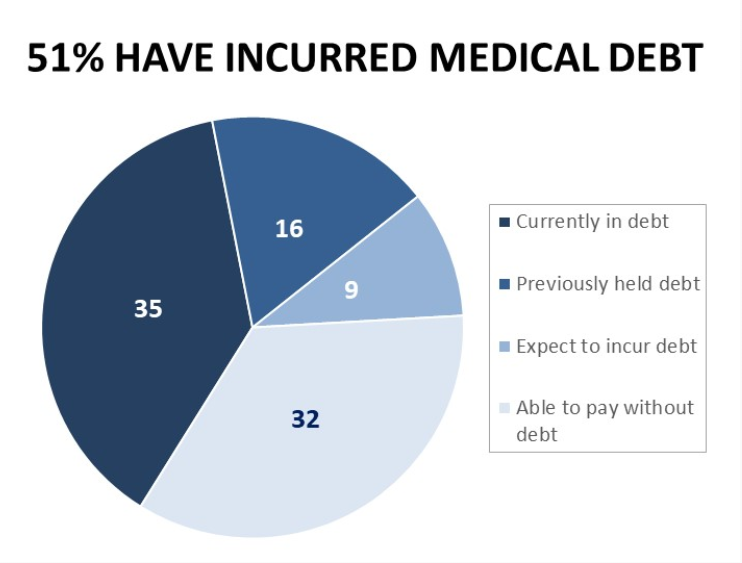

- Medical debt impacts tens of millions of U.S. households, about one in five; and,

- COVID-19 exacerbated medical debt in America.

CFPB’s recommendations were to…

- Hold credit reporting companies accountable for reasonable procedures

- Work with Federal partners to reduce coercive credit reporting, and

- To determine whether unpaid medical billing data should be included in credit reports.

We come full circle with this third recommendation from CFPB with the Equifax-Experian-TransUnion plan to reduce most medical debt from patients’ credit reports.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The concept of financial toxicity was raised in a 2014 60 Minutes segment during which correspondent Lesley Stahl spoke with Dr. Leonard Saltz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Saltz was speaking as chief of the department of gastrointestinal oncology.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The concept of financial toxicity was raised in a 2014 60 Minutes segment during which correspondent Lesley Stahl spoke with Dr. Leonard Saltz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Saltz was speaking as chief of the department of gastrointestinal oncology.

Dr. Saltz noted that the general price for a new oncology drug was “well over $100,000 a year,” adding that the price was only for one therapy and that other costs can push the total cost of therapy for a year up to a quarter of a million dollars.

Stahl asked Dr. Saltz,

“So, are you saying in effect, that we have to start treating the cost of these drugs almost like a side effect from cancer?”

To which Dr. Saltz responded,

“I think that’s a fair way of looking at it. We’re starting to see the term ‘financial toxicity’ being used in the literature. Individual patients are going into bankruptcy trying to deal with these prices.”

Eight years since that segment aired on CBS, financial toxicity has become a major challenge for families dealing with cancers and other diagnoses — toxic for household budgets and credit scores as well as for self-rationing health care.

The last bar chart shown here comes from the Survivor Views survey from the American Cancer Society, done in February 2022. Note that 45% of patients with cancer debt were more likely to avoid medical care for serious issues than people without debt. And 62% of those with cancer debt were more likely to avoid care for minor issues.

The study also found variation in terms of race/ethnicity and where people lived: those cancer patients residing in states whose governors chose not to expand Medicaid were worse off in terms of debt than people living in Medicaid-expansion states.

So here’s a case, once again, where one’s ZIP code portends at least as much for health and care as one’s genetic code or pre-disposition to cancer risks. We term those issues social determinants of health; in this case, the subset is simply put a financial determinant of health.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...