While health care has been slower than other industries to leverage digital transformation, COVID-19 accelerated change — revealing some key barriers blocking the potential for more fulsome transformation, the OECD explains in its latest version of Health At A Glance for 2023 with a detailed chapter on “digital health at a glance.”

The OECD report assesses digital health maturity across 22 countries: in addition to the U.S., the report provides details digital health traits in (alphabetically) Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Scotland (UK), Slovenia, and Sweden.

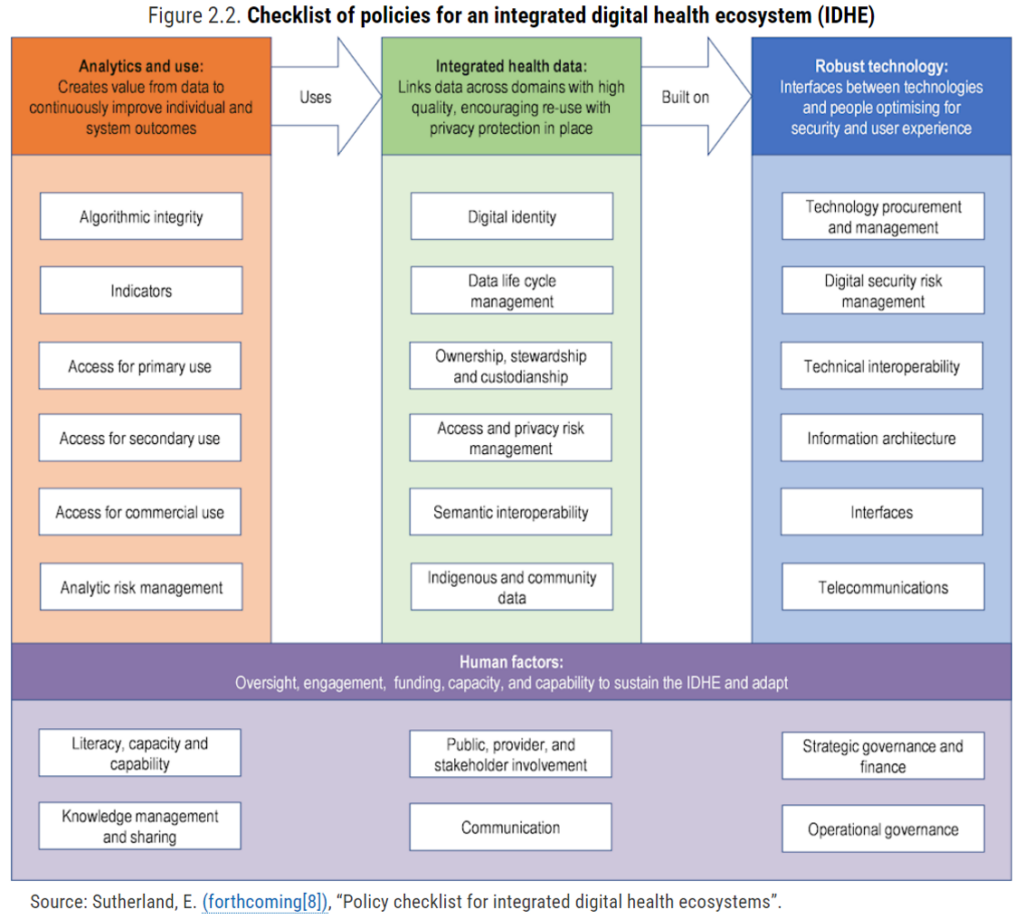

The definition of “digital health” has not been set in stone (don’t we know it!) and so the OECD first, rightly, sets a comprehensive context for this assessment setting out a checklist of policies for an integrated health system shown here. This is quoted from a forthcoming publication from Dr. Eric Sutherland, senior health economist with the OECD.

Digital health encompasses four dimensions: analytic readiness (analytics and use), data readiness (linking data across domains/integration), technology readiness (e.g., inteoperability as well as security), and human factor readiness, which addresses digital literacy, citizen and stakeholder involvement, and trust.

Among the many aspects we could explore in Health Populi, I’ve chosen two that are most top-of-mind for my work these days: interoperability and AI, comparing US to the peer OECD nations.

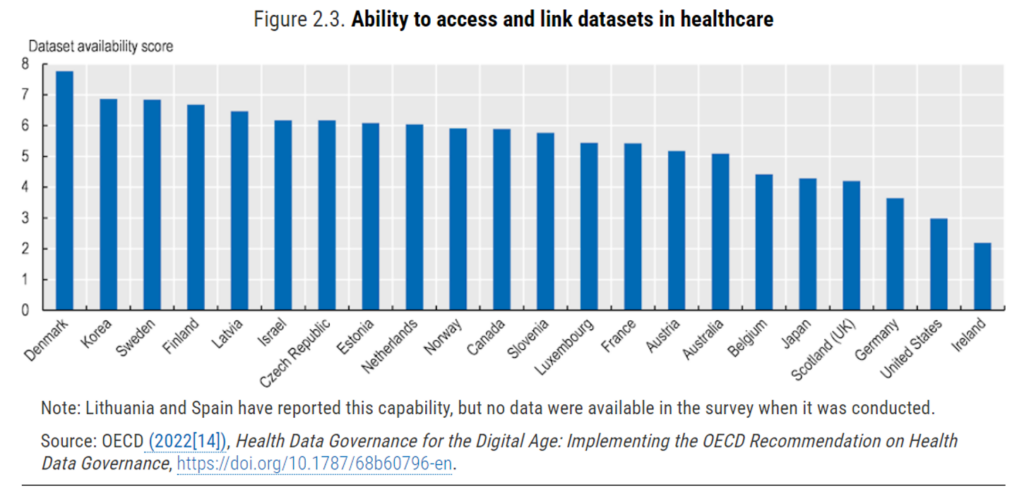

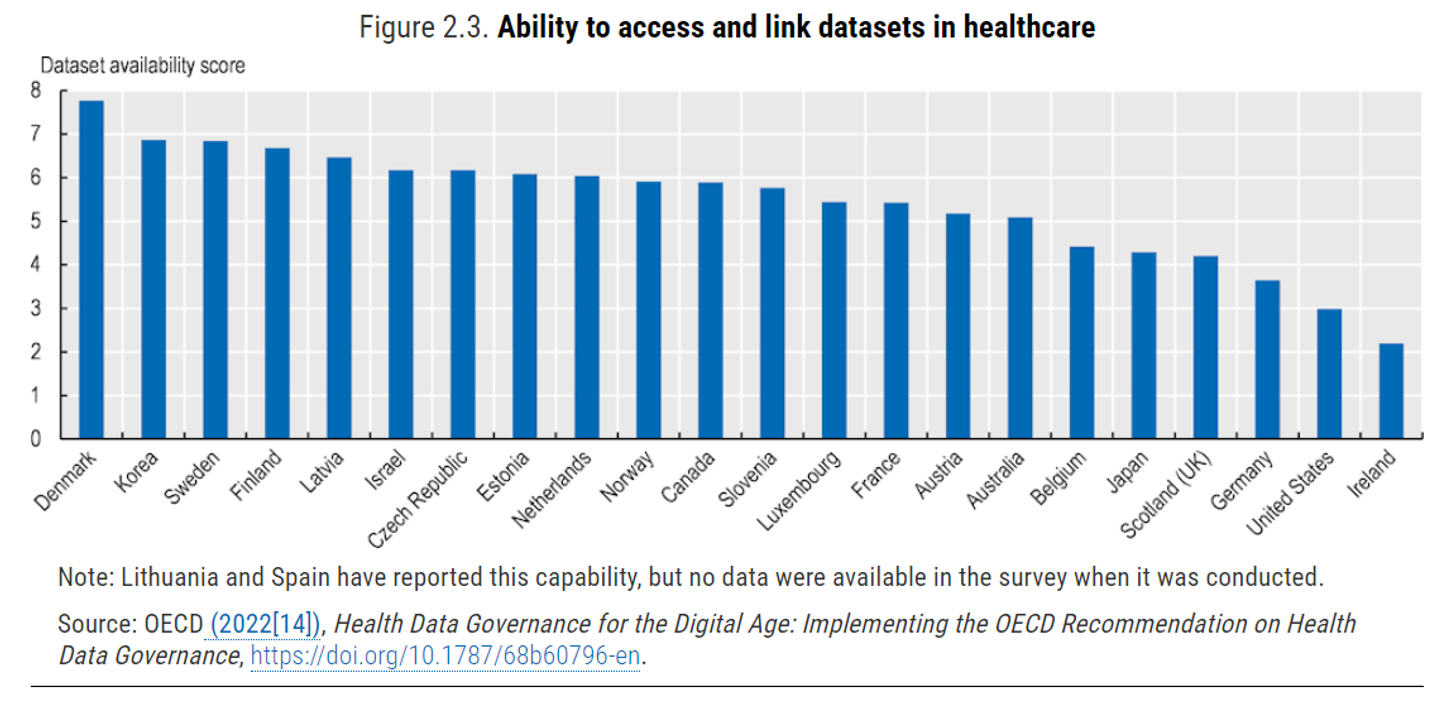

The bar chart arrays OECD’s assessment of interoperability gauged in 2022, with Denmark, Korea, Sweden, Finland, and Latvia in the top 5 for data linking; and, Ireland, the U.S., and Germany ranking in the bottom three.

In health care, we have a plethora of standards for linking health information from disparate data sets. These “support the exchange of data between technologies while the content of data is protected,” the OECD explains in the chapter. |Semantic and technical standards work together, so local physical data standards are connected to each other while maintaining data quality and integrity.”

OECD found that over 90% of the countries studied reported introducing legislation to require standards for interoperability, and (wonk-alert) with two-thirds adopting HL7-FHIR, and 42% adopting SMART on FHIR. The latter standards are helping to simplify data queries, access, and exchange between systems, supporting the development of APIs (application programming interfaces) which help to “appify” electronic health records and other traditionally ill-liquid platforms.

Here, the U.S. is found to be lagging other nations. With the HITECH Act’s financial support enabling hospitals and physicians to purchase and implement EHRs, interoperability was not baked into the plans and processes from the start. In other countries with fewer payors and health plan sponsors, and more uniform or universal health care financing and provision of services, we have seen more coordination and planning for interoperability — such as the role model health IT ecosystem in Denmark.

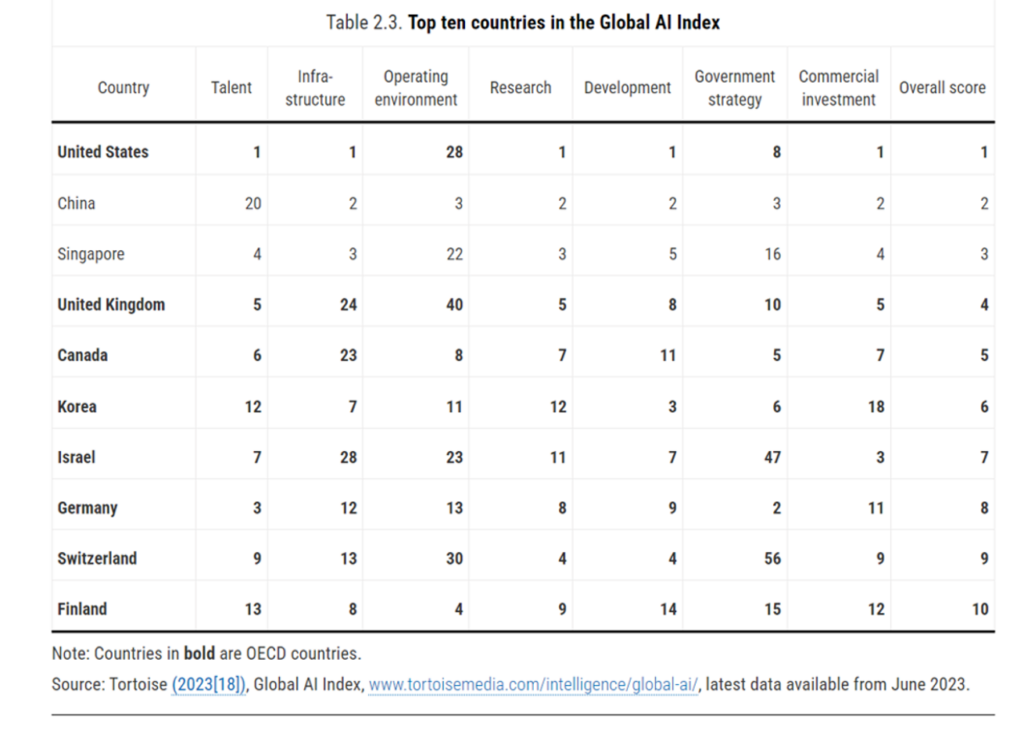

So with the U.S. ranking near-bottom for interoperability, America ranks top for AI in the OECD’s Global AI Index. This scoring is based on the Index using data from June 2023, as prepared by Tortoise Media.

In this analysis, the U.S. leads in five of the seven dimensions evaluated: talent, infrastructure, research, development, and commercial investment.

The OECD points out that AI will surely be an area of “significant interest” in health care — with the EU (via the proposed Artificial Intelligence Act), Canada (with the proposed Artificial Intelligence and Data Act), and the US (via the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights) already proposing regulation of the technology.

The OECD calls out a critical area to address in the rollout of AI across health systems: social acceptance, noting studies in the U.S. that have found patients want doctors to be “the face of care” and don’t favor being diagnosed “by a machine,” per 2023 research from the Pew Research Center.

Those are just two of a dozen key lenses on digital health innovation in developed countries the OECD discusses in this always-informative report. If you are involved in digital innovation, even within a single country, there are lessons to learn in here based on others’ experiences, successes, and stumbles.

As OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann notes in the report’s press release, digital health transformation is key to public and individual health, and to economic development: “Timely and affordable access to high quality health care is an economic as well as a social imperative, as it enables people to participate fully in our societies, boosting labour force participation and worker productivity.”

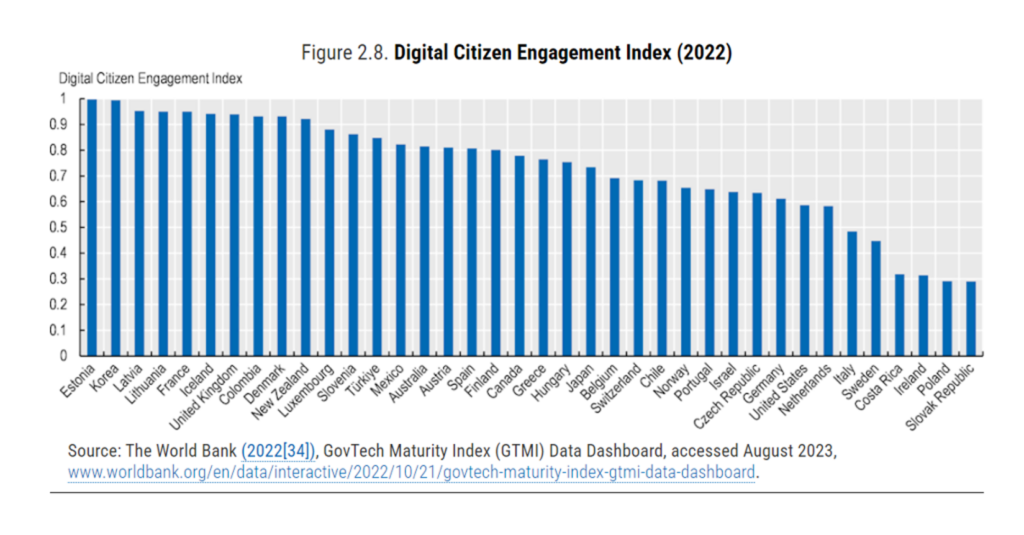

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Let me conclude with this comparison of countries’ “digital citizen engagement.”

“People being at the centre {of health/care} means more than ensuring that people have access to their EHRs; it also means ensuring that people are meaningfully engaged in the design, implementation, operation, and management of digital health programmes,”

the report asserts.

Digital Citizen Engagement translates into,

- Allowing citizens and businesses to provide anonymous feedback

- Responding to citizen feedback

- Making government responses publicly available

- Using advanced technology to improve citizen engagement (say, via chatbots)

- Establishing service delivery performance metrics

- Publishing government engagement results, and,

- Improving the representation of vulnerable groups.

Digital health is a determinant of health, the OECD writes in this chapter, noting the importance of health citizens’ digital connections to access health care, education, and to source the essential basic needs of everyday living.

My own take on this in my book Health Citizenship embedded digital citizenship as one of four pillars of overall health citizenship — along with healthcare as a civil right (“a health plan in every pot”), trust, and a new social contract of “love” to bolster public health and healthy communities.

“Countries are ‘data rich and insights poor,'” the OECD chapter on digital health at a glance concludes. In the U.S., we are in the early AI adoption phase “rich,” but we are “interoperably” poor. Getting the latter aligned while ensuring trust-by-design, equity-by-design, and privacy-by-design for the former will help us get closer to health citizenship in the U.S. — and truly insights-rich for all.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...