“Clinical transformation with AI is easier without patients.”

When Dr. Grace Cordovano heard this statement on a panel of physicians convening to share perspectives on the future of AI in health care held in early March 2024, the board-certified patient advocate felt, in her words, “insulted on behalf of the patient communities I know that are working tirelessly to advance AI that works for them.”

“The healthcare ecosystem and policy landscape must formally recognize patients as end-users and co-creators of AI,” Cordovano wrote to me in an e-mail exchange. “Patients, their care partners, caregivers, and advocates are already utilizing AI powered tools and creating their own LLMs in ways that the average physician, healthcare executive, and health IT vendors would not believe. We are lighting our own ways because we know no one is coming to save us, especially when we are facing our or our loved one’s mortality. AI can give us the competitive advantage against our diagnoses and the healthcare system, where the odds are consistently stacked against us.” Cordovano further explained to me.

“Generative AI can either deepen and restore trust or exacerbate mistrust and introduce new skepticism among consumers and health care stakeholders alike,” Deloitte explained in a report on the emergence of GenAI in health care.

Move fast with AI and break things? Not so fast, consumers say

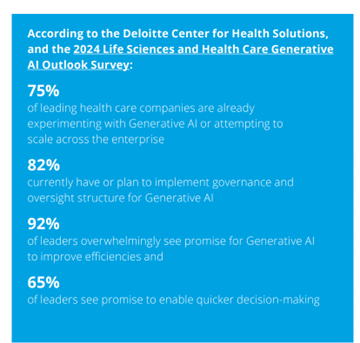

In its introduction to the company’s Tech Trends 2024 report, Deloitte called GenAI, a “force multiplier for human ambitions.” That is certainly the case for health care’s ambitions, Deloitte noting that 75% of health care companies were already piloting GenAI.

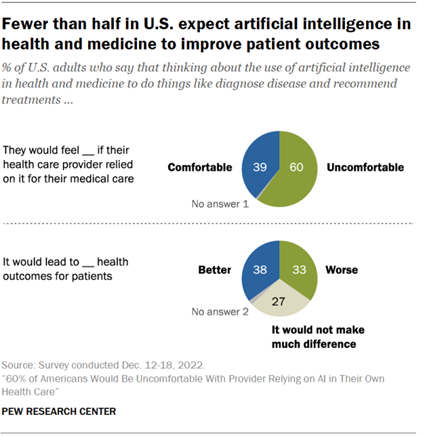

Although most health care organizations and company leaders view the adoption of AI as promising, most Americans are concerned providers will adopt AI technologies too quickly rather than too slowly. Three in five U.S. adults would be uncomfortable if their health care provider relied on AI for their medical care, according to the Pew Research Group. The other side of that coin is that only 2 in 5 people thought AI would lead to better patient outcomes.

There are other aspects of AI applied to health care about which U.S. consumers are concerned: especially AI’s potential impact on a patient’s personal relationship with their health care provider, and assuring the security of personal health records, Pew also learned.

Furthermore, women’s trust in deploying AI for health care services ranks lower than men’s: 66% of women would be uncomfortable if their provider relied on artificial intelligence, compared with 54% of men.

Declining trust in U.S. health care overall impacts trust in the AI-health layer

This AI/trust lens overlaps Americans falling faith in the American health care system in a compounding way.

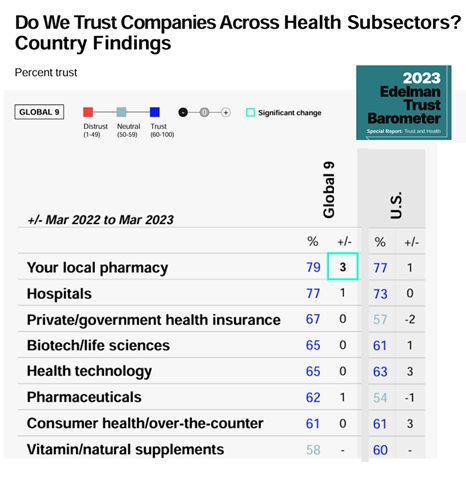

While the health care industry in general commands a somewhat higher level of trust among Americans than some other sectors do, there is variation in trust-equity across various segments of the U.S. health care ecosystem.

The 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer gauged U.S. adults’ levels of trust in health care services and suppliers, finding the greatest trust lies with a consumer’s local pharmacy (for 77% of consumers), followed by hospitals (for 73% of people) and in third rank, health technology (63%).

Layered on top of this is health citizens’ eroding trust in other aspects of U.S. public health, as well. Most striking in the Edelman 2023 research was the finding that more consumers trusted peer voices – friends and family – on par with medical experts, and well above the advice of national health authorities and global health authorities.

How to take a “patient-first” approach with GenAI – learning from the World Economic Forum

At the annual conference of the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2024, WEF heavily focused in on AI and its implications and prospects for society and many vertical markets, including health care.

As part of these discussions, WEF published a report on Patient-first health with generative AI with the subtitle, “reshaping the care experience.”

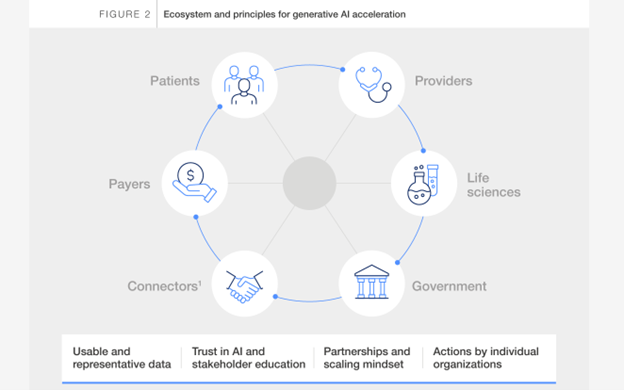

“Encouraging generative AI adoption in healthcare depends on instilling models with empathy and domain-specific knowledge, mitigating bias by connecting the data ecosystem and continuously fine-tuning models, keeping humans in the loop and developing more cost-effective ways to train and run multi-modal foundation models,” the paper recommended.

WEF identified three areas of opportunity for patient-first GenAI in health care, addressing:

- Health education assistance and lifestyle support, designed for consumers and caregivers;

- Co-pilots for patient triage, the “first-mile” to help understand where to direct patients for diagnosis or treatment; and,

- Disease management interventions for monitoring, side effect management, and adherence keeping patients on recommended treatment paths.

But how to bake in “patient-first-ness?” The WEF’s research revealed several success factors,

First, to build trust through empathy and interactivity – with clinicians reviewing responses coming out of the AI to improve the output-results.

Second, to keep humans in the loop, educating patients and providers on GenAI’s limitations such as the potential for hallucinations. On a parallel track, integrate patient-facing tools into clinical workflows and risk-management high-risk discussions with patients dealing with “severe disease.”

Third, to scale across what WEF terms “contexts” – appreciating and recognizing peoples’ unique needs. The point: that one size does not fit all people or situations and requires a user-centered design approach.

Fourth, to mitigate against potential bias across the data and stakeholders (providers, payers, public sector/government, and pharma) making sure to include data from under-served populations.

Including the algorithmically underserved

Dr. John Halamka, President of the Mayo Clinic Platform, raised this last point two years ago at the HLTH 2022 conference, talking about the “algorithmically underserved.”

Simply put, this is the population of people who are not well-represented in health data sets for three reasons Dr. Halamka and fellow researchers shared on the MCP website: people whose data is not available in electronic form, often patients who lack a primary care provider or clinician without an EHR; people whose data are electronic but in sample sizes too small to yield good results from the algorithm – that is, when the “math doesn’t work;”; and/or, people whose data are electronic and in sufficient cohort numbers, with algorithms that do not perform well due to a particular patient characteristic. Halamka and team point out a JAMA study which overestimated the risk of heart disease in people who had high BMIs.

A recent study in Nature Medicine assessed underdiagnosis bias of AI algorithms looking at chest X-rays in under-served patient groups – identifying female patients, Black patients, and patients of lower socioeconomic status with a greater risk of biased “math.”

CHAI and TRAIN coalesce groups to promote “responsible AI”

To address patients’, consumers’ and caregivers’ concerns about AI, organizations are aiming to support “responsible AI” in health care: CHAI and TRAIN are the acronyms for these groups with similar missions and membership rolls.

CHAI stands for the Coalition for Health AI, and by March 2024 had over 1,300 representatives from across the industry. Founding members included Change Healthcare, Duke AI Health, Google, Johns Hopkins University, Mayo Clinic, Microsoft, MITRE, Stanford Medicine, UC Berkeley, UC San Francisco among others, and several public sector offices deemed “observers” such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONCHIT).

Dr. Halamka is President of CHAI, and Dr. Brian Anderson was appointed the CEO this month following many years of leadership in responsible AI work. In an interview with Healthcare IT News, Dr. Anderson asserted that, “We have this great promise of AI: that it’s going to enable people that traditionally don’t have easy access to healthcare to be able to have access to patient navigator tools. To be able to have an advocate that, as an example, might be able to go around helping you navigate and interact with providers, advocating for your priorities, your health, your needs.”

Coinciding with the HIMSS 2024 conference this week, the launch of the Trustworthy & Responsible AI Network (TRAIN) was announced. Members at launch included Advent Health, Advocate Health, Boston Children’s Hospital, Cleveland Clinic, Duke Health, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Mass General Brigham, MedStar Health, Mercy, Mount Sinai Health System, Northwestern Medicine, Providence, Sharp HealthCare, University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and Microsoft as, in the words of the press release, “the technology enabling partner.” Among TRAIN’s goals are to share best practices related to AI in health care especially focused on safety, reliability and monitoring AI algorithms, providing tools to help measure outcomes associated with the AI deployments, and to facilitate the development of a federated national AI outcomes registry to capture real-world outcomes.

To address inclusive AI and help deal with the algorithmic under-served challenge, TRAIN is also collaborating with OCHIN, which partners with community health centers and supports the largest collection of community health data in the U.S.; and, TruBridge, which partners with providers to connect patients (and their data) in rural areas with the health system.

Patients and doctors on the same page with ambient listening

One area where patients and clinicians are finding mutual satisfaction with AI is for clinical notetaking – applying “ambient listening” in the exam room to capture clinician notes in real time.

What’s held up data liquidity and interoperability, and contributed to clinician burnout and administrative burden, has been the implementation of electronic health records poorly designed for relationship-building and shared decision making.

Enter Microsoft Copilot collaborating with Epic, the largest EHR supplier, and provider organizations that have adopted Epic. A secret in this sauce has been Microsoft’s acquisition of Nuance, the voice-technology/speech recognition innovator that can be embedded into EHRs. At least 150 health systems are using Nuance DAX Copilot as an AI-based clinical scribe technology with their Epic systems.

Microsoft announced the company’s expansion of AI in health care in early March 2024, noting their study with IDC found that 79% of health care organizations reported using AI technology – with an ROI on those AI investments within 14 months, of $3.20 for every $1 invested.

Stanford Medicine clinicians deploying DAX Copilot have been tracking the outcome of using conversational, ambient and GenAI. The vast majority (96%) of those Stanford Health Care clinicians using DAX Copilot said that the technology was easy to use, and 78% said it “expedited” clinical note-taking – with two-thirds reporting DAX Copilot saving time.

A copilot for health equity

Mary Stutts, CEO of the Healthcare Businesswomen’s Association (HBA), spoke at South-by-Southwest 2024 this month on a panel brainstorming AI’s role in health care. When asked what most excited her about AI in health care, Mary quickly responded – “health equity: not just the impact on peoples’ needs and well-being but the business and financial imperative that holds back economies around the world.”

Prior to joining HBA, Mary worked earlier in her career with Stanford Health Care. As Chief Health Equity and Inclusion Office, Mary led DEI initiatives and had occasion to collaborate with Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI. Mary was advocating for the role that AI could play to mitigate physician bias that could impede care for patients. In 2019 they conducted a pilot at Stanford in exam rooms that employed ambient listening into physician and patient conversations.

The pilot, which is now part of Stanford Medicine’s workflow, was building on helping streamline physician workload but also has the potential to impact evidence from previous studies learning that some doctors did not listen well in all patient discussions, especially for those involving women and people of color. (For more on the challenge of gender, check out this recent analysis of 1.8 million medical records).

The Stanford pilot found that the AI technology captured the conversations (via digital scribing) generating notes and options that the AI identifies such as possible clinical trials and new therapies that, once complete, were put into the patient’s electronic health record. “We educate patients to advocate for themselves,” Mary explained at SXSW, “but this helps people understand why we recommend they regularly ask for a copy of their medical record – empowering patients to learn whether they are eligible for a clinical trial, learn about innovative therapies, or access other care opportunities that may not have been communicated to them before.

Onward to patient inclusion in AI: #PatientsUseAI

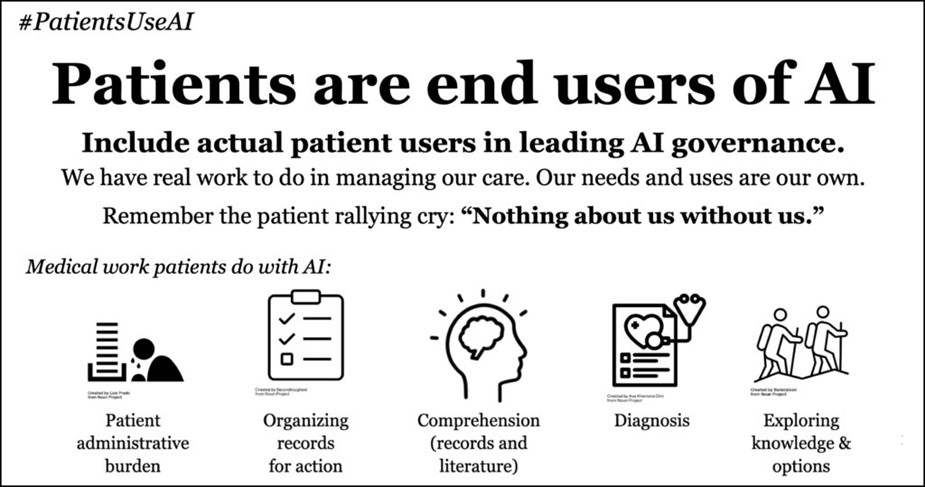

In the meantime, while the health IT industry and health care providers are organizing to share best practices and responsible AI protocols, patients at the vanguard of advocacy and peer-to-peer health care are also leading their charge toward further patient and caregiver empowerment and engagement with AI. Cordovano partnered with “ePatient” Dave DeBronkart to create and promote a hashtag, #PatientsUseAI, as a social media rallying call-to-action for AI: Patients Included.

The graphic illustrates five areas where patients are already using AI to do “medical work,” including helping deal with patient administrative burden (such as bill organization and provider navigation), organizing medical records, understanding their records and the medical literature, diagnosis, and researching options for treatment.

In January 2024, the World Health Organization published guidance for AI ethics and governance to advise health care providers, governments, and technology companies as they design and deploy large language models for health care services and research. Among their recommendations was to engage the public to understand data sharing, to assess social and cultural acceptability, to improve AI literacy, and to apply consumer protection laws and lenses to present negative impacts on end-users and patients.

As we continue to imagine, build-out, and implement AI in health care, being inclusive and responsible should also mean bringing all patients’ voices and data into the algorithmic models, research, and settings so that no one’s care is delayed or under-diagnosed.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors.

Interviewed live on BNN Bloomberg (Canada) on the market for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and their impact on both the health care system and consumer goods and services -- notably, food, nutrition, retail health, gyms, and other sectors. Thank you, Feedspot, for

Thank you, Feedspot, for  As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...

As you may know, I have been splitting work- and living-time between the U.S. and the E.U., most recently living in and working from Brussels. In the month of September 2024, I'll be splitting time between London and other parts of the U.K., and Italy where I'll be working with clients on consumer health, self-care and home care focused on food-as-medicine, digital health, business and scenario planning for the future...